Youssef Chouhoud, Ph.D., is an associate professor of political science at Christopher Newport University, and a 2024-2025 PRRI Public Fellow.

Legal battles over same-sex marriage, service refusals, and gender-affirming care frequently position religion and LGBTQ inclusion on opposing sides. That framing has proven politically potent, but it also oversimplifies a more complex and uneven reality. Data from the 2024 PRRI American Values Atlas challenges the assumption that heightened religiosity or religious belief uniformly increases opposition to LGBTQ rights. This Spotlight Analysis examines the extent to which religion influences Americans’ LGBTQ policy preferences, showing that it depends on how religiosity and religious beliefs are measured and which LGBTQ policies are under consideration.

Religion and LGBTQ Inclusion

This analysis focuses on two distinct measures of the role of religion in Americans’ lives. The first is Americans’ religious attendance, a behavioral indicator based on how frequently respondents attend worship services, ranging from “never” to “more than once a week.” For ease of presentation, responses are grouped at the low end (Never/Seldom) and the high end (Weekly or more).

The second measure is support for Christian nationalism, a political-theological worldview that asserts Christianity should play a central role in American public life. PRRI groups Americans into four categories — Christian nationalism Rejecters, Skeptics, Sympathizers, or Adherents — based on their agreement with five statements, including, for example, “The U.S. government should declare America a Christian nation.” More on this measurement can be found here.

Additionally, the 2024 PRRI American Values Atlas includes five specific LGBTQ-related policies:

- Laws that would protect gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people against discrimination in jobs, public accommodations, and housing.

- Allowing a small business owner in your state to refuse to provide products or services to gay or lesbian people if doing so would violate their religious beliefs.”

- “Allowing same-sex couples to marry legally.

- Laws that would prevent parents from allowing their child to receive medical care for a gender transition.

- Laws that require driver’s licenses or government IDs to display a person’s sex at birth rather than their gender identity.

Each question used a four-point scale from “strongly favor” to “strongly oppose.” I recoded these responses and collapsed them into Favor/Strongly Favor LGBTQ rights and Oppose/Strongly Oppose LGBTQ rights.[1]

To isolate the influence of religious attendance and support for Christian nationalism from other variables, my analysis estimates predicted probabilities, which allows for comparisons across these measures while holding other factors, such as age, education, gender, and race, constant. For example, frequent church attenders tend to be older, and older Americans are generally less supportive of transgender rights, so predicted probabilities help clarify the independent role religious attendance plays. Additionally, my analysis is limited to self-identified Christians in order to examine variation within the country’s largest religious tradition.

Key Patterns in the Data

The results of this analysis point to two main takeaways that underscore the need for nuance when discussing the association between religion and LGBTQ rights.

First, the effect of the role of religion depends on how it is understood. Support for Christian nationalism is a much stronger predictor of opposition to LGBTQ inclusion than religious attendance. Christian nationalism not only predicts lower support overall, it also appears to amplify resistance to policies viewed as representing broader cultural change. Second, LGBTQ-related policies are not viewed uniformly.

