Drs. Youssef Chouhoud, Dara Delgado, and Seth Gaiters were 2024-2025 PRRI Public Fellows studying the intersection of politics, religion, and religious and ethnic pluralism. This Spotlight Analysis details the findings of their original, collaborative research conducted with support from PRRI.

In Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together? And Other Conversations About Race, Beverly Daniel Tatum examines why high school-aged people are often found in social spaces with those who share their racial identity, despite the mixed racial makeup of their learning environment. Tatum asks whether this tendency to self-segregate is a problem to be solved or a coping mechanism for navigating racial dynamics. The universal appeal of Tatum’s work confirms that while racial identities are not essential, recognizing their influence remains critical to understanding Americans’ collective inability to communicate across racial and ethnic divides. Applying this lens to church contexts raises a related question: Beyond personal affinities such as style of worship, preaching, and programming, what other factors contribute to where and with whom Christian Black Americans choose to worship?

This Spotlight examines whether a congregation’s racial and ethnic makeup influences the salience of religious identity and, in turn, aspirations for socioeconomic mobility. Specifically, we explore how class, status, and station influence religious self-expression and congregational participation, and whether higher socioeconomic status helps minorities to overcome racial biases in predominantly white congregations. Our research suggests that when choosing a congregation, Black Christians weigh factors such as denomination, location, socioeconomic status, and political stances of senior leaders as expressed in their sermons, reflecting a mix of strategic, social, and cultural considerations. The strong preference for predominantly Black congregations may indicate a desire for safety and solidarity, but the data also highlight that factors such as denomination and class composition shape decisions as well. As a result, many continue to opt for racially homogenous faith communities at a time when they are “not bound [to] just the Black church.”

Choosing to Segregate: Black Congregational Choice

In July 2025, with support from PRRI, we conducted an online national survey of 750 Black Americans living in the United States, including both native-born and foreign-born individuals, through Qualtrics Panels. Although participants were volunteers (i.e., not a random sample), we incorporated gender, education, and age quotas to ensure that our sample was more representative of national demographic patterns.

