With the exception of white evangelical Protestants, majorities of most religious and demographic groups believe that immigrants strengthen the United States and support having a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants who were brought to the country as children. White evangelical Protestants, however, are more likely to say that undocumented immigrants should be deported and question immigrants’ contributions to society. Much has been written about the ideological, political, and sociological forces behind the rise of nationalist, nativist, and protectionist attitudes toward immigration among white evangelical Protestants in the United States. However, there are communities within white evangelicalism that support immigrants and refugees, and these groups get much less attention.

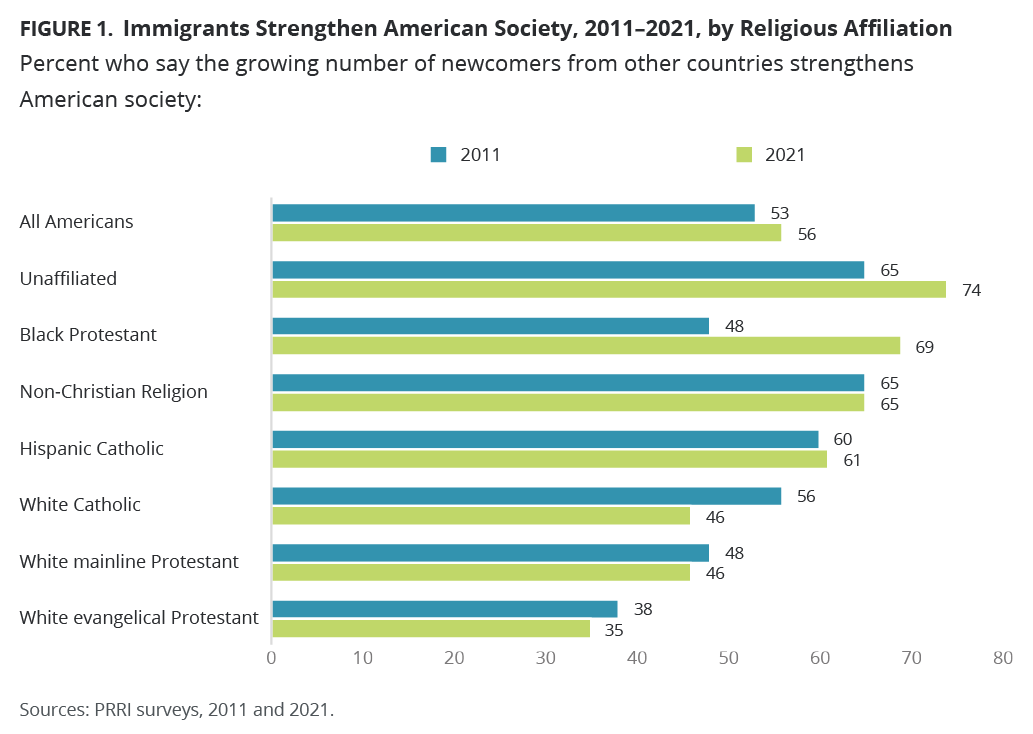

We can see the differences in attitudes among white evangelical Protestants displayed in public opinion polls, such as PRRI’s American Values Survey. The majority of people in the United States (56%) say that newcomers strengthen American society, yet only 38% of white evangelical Protestants agreed. When compared with other religious groups, white evangelical Protestants have drastically lower levels of support for immigrants.