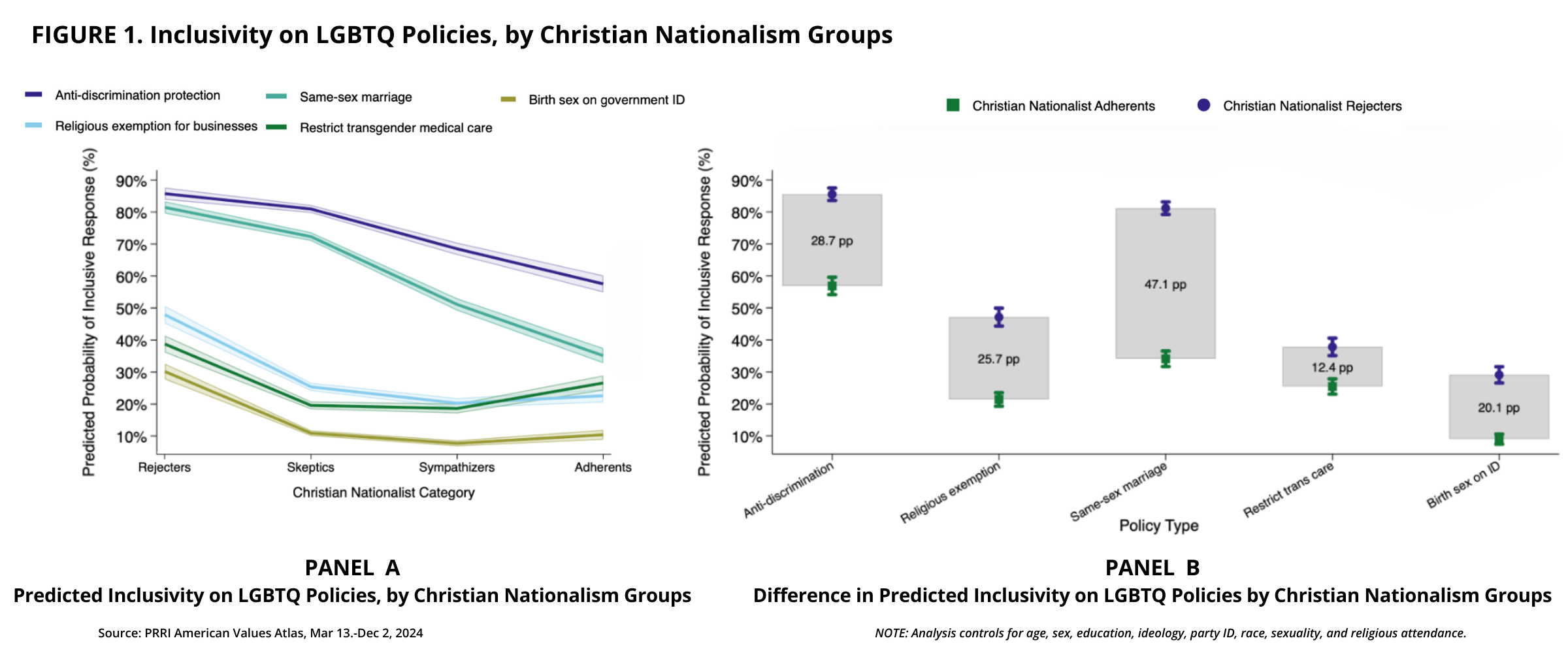

Across all five issues, Christian nationalism Adherents are consistently and significantly less likely to express inclusive views than Rejecters (Panel A in Figure 1), with gaps ranging from 12 to 47 percentage points depending on the policy (Panel B in Figure 1). These divides are particularly stark on issues that are symbolically charged, such as same-sex marriage and transgender rights, where the ideological stakes are perceived to challenge traditional or conservative Christian norms around identity and morality.

