Drs. Danielle Boaz, Michael R. Fisher Jr., Allyson Shortle, and Dheepa Sundaram are 2023-2024 PRRI Public Fellows studying the intersection of politics, religion, and racial justice. This Spotlight Analysis details the findings of their original, collaborative research conducted with support from PRRI.

It’s been nearly 30 years since the passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act of 1996 that was viewed as “the end of welfare as we know it.” In his landmark study on welfare, Martin Gilens (1999) argues that opposition to government assistance programs for the poor is largely driven by racial stereotypes, specifically by the perception that most people on them are Black and that they are less committed to a hard work ethic than other Americans. In this Spotlight, we extend this line of inquiry by examining attitudes toward government assistance for the poor at the nexus of race and religion, nearly 30 years after the institution of welfare reform. We also explore an under-examined facet of attitudes toward government assistance—perceptions about the role of civil society and religious communities (e.g., religious nonprofits) in supporting people in need.

In April of 2024, with support from Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI), we conducted an original national nonprobability survey of 1280 Americans using the YouGov survey platform which matched and weighted our sample to make it representative of the U.S. population. The survey’s results corroborate findings from Gilens’s foundational work, while revealing a more nuanced picture of Americans’ attitudes toward providing government assistance—once religious and racial factors and the type of sector delivering services are considered together.

Disparities in Support for Government-funded Assistance Programs

Perceptions of Recipients

We first examined respondents’ perceptions of government assistance program recipients. We asked whether respondents perceived recipients to be actively looking for employment or not. Across racial groups, two-thirds of all respondents believe people receiving government assistance actively seek employment. However, white evangelicals (54%) are far less likely than evangelicals of color (78%) to believe that government assistance recipients are looking for work. This finding reveals that whereas evangelical identification is associated with increased pessimism for white evangelicals, it is associated with increased optimistic views of social welfare recipients for evangelicals of color.

