The racial and ethnic makeup of the United States is rapidly changing as boundaries between racial and ethnic groups are becoming unclear by a growing number of Americans who are identifying more and more as multiracial. Census estimates project the population of Americans who identify with two or more races to be the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group over the next decades. Because race and ethnicity shapes Americans’ experiences with education, employment, health, and interpersonal interactions, it is important to better understand what the general characteristics of multiracial Americans are and how their views and attitudes toward a host of issues differ from other racial and ethnic groups.

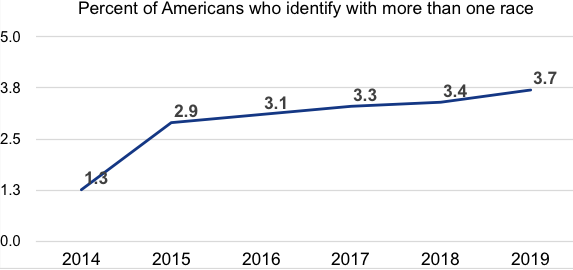

The U.S. government uses the census to determine the official racial makeup of the nation. Over the past few decades, the question of race has expanded to include many categories. For example, Hispanic/Latino origin, as well as an open-ended ancestry question, were added in 1980. In 2000, the census allowed respondents to choose multiple racial identities, and included measures of race, Hispanic origin, and ancestry (which asked respondents to fill in their “ancestry or ethnic origin.”) Even though the percentage of multiracial Americans remains fairly small, it has increased significantly over time. Nearly four percent (3.7%) of Americans identify with more than one race according to the PRRI 2019 American Values Atlas Survey, which is about three times more than Americans did in 2014 (1.3%).

Close to one-third (28%) of multiracial Americans say their racial background consists of being both black and white, according to the 2018 American Community Survey. Romantic and sexual relationships between black and white Americans have a troubled history within (but not limited to) the United States.

Before the census offered Americans the ability to identify as two or more races, multiracial Americans were presented with categories like mulatto, octoroon, and quadroon from the 1790s until the early 1900s. For the American government, blackness as a category required a type of measurement that would not allow it to go unnoticed in an individual’s perceived genetic makeup. Antebellum miscegenation laws made sexual and romantic relationships between black and white Americans illegal, yet racial categories (like mulatto, octoroon, and quadroon) were legally maintained for the children born from these unions. Anti-miscegenation laws worked to absolve white men of the violent sexual crimes they committed against black women, while simultaneously protecting the social virtue that white society assigned to white womanhood.

It was not until the 1967 Supreme Court case Loving v. Virginia struck down Antebellum anti-miscegenation laws, and in its aftermath legal interracial unions increased. In fact, in 1967 only 3% of all marriages were interracial marriages. Today, one in six marriages has a spouse of a different race or ethnic background. In 2000, the creation of new racial categories acknowledged that an American could be biracial or multiracial. Thus, it should come as no surprise that today multiracial Americans are younger than the general population. Twenty-six percent of multiracial American are between the ages of 18-29, compared to 21% of the general population. Only 13% of those who identify as more than one race are over the age of 65, compared to one-fifth (21%) of the general population.

Interestingly, the top 5 states with the highest percentages of Americans who identify as multiracial in 2019 are California (12%), Texas (6%), Florida (6%), New York (6%), and Pennsylvania (4%). Multiracial Americans are evenly split for gender (50% vs. 50%) and about two in ten (19%) hold a college degree, compared to one-third (33%) who hold a high school education and a little over three in ten (31%) who have some college. Levels of education among multiracial Americans are comparable to those of the general population and have remained stable since 2014.

Multiracial Americans are less likely than the general population to be Protestant (39% vs. 45%) or Catholic (12% vs. 20%), and more likely to be religiously unaffiliated (35% vs. 24%).

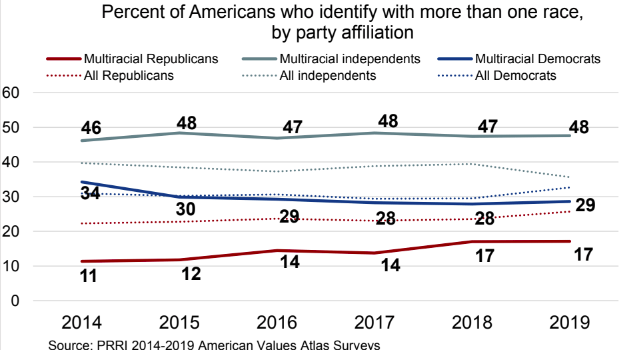

Moreover, Americans who identify with more than one race are more than twice as likely to identify as Republicans than as Democrats over the past half-decade, though the gap between Democrats and Republicans appear to narrow over time. In 2014 more than one-third (34%) of multiracial Americans identified with the Democratic party, but in 2019 this number decreased to 29%. By comparison, about one in ten (11%) multiracial Americans identified with the Democratic party in 2014, while this number increased to 17% in 2019. Nearly half of multiracial Americans identify as independents and remain stable over time (46% in 2014 and 48% in 2019).

Perhaps what is more interesting about multiracial Americans’ political affiliation is that compared to the general American population, multiracial Americans tend to be less Republican and more independent, but do not differ notably from American Democrats.

Finally, multiracial Americans are equally split in their political ideologies as nearly three out of ten (29%) identify as conservative and an equal percentage (29%) identify as liberal in 2019. Nearly one in four (36%) multiracial Americans identify as moderate. Proportions of conservative, liberal, and moderate multiracial Americans have remained stable over the years.

PRRI is adding multiracial Americans to its standard race and ethnicity categories to report when the sample size for the group is sufficient (n=100 or more) in order to highlight the unique experiences of this growing segment of the population.