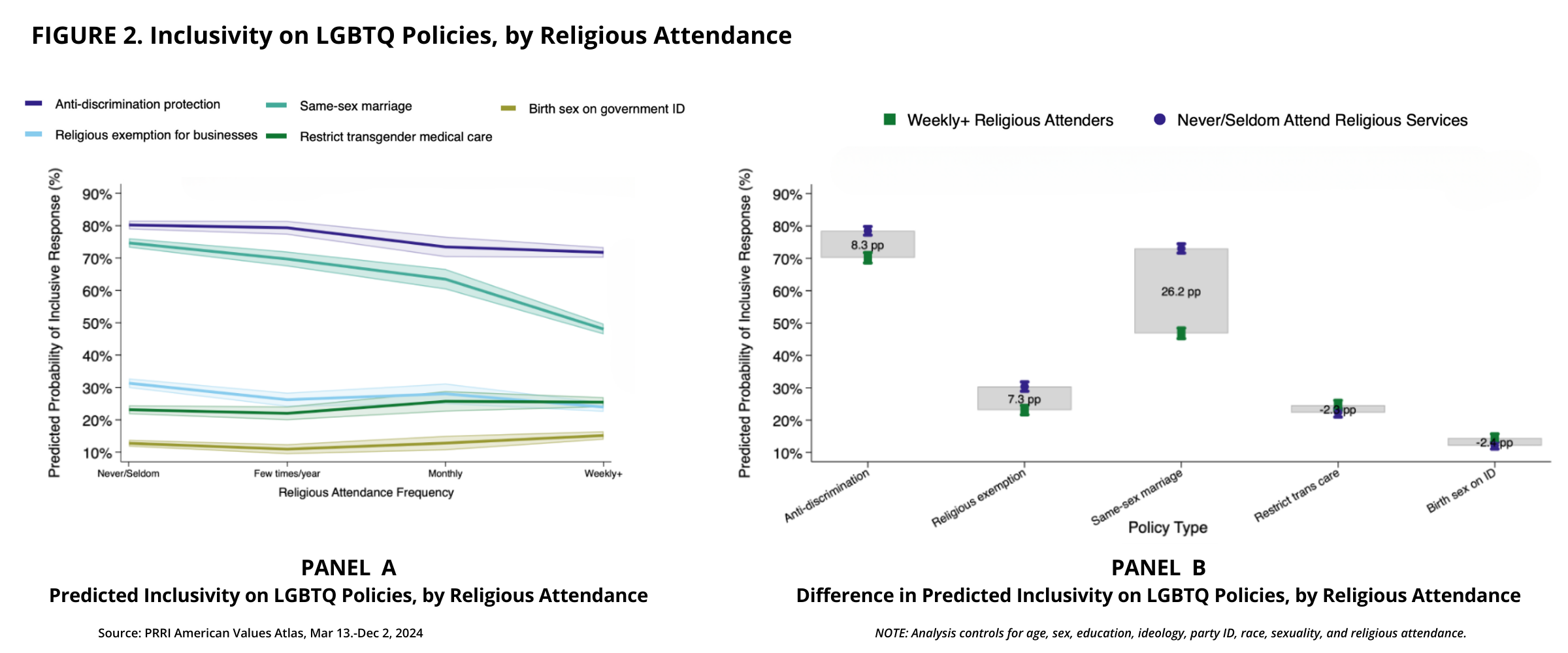

Religious attendance, by contrast, shows a weaker and more inconsistent relationship. On some issues, including nondiscrimination protections and ID policies, weekly attenders and infrequent attenders are statistically indistinguishable (Panel A in Figure 2). Where gaps do emerge, they are narrower, typically between 7 and 27 percentage points (Panel B in Figure 2).

To sum up, support for same-sex marriage generates the widest divides across both measures of religiosity, reinforcing its symbolic weight in cultural discourse. By contrast, nondiscrimination laws enjoy high levels of support across most religious categories, suggesting a baseline consensus around fairness in public life. Policies related to transgender rights, particularly medical care for minors and ID laws, receive the least support overall, even among those otherwise inclined toward inclusion. This suggests that relative unfamiliarity or discomfort with transgender issues may be dampening support, regardless of religious practice or beliefs.

Why These Results Matter

These findings complicate common narratives that treat religion as a singular, coherent force in American public life and challenge assumptions that equate personal religiosity with blanket opposition to LGBTQ rights. Many American Christians who regularly attend church support inclusive policies. On the other hand, Christians who support Christian nationalist ideals express much greater resistance.

Understanding this distinction is crucial. It highlights the need to disentangle religious practice from political beliefs, such as Christian nationalism, and opens space for coalition-building among religious Americans who do not see their faith as incompatible with inclusion.

At the same time, the limited support for transgender rights across the board suggests that opposition to these policies cannot be attributed solely to religious belief or practice. Even among more presumably supportive groups, these issues lag behind others in public acceptance. Religion, then, is just one of several factors that activists, educators, and policymakers must consider as they seek to explain and potentially shift opinion in this space.

A More Nuanced Conversation

Framing the LGBTQ rights debate as one that pits “religion” against “inclusion” obscures meaningful variation within religious communities themselves, especially American Christians. This analysis underscores the importance of being specific in how religiosity and religious beliefs are defined and measured. It also reinforces the need to understand how particular issues, such as transgender rights, may activate different forms of resistance, only some of which are rooted in religion.

By refining how we talk about religion’s role in shaping public opinion, we can better identify both sources of opposition and opportunities for engagement. Moving beyond reductive binaries allows for a more accurate — and more productive — conversation about faith, identity, and inclusion in American life.

[1] Higher values consistently reflect more inclusive stances, such as favoring protections or marriage equality, or opposing bans and restrictions.