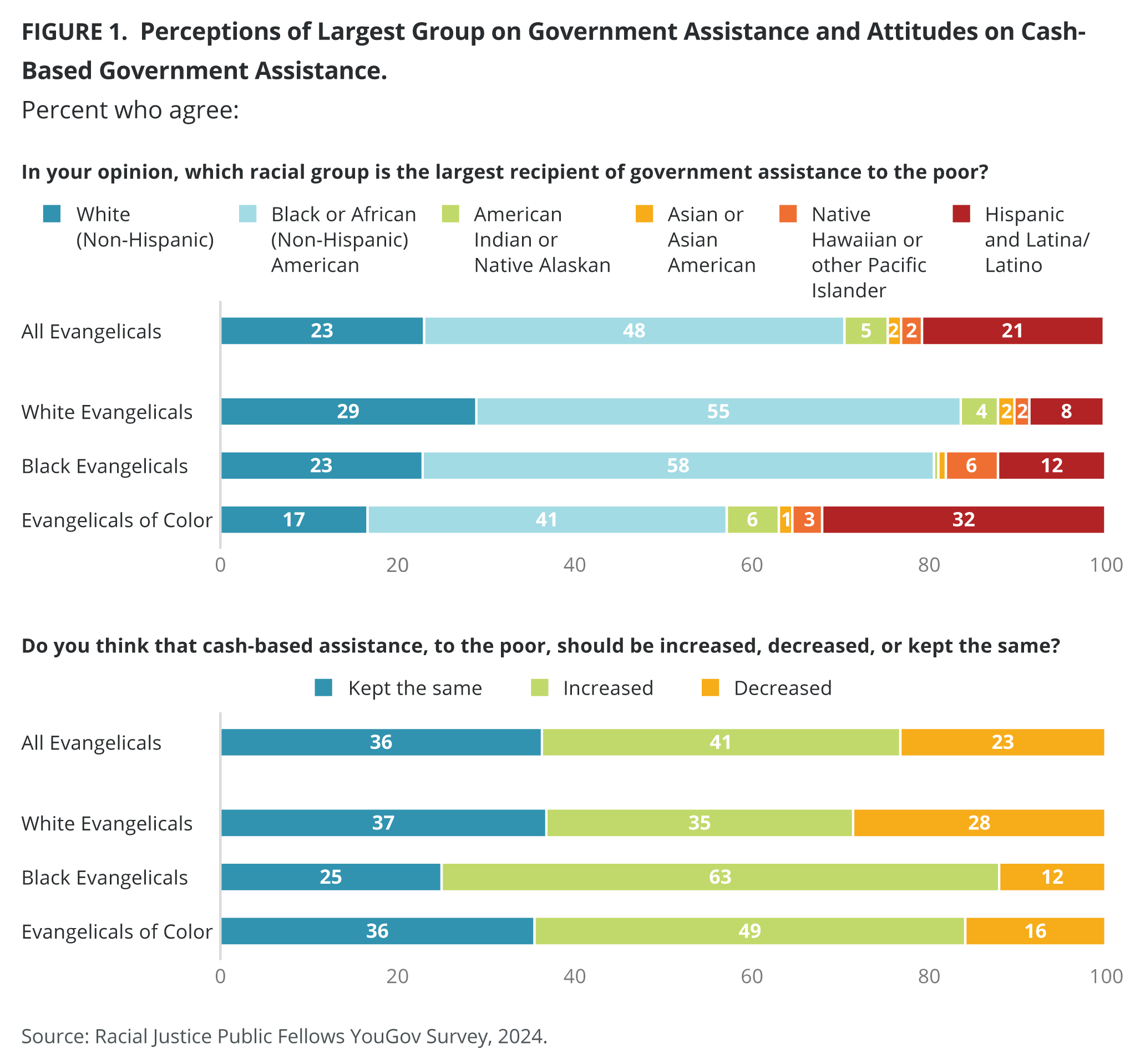

Our survey then asked respondents which racial group they view as the top recipients of government assistance. Respondents did not reach a consensus on which racial group was the main beneficiary of social welfare assistance, revealing a pluralism of stereotypes. However, some interesting associations appear once we isolate evangelicals’ attitudes. White evangelicals and evangelicals of color believe that Black people are the majority receiving government assistance at higher rates than the broader population of their demographic group, 55% and 48% respectively. This is a longstanding, albeit false, perception of the primary beneficiaries of government assistance to the poor.

Policy Attitudes of Evangelicals and Christian Nationalism Supporters

Our survey also examined policy attitudes finding that white evangelicals (35%) are significantly less supportive than Black evangelical respondents (63%) and the general public (46%) of increasing cash-based government assistance to the poor. These percentages reveal large racial and religious divides on cash-based assistance.

Our survey also compared how these policy attitudes compare across race and support for Christian nationalism, an exclusionary ethnocultural ideology associated with white supremacy and Christian domination. We use PRRI’s standard metric of Christian nationalism to compare the sample’s white versus Black Christian nationalists, who we define as respondents scoring above average on the Christian nationalism scale. Unsurprisingly, white Christian nationalists were significantly less likely to prefer increasing cash-based assistance to the poor at 27%, compared with 46% of the general public. However, Black Christian nationalist respondents were the survey’s biggest proponents of cash-based assistance, with a large 63% favoring increasing such forms of assistance. Only 9% of Black Christian nationalist respondents supported decreasing such programs, compared with 35% of white Christian nationalists. We interpret these findings as evidence that Christian nationalism operates differently for white and Black populations.

There was one issue — work requirements — on which religious respondents and religious respondents of color largely agree. We find that evangelical respondents are overwhelmingly supportive of work requirements for the poor to receive government assistance: 86% of white evangelicals and 87% of evangelical respondents of color. Similar trends are observable for Black and Hispanic evangelical respondents. Most white Christian nationalists (89%) and Christian nationalists of color (87%) favor work requirements. This finding reveals the evolution of the social welfare debate, as one of the most contentious elements of the 1990s welfare reform appears to have become widely accepted three decades later.

