The red wave of Republican victories many expected in the 2022 midterm elections never materialized, but the election results still suggest that American democracy is facing a significant, enduring challenge. Given that many election deniers ran for offices that would include some degree of control over elections, it would have made sense for democracy to be a key campaign issue. Yet few campaigns focused on how the 2022 election might affect the health of our democracy.

Although several prominent election deniers lost their races, a few succeeded, and the election results contained other indications of threats to the democratic political system. Many Members of Congress who voted not to certify the results of the 2020 election kept their offices, and two attendees of the Jan. 6 rally that led to the riot won election. And because the Republicans won a majority of seats in the House, congressional investigations into Trump’s involvement in Jan. 6 will likely come to an end.

The American public has always had a complicated relationship to democratic norms. Research finds that the public expresses a strong commitment to democratic norms in the abstract but fails to apply these norms consistently in practice. Two trends help explain why citizens may not provide a bulwark against anti-democratic politicians and practices. First, data shows that partisanship makes attachment to leaders and loyalty to particular groups a primary consideration for many voters. Second, a substantial number of Americans say they believe the country needs a leader willing to violate some of the rules and norms of democratic society.

Partisanship

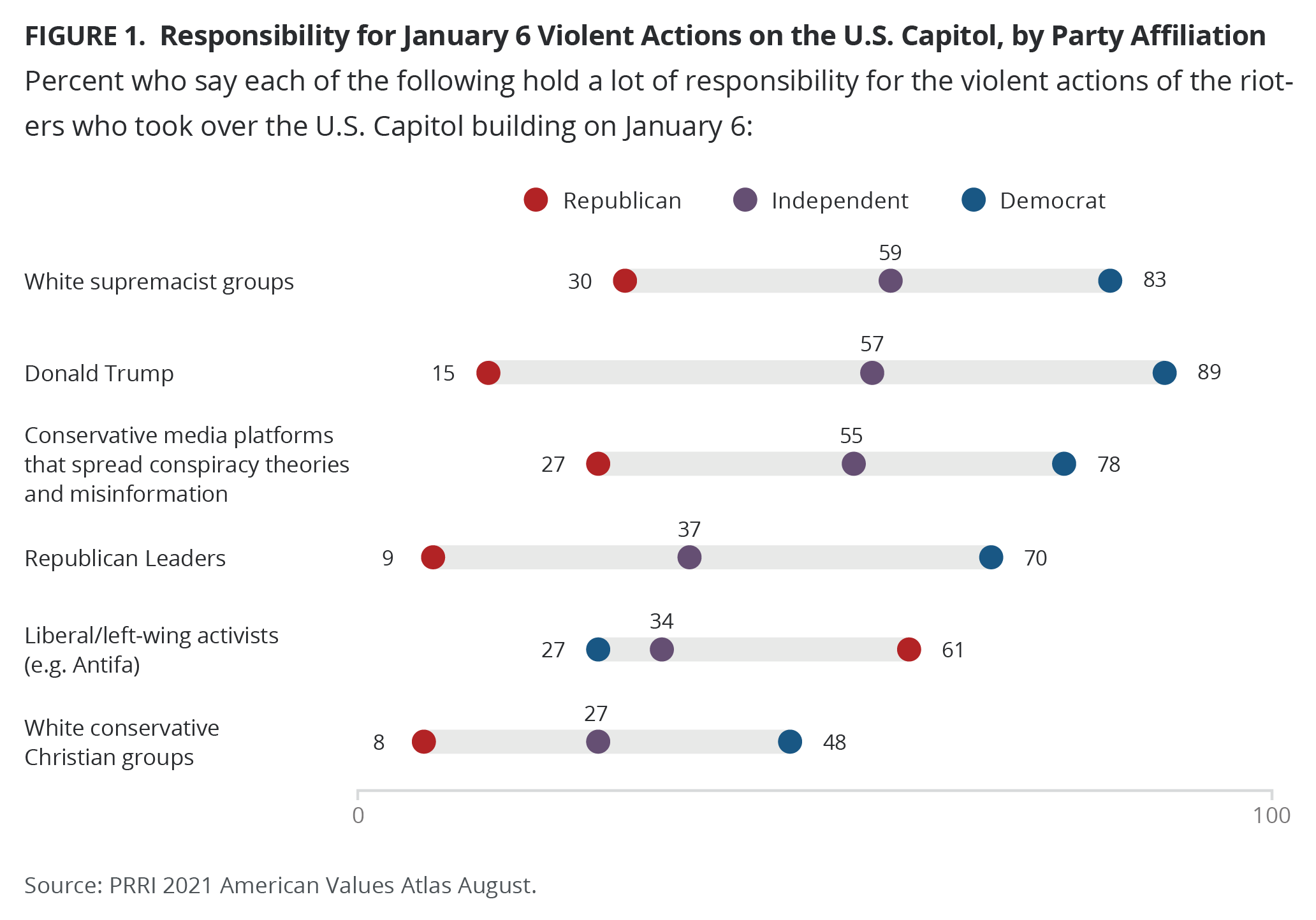

In an era of polarization, people are less willing to stray from their partisan group or to challenge their co-partisans and hold them accountable. Citizens are also less likely to want to punish political leaders who have engaged in misconduct or corruption when those leaders are part of their own party. This may help explain why Republicans are more likely to excuse Donald Trump for wrongdoing in