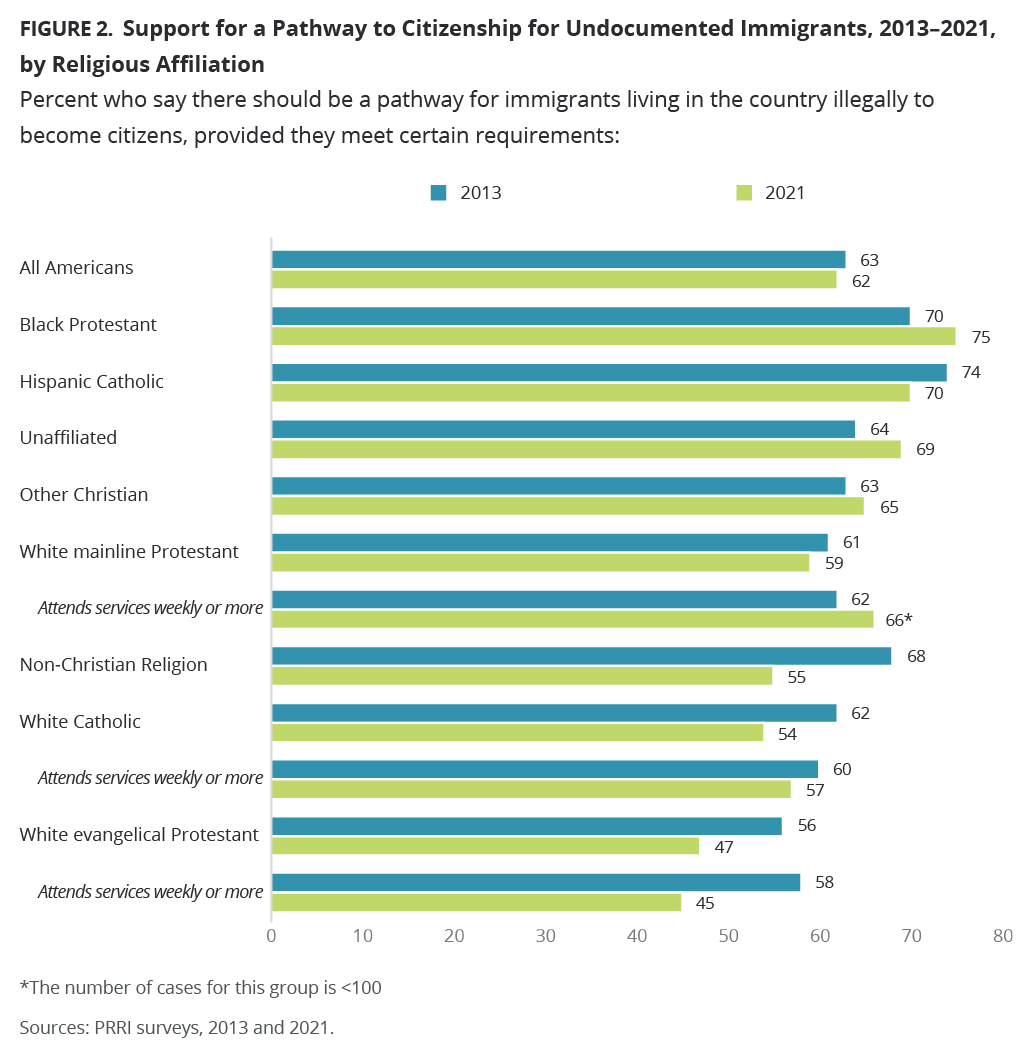

Majorities of other leading U.S. religious faiths support allowing undocumented immigrants to become citizens, but most white Evangelical Protestants do not, and their degree of support has been dropping over time. Think pieces and common narratives often point out this difference.

It can thus be surprising to find pockets of conservative Evangelicals who not only support immigration but reach out to become partners with newcomers. In March 2022, more than 40 college students and community leaders traveled to a gathering in Dallas, Texas, to learn about the experiences of refugees. The conference, titled Welcoming the Stranger, was the brainchild of Cru City and Unto, ministries of Campus Crusade for Christ International. Presenters and attendees represented evangelical Protestant organizations such as World Relief, Cru’s I.I.R. (Immigrants, Internationals, and Refugees), and the Evangelical Immigration Table. Students attended sessions that covered topics such as a theology of advocacy for immigrants and refugees, trauma-informed care, and “God’s heart for the foreigner.” In the afternoons, they met with Afghan refugees to assist with language study and document preparation or played soccer with refugee children. Given that white evangelical Protestants are not known for pro-refugee beliefs in general, what would draw these students to spend their spring break this way?

One of the most influential concepts to emerge from the political science and sociology literature of the past several decades is the idea of bridging and bonding social capital. “Bonding social capital” refers to the network ties, relationships of trust and reciprocity, and mutual obligations that exist between people who are similar in socially significant ways, often along lines of social class, race, religion, and political or social beliefs. Bonding social capital usually forms in tight-knit, homogenous groups and is accompanied by strong expectations of mutuality, trust, and reciprocity. Our sense of personal identity and our values are formed through our bonding social capital. At its best, bonding social capital creates communities of support and fellow feeling, but it can also rely on exclusionary practices, strongly enforced social boundaries, and an “othering” of those outside of the group in order to bolster the in-group identity.

“Bridging social capital” refers to network ties between people who are distinct in socially significant ways. Where race, religion, and social class divisions are significant, those who cross those lines to form acquaintances and friendships are engaging in bridging social capital. Bridging social capital can rely on a sense of co-aligned priorities or on meta identities that supersede more surface level distinctions. For instance, an identity as an American might surpass the identity of being an Easterner or Southerner, Black or white, first generation or the descendent of early Pilgrims. It brings together new ways of thinking and can foment creative, subversive ideas.

Strong societies incorporate both bridging and bonding social capital: They have networks of people who are similar and networks that are diverse; they offer communities that ground us and opportunities that pull us outward. One way of understanding the dramatically low support for immigrants among white Evangelicals is to see it as a case of a community overemphasizing bonds and lacking bridges. This is in line with research that shows a confluence of nativist, protectionist political and social positions with conservative, white evangelical religious groups.

The idea of bridging social capital can help us understand the broader context of support for refugees and immigrants among several participants of the Welcoming the Stranger conference. Some recognized a shared Christian heritage with many immigrants and refugees. Others had military experience in Afghanistan and felt a desire to support refugees who had to flee their homeland because they had a connection to the U.S. military. Still others believed that providing friendship and comfort would help make the new arrivals more open to hearing the gospel and more receptive to the Christian faith. One leader said, “for so long, we have had to go out to the nations to find people [to fulfill Jesus’ Great Commission to “go and make disciples of all nations,” as it says in Matthew 28]. Now they are coming here.” (Personal communication, May 2022). Whatever the motivation, these pro-immigrant perspectives are threads that can be woven together to create bridging social capital, leading to the integration of towns and cities, helping new arrivals integrate, and contributing to a greater awareness of immigrants’ experiences.