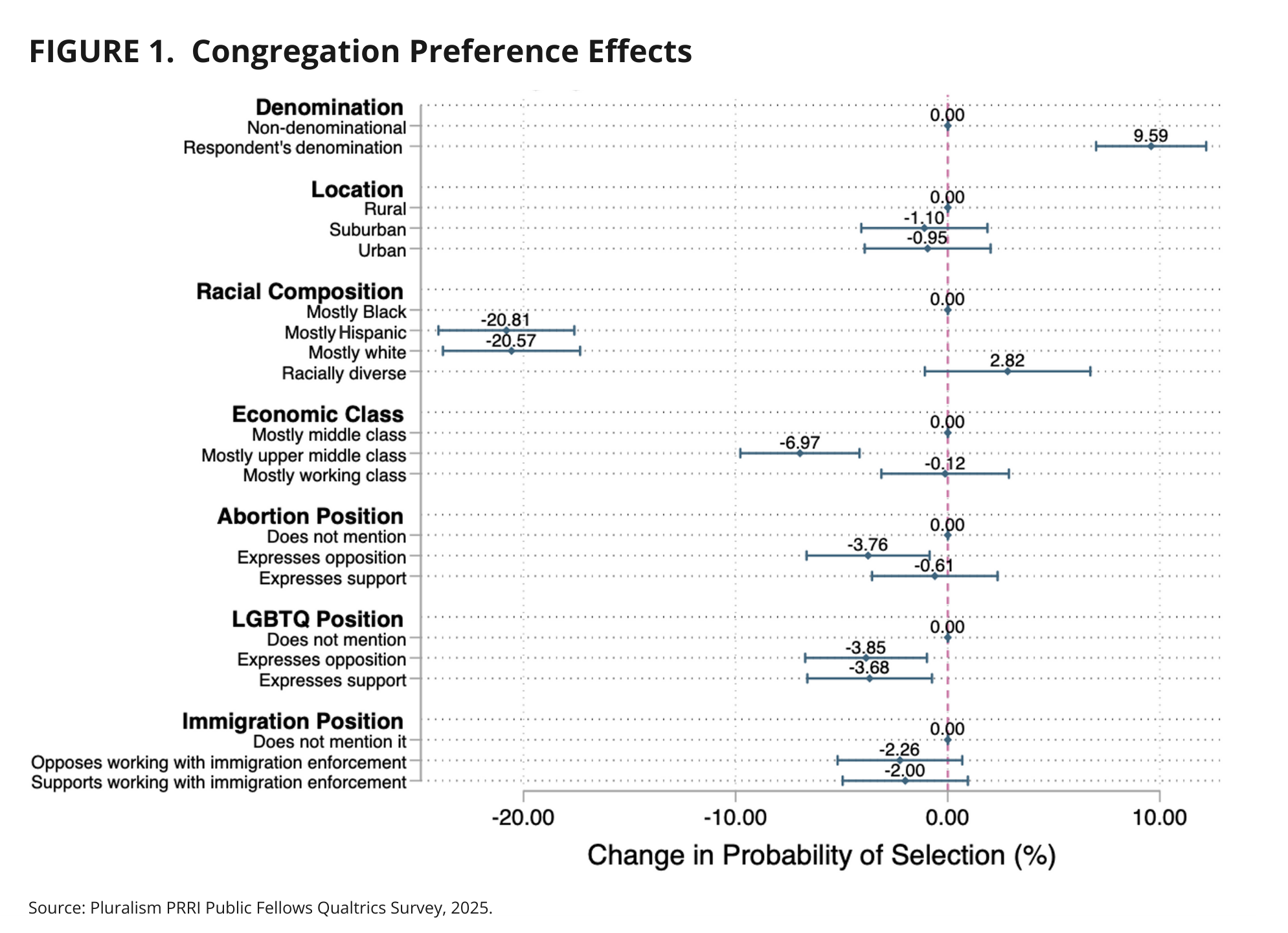

As part of this original survey, we used conjoint analysis to examine the factors Black Christians value most when choosing a religious congregation. Respondents were shown side-by-side profiles of two hypothetical congregations, each with randomly assigned characteristics like denomination, racial and economic makeup, and sermon topics (such as abortion, LGBTQ rights, and immigration). They then chose which one they would prefer to join.

Conjoint analysis is especially useful because it mimics real-world decision-making, where people consider multiple factors at once. By randomly varying each attribute across multiple pairings and respondents, researchers can isolate the effect of any single trait, such as a congregation’s racial makeup, on the likelihood of being chosen. This enables the measurement of the independent influence of each characteristic while holding all others constant.

Figure 1 shows how different traits shift the probability of a congregation being selected, relative to a reference category (e.g., “Does not mention abortion” is the reference for abortion stance). Respondents preferred congregations that matched their own denomination (+9.6%).[1] Congregations that were majority white (-20.6%) or majority Hispanic (-20.8%) were far less likely to be chosen than those that were predominantly Black.[2]

While there was no notable preference in geographic location, with near complete parity between urban, suburban, and rural options, economic class makeup did move the needle on congregation choice. Specifically, respondents were significantly less likely to choose a congregation where church members were mostly upper class (-7%), compared with those where they were mostly middle class. Lastly, except for immigration, mentions of political issues like abortion and LGBTQ rights generally tend to reduce a congregation’s appeal regardless of the position taken, perhaps suggesting many prefer churches that avoid explicitly political sermons.

This analysis indicates that among the factors tested, racial composition stands out as the most influential in shaping congregational choice. While other factors like denomination, social issue positions, and economic class composition also matter, their effects are considerably smaller — typically ranging from 2-7 percentage points. This suggests that racial composition functions as a primary filter in congregation selection, potentially overshadowing other important considerations like theological alignment or community characteristics. The magnitude of these racial preferences indicates they may serve as an initial screening mechanism, where other attributes become secondary considerations once racial composition preferences are satisfied.

So What?

According to data from the 2022 PRRI American Values Atlas, 57% of Black evangelical Christians report attending religious services regularly. However, neither PRRI’s data nor the current results of this study tell us exactly how Black Christians’ personal and political commitments align with their respective faith communities, or what specific characteristics make some congregations more attractive than others. Even so, our research suggests that when it comes to where they worship, many Black Christians continue to opt for predominantly Black churches. While the reasons are varied, this may reflect a desire to be part of an institution that affirms and reflects the Black experience in the United States, especially amid broader pressures of assimilation in schools, neighborhoods, and other social settings.

By examining Black Christians’ religious, class, and political identities, the study challenges the prevailing generalizations about class status and religious behaviors that often ignore or pejoratively categorize religious Black Americans as deviations from the dominant culture’s material, ethical, and social norms. Likewise, it offers an initial exploration into the factors that influence where Black Christians choose to sit in church on Sunday morning.

– “The Border Informs My Faith”: Oral History Methodologies and Understanding Immigration Politics Among People of Faith in Arizona

– Americans’ Responses to Abortion’s Uncertain Legal Landscape

– Faith, Freedom, and the Future of LGBTQ Rights in America

– Democracy Today: Insights on Race, Religion, and Democratic Principles

[1] Confidence intervals that cross the vertical red line in Figure 1 indicate that the observed differences are not statistically significant, while those that do not cross the line indicate statistically significant effects.

[2] Figure 1 depicts Average Marginal Component Effects (AMCE) multiplied by 100, indicating percentage change in the probability of a congregation being selected.