Race and the Criminal Justice System

A slim majority (51 percent) of Americans do not believe that blacks and other minorities receive treatment equal to whites in the criminal justice system, while 46 percent believe that they do.

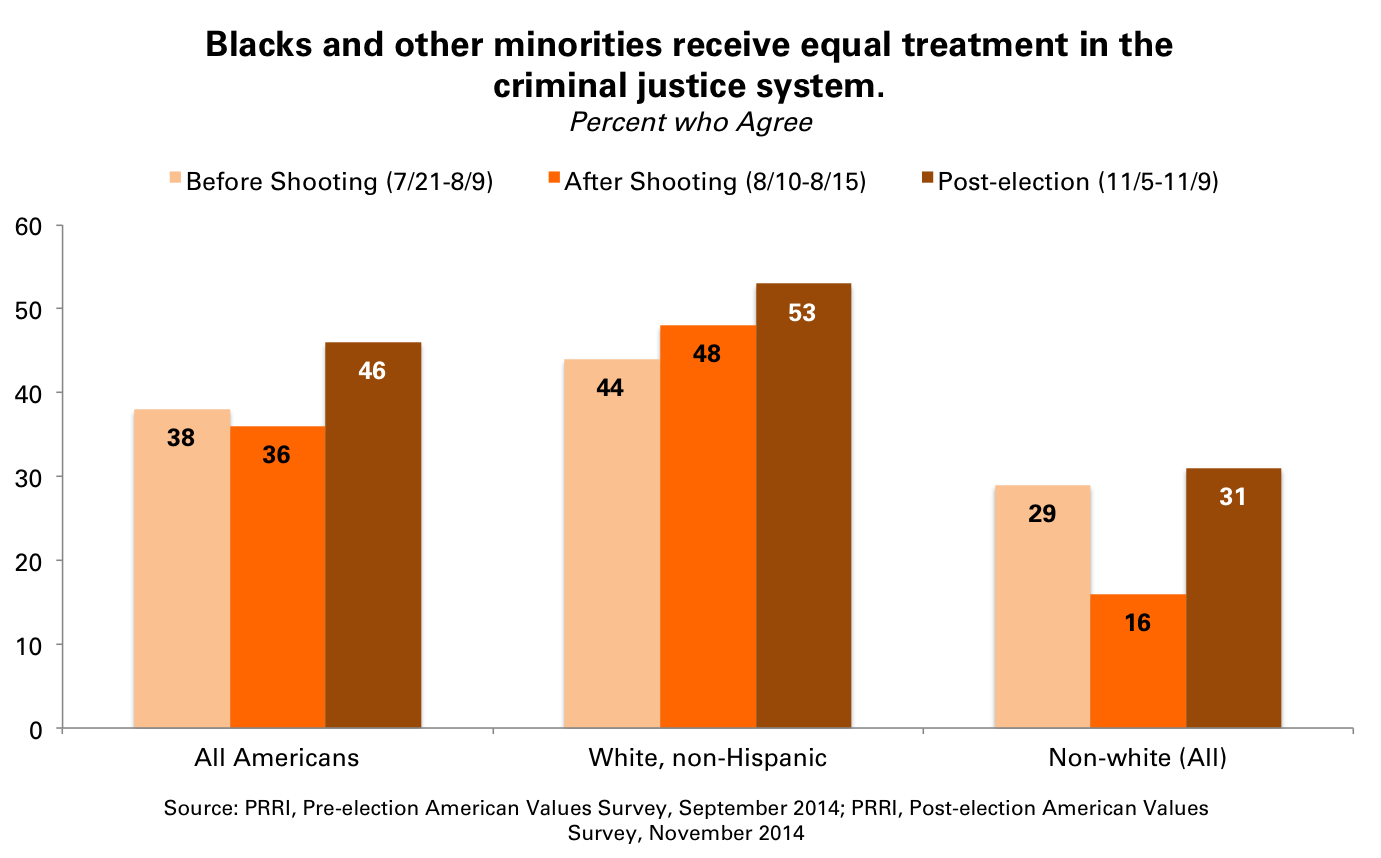

Current opinions about race in the criminal justice system represent a modest downward shift from August 2014, when, in the 2014 Pre-election American Values Survey, a majority (56 percent) of Americans said that blacks and other minorities did not receive the same treatment as whites in the criminal justice system. The field period for that earlier survey was from July 21 to August 15—before, during, and after the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo.