the Jan. 6 riots. In an August 2021 survey, PRRI asked voters about the insurrection. Only 15% of Republicans said they believe Donald Trump bears a lot of responsibility for the violence on Jan. 6. This stands in stark contrast to the 57% of independents and the 89% of Democrats who believe Trump is responsible. At the same time, 61% of Republicans said they believe left-wing groups are responsible for the violence, though there is no evidence to suggest that this is true.

When partisans believe their identity is threatened, they are more likely to purposefully harm other members of their partisan outgroup. And, perhaps most importantly, strong partisans are more willing to support politicians who make promises at odds with democratic principles if those politicians belong to their party.

Support for Strongman Leaders

The populist wave that has bolstered the far right in many established democracies over the past ten years has shaped attitudes within the United States as well. When people feel a sense of threat, they focus on security and may see trading democratic freedoms to feel protected as the best pathway forward.

My research (with colleagues Andrew Bloeser, Candaisy Crawford, and Brian Harward) investigates why some people avoid messy political processes. Previously, scholars argued that the desire for so-called stealth democracy (that is, a democracy that functions without citizens having to be aware of or participate in it) reflects a general desire to avoid conflict and disagreement. But our work identifies another explanation. We find that many people who do not want to see or participate in politics are interested in leaders who they believe will protect them and punish their enemies. Many of these people are not simply avoiding the messy “sausage-making” process of legislation. Instead, they are not committed to the democratic process itself. The fact that some individuals are prepared to roll back democratic norms and support leaders who focus on attacking outgroups poses a challenge to democracy and an opportunity for potential demagogues.