Disparities in Support for Religious Nonprofit Assistance

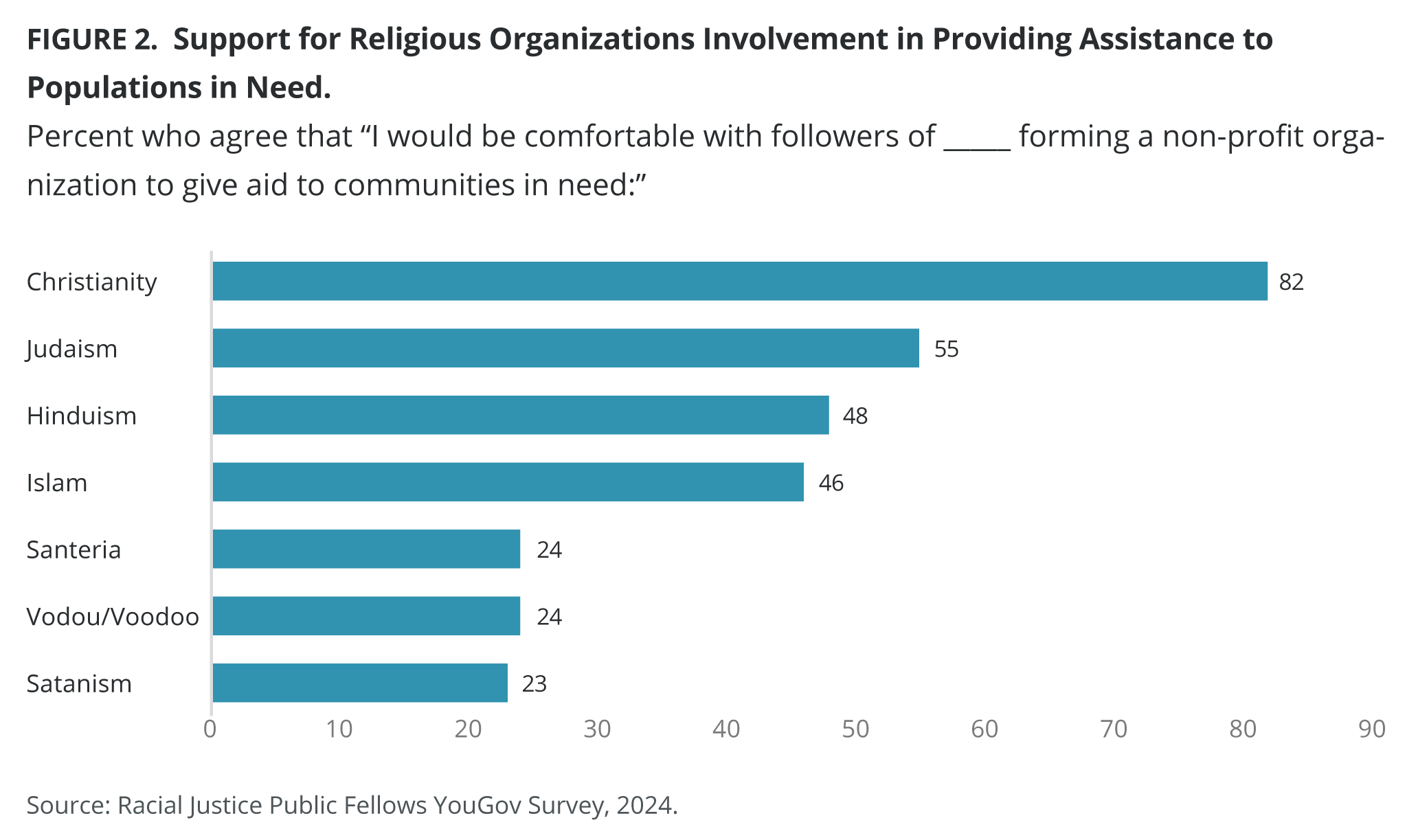

Religious nonprofit organizations represent major service delivery actors both nationally and globally, but they are an under-examined agent of social welfare assistance. We therefore asked several questions in our survey about religious nonprofits to reflect the way that many people receive assistance. Our survey revealed disparities regarding the respondents’ support of religious organizations being involved in aiding vulnerable populations. For example, one of our survey questions asked respondents the following: “I would be comfortable with followers of _____ forming a non-profit organization to give aid (i.e., food, water, medical supplies) to communities in need.” Respondents were provided with a list of seven religions, of which they were asked to “select all that apply.” They also had the option of indicating “none of the above.”

