The enthusiastic reaction many Catholics have had to the election of Pope Francis has overwhelmed many observers of religion. Every one of his public actions and statements suggests fresh air coming out of and into the Vatican. Catholics are right to being asking “what if” questions about the Church’s future now that it clearly is under new management. For example, might Francis be open to expanding the priesthood to members of previously excluded groups, including women?

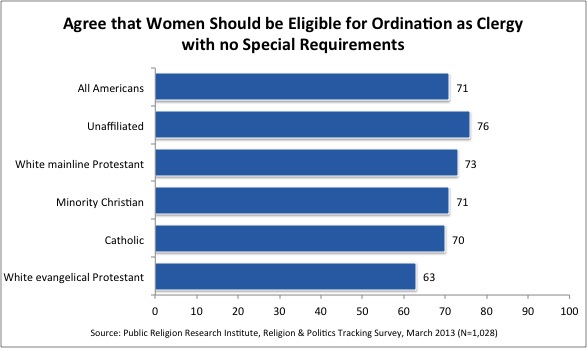

Such a development would be met with support among a majority of American Catholic laity. PRRI’s latest study shows that 70 percent of American Catholics support the ordination of women. Like most traditionalist laity, however, Catholic religious leaders are less enthusiastic about potential change to a policy that has more or less been enforced for two millennia. If gender equality is to proceed in the context of the Catholic Church, a bold, visionary pope with plenty of political capital to spend must be the one to drive it. Whether Francis is that person remains to be seen. (His record seems to indicate that he may be more favorably disposed to married priests than to women priests.)

Perhaps an even more remarkable finding in the recent PRRI study is widespread—and unprecedented—acceptance of women’s ordination among white evangelical Protestants, who typically belong to denominations or congregations that, like the Catholic Church, deny women the right of ordination. That nearly two in every three white evangelicals (63 percent) now agree that women should be eligible for ordination is extraordinary. And the path to women’s ordination in evangelical Protestant circles would depend much less on the pronouncements of one leader or executive body. Of course some large denominations would proceed slowly (if at all) toward gender equality in the pulpit. In nondenominational churches, however, it is enough for the congregation to accept a woman as its leader. Already there are small numbers of clergywomen serving evangelical Protestant churches, particularly in Pentecostal contexts such as the Assemblies of God.

Evangelicals who do not wish women to be ordained cite scripture, including 1 Timothy 2:11-12 (“Let a woman learn in silence with all submissiveness. I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over men; she is to keep silent”), to justify their stance. As in the Catholic Church, hesitancy to ordain evangelical clergywomen also is steeped in a desire to maintain tradition, which would include patriarchal gender roles. Much more than their Catholic counterparts, however, many conservative evangelicals define their very identity through their strong opposition to shifting societal norms, including gender equality.

Evangelicals who do not wish women to be ordained cite scripture, including 1 Timothy 2:11-12 (“Let a woman learn in silence with all submissiveness. I permit no woman to teach or to have authority over men; she is to keep silent”), to justify their stance. As in the Catholic Church, hesitancy to ordain evangelical clergywomen also is steeped in a desire to maintain tradition, which would include patriarchal gender roles. Much more than their Catholic counterparts, however, many conservative evangelicals define their very identity through their strong opposition to shifting societal norms, including gender equality.

What, then, accounts for PRRI’s finding that a sizable proportion of white evangelical Protestants—nearly as large as the proportion of Catholics who share the same view—now supports the ordination of women? A leading hypothesis is that younger evangelicals are driving growing acceptance of women as pastors. After all, younger evangelicals have taken stands at odds with many of evangelical Protestantism’s longstanding positions on socio-moral issues, such as gay rights and climate change. Are these young evangelicals the leading edge of sweeping transformation within the U.S.’s largest religious tradition? In short, no, at least on the question of women’s ordination. We analyzed support for women’s ordination among white evangelicals using regression analysis controlling for age and a variety of other demographic controls and found that age was not a significant variable. Other demographic factors we included in our model, such as education, income, and gender were also not significant.

Instead, support for women’s ordination even among the most theologically conservative Americans appears to fit into a broader pattern we have observed in the American public concerning the growing acceptance of women in leadership roles. For example, studies show that virtually all Americans say they would now vote for a qualified woman to be president, compared to roughly half of Americans in the late 1960s. As women have entered the workforce in record numbers and now routinely outnumber men in college and most graduate programs, Americans have grown more comfortable seeing women in charge—even in traditionally male-dominated professions such as religious leadership. The notion of a woman pastor, rabbi, or priest is no longer an alien concept to the vast majority of Americans.

Of course, PRRI’s work shows that vocal minorities of Catholics and white evangelical Protestants alike would still deny women access to the pulpit, citing either tradition or the longstanding patriarchal view that men must retain spiritual headship of congregations and families. This remaining conservative vanguard may continue to shrink over time, however. Scholars who have studied gender relations in the home report that many conservative Protestant families practice a sort of “soft patriarchy,” to use sociologist W. Bradford Wilcox’s term, in which men behave in a less authoritarian manner than their theology might dictate. In practice men and women more often than not share fully in the duties of running the households and rearing the kids—often in response to the economic need for both parents to work outside of the home. Children who grow up in homes where soft patriarchy, or none at all, is the norm might be expected to embody gender equality as adults. It will be the next generation of Catholics and evangelical Protestants who will decide what role women will play in these traditionally hierarchical and conservative religious institutions.