The religiously unaffiliated are a growing political constituency on both sides of the aisle. What do they want from politics?

One of the most dramatic social changes in the United States over the past 30 years has been the growing number of Americans with no religious affiliation, now nearly a quarter of the U.S. population. They are a key part of the Democratic Party’s base, with a slew of books studying them, advocacy groups representing them, and even a new media initiative speaking to them. Understanding this cultural change in the American religious landscape is important for understanding the future of politics amid major demographic shifts.

When we talk about the growth of the unaffiliated, we often tell a story about culture wars and political progressives. Research shows that a major factor driving this growth is the political backlash among liberal and progressive Americans to the organizing efforts of the religious right in the 1980s and 1990s. Because people tend to establish their political views before their religious views solidify later in life, liberal politics tend to lead the choice to select out of religious participation, and so it is easy to assume that this group is just a key part of the Democrats’ political coalition.

Part of that story is absolutely true, but this group is growing and changing quickly, highlighting some big problems with that narrative. Diving into past research and survey data can help to update our story about the unaffiliated with three key facts.

Fact 1: The unaffiliated are a big group, and they aren’t all atheists.

First, the old story mainly focuses on the so-called “activist seculars” among the unaffiliated—atheists, agnostics, and people who are deeply engaged in the work of politics. That profile tends to miss, or even disregard, people who drift away from religion and never return, people who choose other unaffiliated identities, prefer to be spiritual but not religious, or what researchers call “unchurched believers” who change their religious affiliations over time. Once you get to a quarter of the U.S. population, you are dealing with a large group of people who are more centrist—and more politically disengaged—than you might expect.

Fact 2: Religious disaffiliation isn’t just happening on the left.

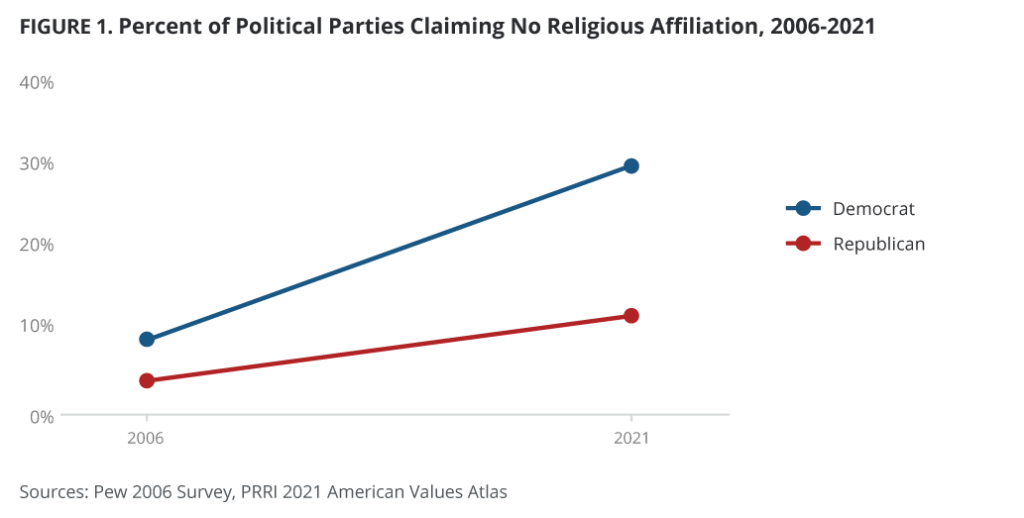

It is more prominent on the left. According to estimates from PRRI, about 30% of self-identified Democrats reported no religious affiliation in 2021. But disaffiliation has been growing among Republicans as well, from about four percent of Republicans in 2006 to 12% of Republicans in 2021.

The implications of this change are not yet clear. It may be that Republican partisans are becoming more untethered from religious institutions, and therefore more likely to invest in other forms of public religion, such as Christian nationalism. Or it may be the case that a new generation of younger Republican partisans will have religion less integrated into their political belief systems than their older counterparts. Either way, researchers and pundits would do well to remember that not all unaffiliated Americans are progressives or center-left Democrats.

The implications of this change are not yet clear. It may be that Republican partisans are becoming more untethered from religious institutions, and therefore more likely to invest in other forms of public religion, such as Christian nationalism. Or it may be the case that a new generation of younger Republican partisans will have religion less integrated into their political belief systems than their older counterparts. Either way, researchers and pundits would do well to remember that not all unaffiliated Americans are progressives or center-left Democrats.

Fact 3: Unaffiliated Americans may not want what politicians think they want.

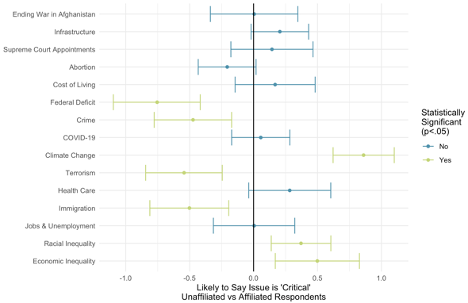

The 2021 PRRI American Values Survey (AVS) included questions about a variety of policy issues, asking respondents whether they thought each was a “critical issue,” “one among many important issues,” or “not that important an issue.” Using this battery, we can focus less on partisanship along a left-right spectrum and more on which issues the unaffiliated prioritize.

Controlling for political partisanship, I looked at the likelihood of unaffiliated respondents saying each issue was “critical” compared to their religiously affiliated counterparts. Unaffiliated respondents in the 2021 AVS were significantly more likely to say that climate change, racial inequality, and economic inequality were “critical” issues than religiously affiliated respondents. They were also marginally more likely to say that health care and infrastructure were also critical issues.

Source: Estimates from logistic regression models for the likelihood of unaffiliated respondents claiming each issue is “critical,” relative to religiously affiliated respondents. Models control for political partisanship. Positive values indicate that unaffiliated respondents are more likely to say an issue is “critical.”

Religiously unaffiliated respondents were also less likely to say that the federal deficit, crime control, terrorism, and immigration were critical issues.

What is most striking about these 2021 issue preferences is the way they do not conform to conventional expectations about this group. We don’t typically think of the unaffiliated as an environmental group, and if one believes in theories about culture wars, we would expect them to be more concerned about the separation of church and state with regard to abortion and appointing Supreme Court justices. In these results, they are no more likely than religiously affiliated respondents to name these as “critical issues.” These results show that other concerns, like environmental protection and infrastructure spending, might be key emerging issues on which leaders can appeal to the unaffiliated as a constituency.

As Democrats continue to try to motivate their base and other political groups try to broaden their constituencies, these results show that we have much more to learn about the broad and diverse section of unaffiliated Americans and voters.

Evan Stewart is a member of the 2021-2022 cohort of PRRI Public Fellows.