Most respondents (82%) were comfortable with Christians forming a nonprofit organization to give aid to communities in need. Around half of respondents were comfortable with followers of Judaism (55%), Hinduism (48%) and Islam (46%) organizing to provide such services. However, less than one-quarter of respondents approved of followers of Santeria (24%), Vodou/Voodoo (24%), or Satanism (23%) creating a non-profit to support communities in need.

Respondents were also asked, “Following an emergency or disaster, a non-profit organization associated with ______ should be able to distribute aid to members of their own religion before followers of other religions.” They were given the same instructions and list of religions as the previous question. Nearly half of the respondents (48%) were comfortable with Christians prioritizing other Christians over adherents of different faiths. Around one-fourth believed that Jews (28%), Muslims (27%), and Hindus (25%) should be able to provide aid to members of their own religion before devotees of other religions. Very few respondents believed that followers of Santeria (14%), Satanism (13%), or Vodou/Voodoo (12%) should be able to prioritize members of their faith.

Democracy and Religion’s Complicated Relationship Remains – with Clear Racial Implications

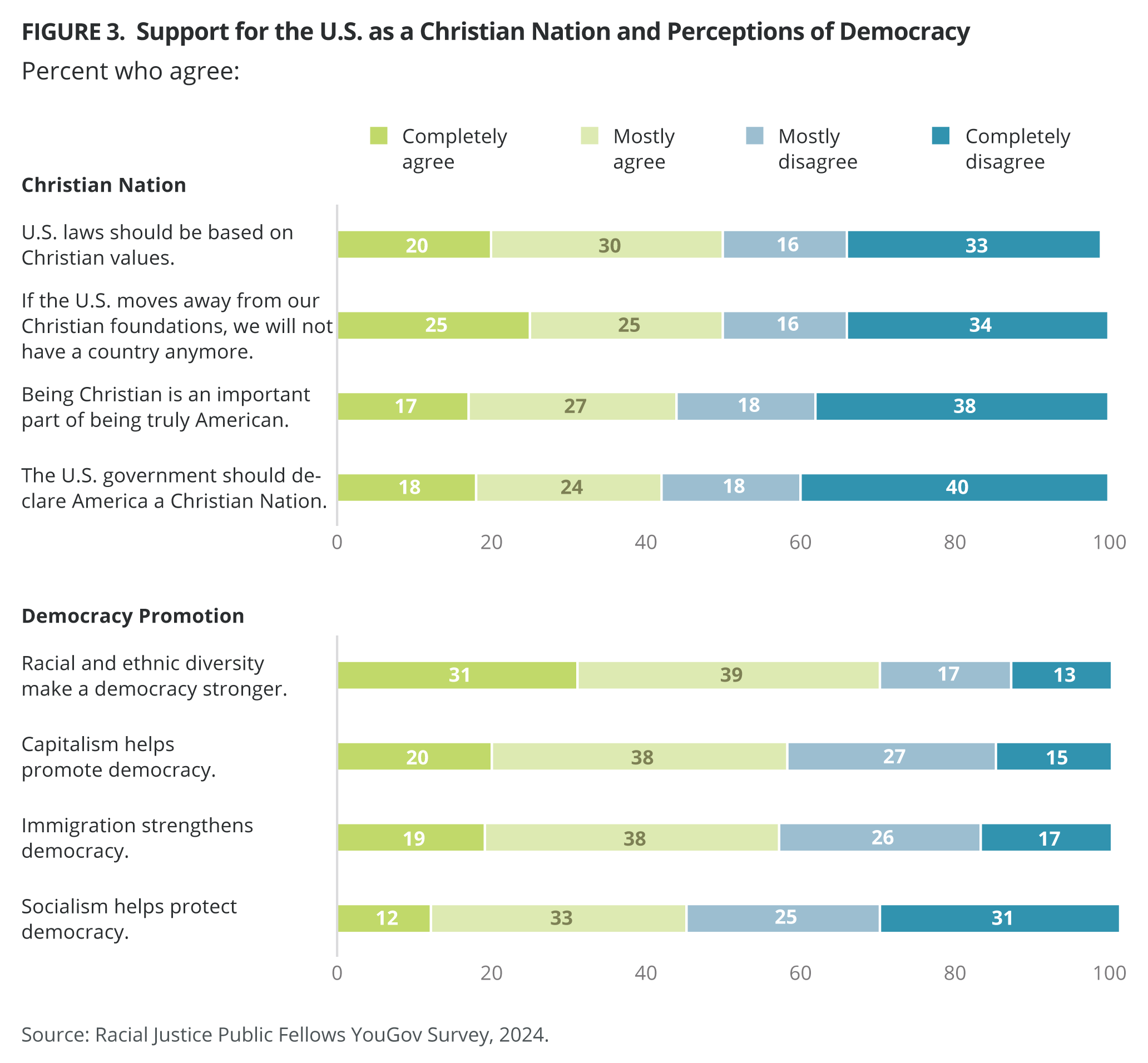

We also asked about how religion aligned with democracy, capitalism, and socialism. Nearly two-thirds of respondents (64%) believe that religion helps promote democracy and 70% view racial diversity as an important feature of democracy. When comparing with questions on social welfare, we find that 38% of people who view religion as having a role in social welfare view government assistance as a way to help folks escape poverty, an 8-point jump over the survey respondents overall (30%).

Filtering our results to white respondents who identified as Christian (Protestant denominations or Catholic) and very conservative or mostly conservative (referred to as “white Christian conservatives” going forward), our survey results show that this group of respondents believe that their religion promotes democracy (78%) and teaches that racial discrimination is wrong (97% compared with 86% of all respondents). White Christian conservative respondents’ views on democracy show a 14-point jump when compared with respondents overall (64%) and an 11-point advantage over the general respondent pool. However, only 55% of white Christian conservatives compared with 70% of the general respondent pool believe that racial and ethnic diversity strengthens a democracy. In line with this finding, a high percentage of white Christian conservatives (92%) hold the view that Black folks should work their way up like other immigrant/racial groups to be as successful as white people, compared with 63% of respondents overall, while 78% believe Blacks folks should try harder, a view held by only 40% of the respondent pool overall. Further, 43% of white Christian conservatives think Christians should have dominion over U.S. laws compared with 35% of respondents overall, while 69% think the U.S. is a Christian nation and 85% think the U.S. should be based on Christian values, a position held by 50% of the general public.