In the weeks preceding the shooting, fewer than 3-in-10 (29 percent) non-white Americans agreed that blacks and other minorities receive equal treatment in the criminal justice system. That number plummeted 13 percentage points—to 16 percent—immediately afterward.

The 2014 Post-election American Values Survey, which was in the field from November 5 to November 9, 2014, finds that the percentage of white, non-Hispanic Americans who believe blacks and other minorities receive equal treatment in the criminal justice system jumped from 44 percent before the shooting to 53 percent months after the shooting.

Overall, views about the fairness of the criminal justice system are highly stratified by race. A majority (53 percent) of white Americans believe that black and other minorities receive equal treatment in the criminal justice system compared to 42 percent who disagree. Black Americans are half as likely (24 percent) to affirm this statement, and 73 percent disagree.

Treatment of Minorities by Police

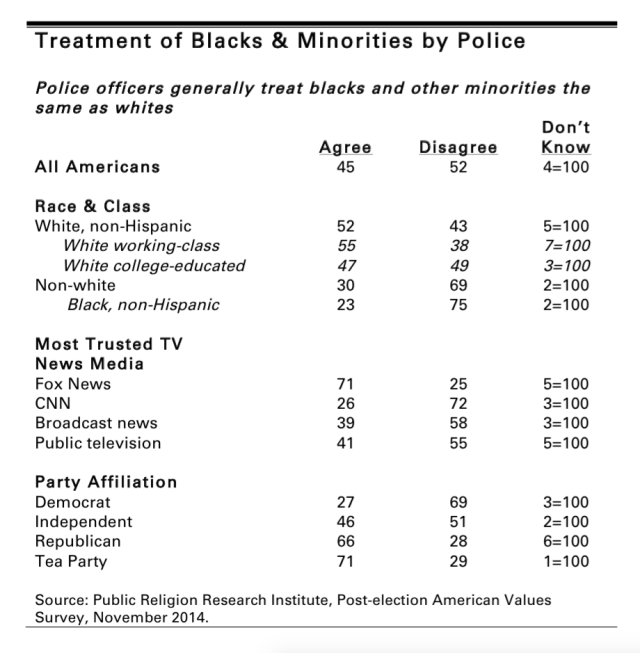

Americans’ views about the fairness of law enforcement officers largely mirror views about equity in the criminal justice system. A slim majority (52 percent) of Americans do not believe that police officers treat blacks and other minorities the same as whites, while close to half (45 percent) disagree. There are notable divisions on this question by race, political affiliation, and most-trusted media source.

Nearly two-thirds (66 percent) of Republicans and more than 7-in-10 (71 percent) Tea Party members agree that police officers generally treat blacks and other minorities the same as whites. Roughly as many Democrats (69 percent) disagree, while independents closely resemble the general public. A majority (52 percent) of white Americans also believe that police officers generally treat all people the same regardless of race, while more than 4-in-10 (43 percent) disagree. Three-quarters (75 percent) of black Americans reject this statement. More than 7-in-10 (71 percent) Americans who most trust Fox News agree that police generally treat people the same regardless of race. Less than half of Americans who most trust any other media source agree.

Mandatory Minimum Sentences for Nonviolent Offenders

Americans generally agree that mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent offenders should be eliminated. More than three-quarters (77 percent) of Americans say that mandatory minimum prison sentences for nonviolent offenders should be eliminated so that judges can make sentencing decisions on a case-by-case basis. One-in-five (20 percent) Americans oppose this policy change. There is bipartisan and cross-religious support for changing mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent offenders. Approximately 8-in-10 Democrats (83 percent) and independents (80 percent) and two-thirds (66 percent) of Republicans support this policy. Similarly, majorities of all major religious groups—including 90 percent of religiously unaffiliated Americans, 76 percent of Catholics, 76 percent of minority Protestants, 76 percent of white mainline Protestants, and 65 percent of white evangelical Protestants—support eliminating mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent offenders.

Public Religion Research Institute is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan organization specializing in research at the intersection of religion, values, and public life. For more information, visit: publicreligion.org.