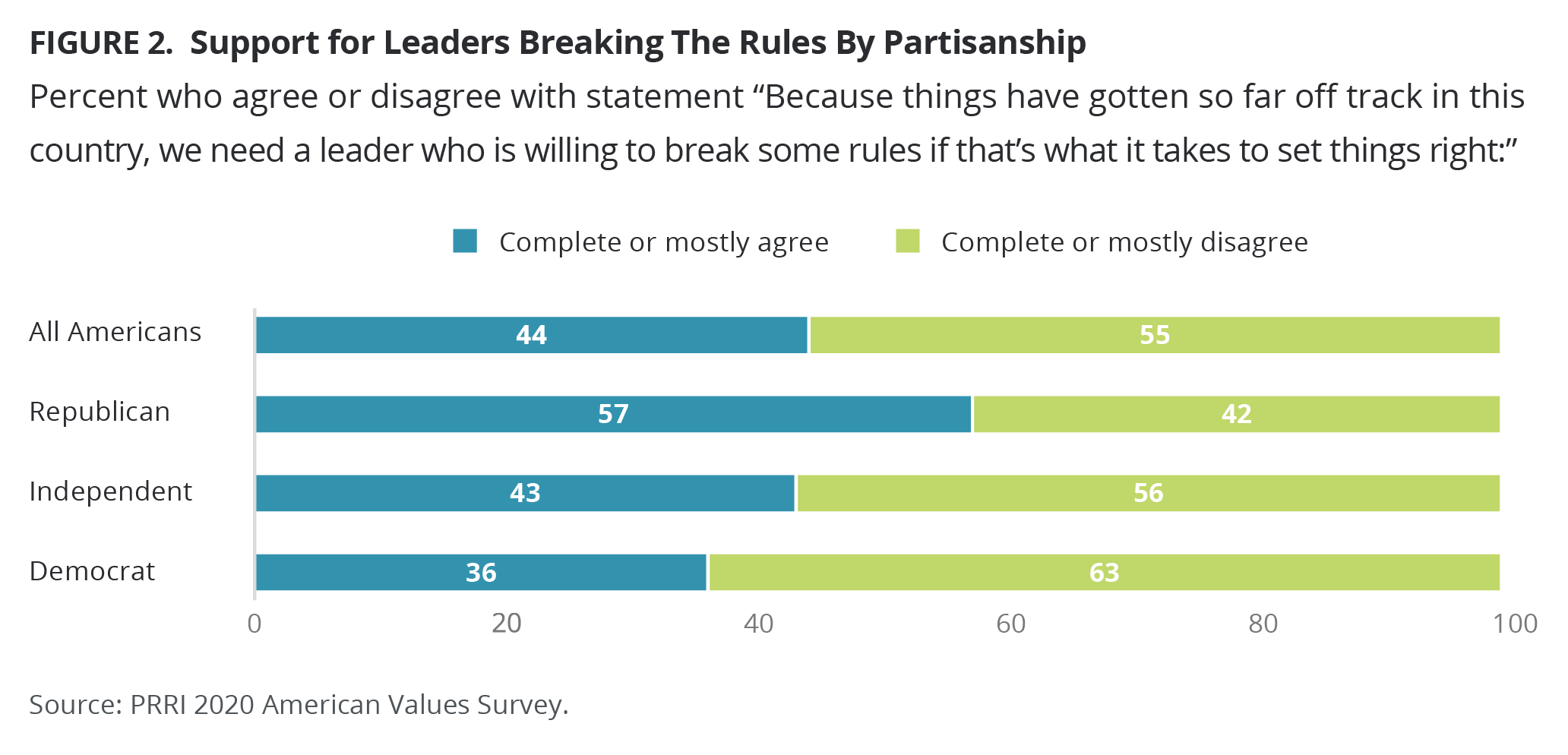

Other evidence points to a similar conclusion. PRRI has asked survey respondents to weigh in on a question about leaders breaking the rules five times since April 2016. Respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement “Because things have gotten so far off track in this country, we need a leader who is willing to break some rules if that’s what it takes to set things right.” Each of the five times this question has been asked, between 43% and 49% of respondents have mostly or completely agreed with the statement. While this overall pattern has been consistent between 2016 and 2020, there are interesting differences among partisan groups. For instance, the partisan breakdown in 2020 shows there are substantial minorities and some majorities who favor rule-breaking leadership. Support for rule breaking is highest among Republican-identifiers, followed closely by independents. A majority of Republicans (57%), and even more than a third of Democrats (36%), agree that we could use a leader who will break some rules. While a majority of the public opposes these rule-breaking leaders, the appetite for these types of leaders among some groups poses an ongoing problem for democratic governance.

Although this survey question cannot tell us exactly what kind of rule-breaking people may support, the responses indicate that the desire for ingroup protection means that it could have very damaging democratic consequences.

In November, much of the post-election chatter focused on Donald Trump losing his grip on the Republican Party, even as he announced his 2024 presidential run. But these findings suggest that a weakened commitment to democracy is not the result of one leader. Instead, it is a force among that public that can create a permissive atmosphere for politicians.