How Democracy and Racial Diversity Become Christian Nationalist Values

Our findings show that most people view social assistance through a racialized lens in which Black people are cast as the primary recipients of government assistance for the poor, a belief that is nearly universally shared among white Christian conservatives. This aligns with our finding that most people saw religious organizations that distribute disaster aid as within their rights to discriminate based on religion. Interestingly, this was not only true for Christian-identifying respondents but also for most of those identifying with other traditions as well. A significant plurality of respondents views the U.S. as a Christian nation based on Christian values, a finding that becomes more pronounced when examining white Christian conservatives.

Overall, our survey finds that respondents have internalized white Christian nationalist views as commensurate with the U.S. democratic government and capitalist economic systems. When considering attitudes toward government assistance for the poor and disaster aid and comparing our findings with perceptions of Black people’s work ethic 30 years ago, we see racial stereotypes have not only persisted but now seem to explain attitudes regarding social assistance that are at odds with religious values regarding racial discrimination and to a lesser degree gender discrimination.

Our findings point to the influence of Christian nationalist views which both valorize racial diversity while maintaining racist views of work and social assistance. In this sense, this study suggests that racial stereotypes and resentments continue to shape views of government assistance for the poor and reflect how Christian nationalist proponents have been successful in convincing a majority of the U.S. to disregard systemic racial discrimination as a factor in poverty rates. Instead, fabricated racial disparities in need-based assistance are painted as the fault of the recipients. The survey results also point to the need for additional research on the growing impact of Christian nationalist views on non-white and non-Christian communities in the U.S.

Our findings point to the influence of Christian nationalist views which both valorize racial diversity while maintaining racist views of work and social assistance. In this sense, this study suggests that racial stereotypes and resentments continue to shape views of government assistance for the poor and reflect how Christian nationalist proponents have been successful in convincing a majority of the U.S. to disregard systemic racial discrimination as a factor in poverty rates. Instead, fabricated racial disparities in need-based assistance are painted as the fault of the recipients. The survey results also point to the need for additional research on the growing impact of Christian nationalist views on non-white and non-Christian communities in the U.S.