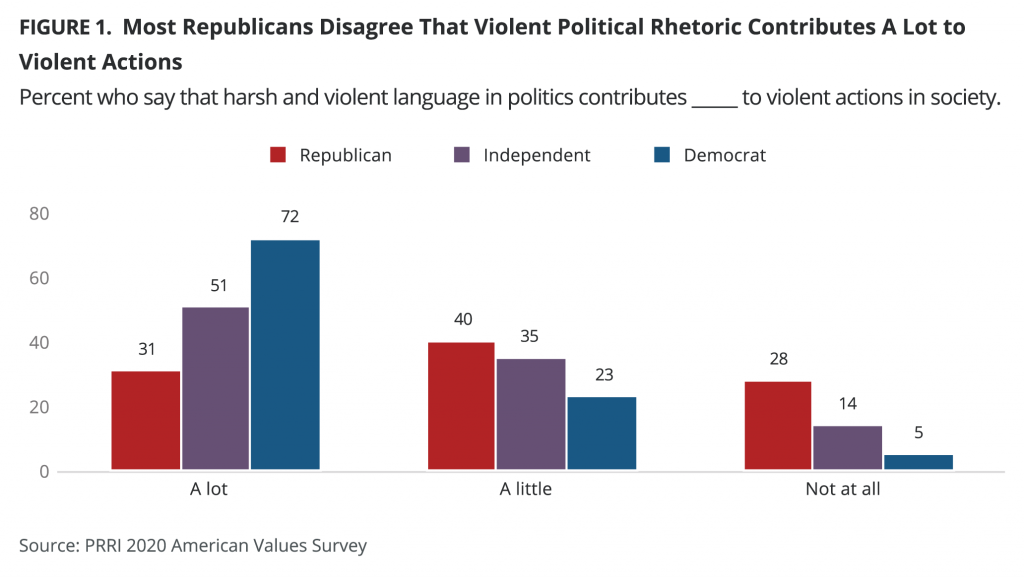

According to data collected just prior to the 2020 election, a slim majority of Americans (51%) are concerned that harsh and violent language in politics contributes “a lot” to violent actions in society. An additional 32% say violent rhetoric contributes “a little” to violent actions, and just 16% say it does not contribute at all.

During President Trump’s January 6 rally to protest his electoral loss, the president and his Republican allies encouraged Trump supporters to “fight much harder” against “bad people” and to march on the U.S. Capitol building, where Congress was in session to certify the Electoral College votes from the election. This led to a violent mob storming the Capitol, breaking through police barricades, and causing several deaths and injuries.

In the aftermath of the riot, Trump was banned from several social media platforms, including Twitter and Facebook, for encouraging or inciting violence. Additionally, the social media platform Parler faced scrutiny for enabling right-wing extremists to organize violence targeted against Democratic officials. Parler was dropped from the Apple App Store and the Google Play Store, as well as the Amazon Web Services hosting platform, effectively ending the service unless it can find another host.

Unsurprisingly, there are deep partisan divides in linking violent rhetoric to violent actions. Democrats (72%) are more than twice as likely as Republicans (31%) to say that violent rhetoric contributes a lot to violent actions. Four in ten Republicans (40%) say violent rhetoric contributes a little to violent actions, and 28% say it does not contribute at all. Less than one in four Democrats (23%) say it contributes a little, and just five percent say it does not contribute at all. Independents generally resemble the country as a whole, with 51% saying violent rhetoric contributes a lot to violent actions, 35% saying it contributes a little, and 14% saying it does not contribute at all.

As previous PRRI research has indicated, the 40% of Republicans who most trust Fox News are generally more extreme in their views than Republicans who trust other news sources. However, attitudes toward violent rhetoric are not just limited to Fox News Republicans. Fox News Republicans (30%) are just as likely as Republicans who get their news from other sources (31%) to say that violent rhetoric contributes a lot to violent language.

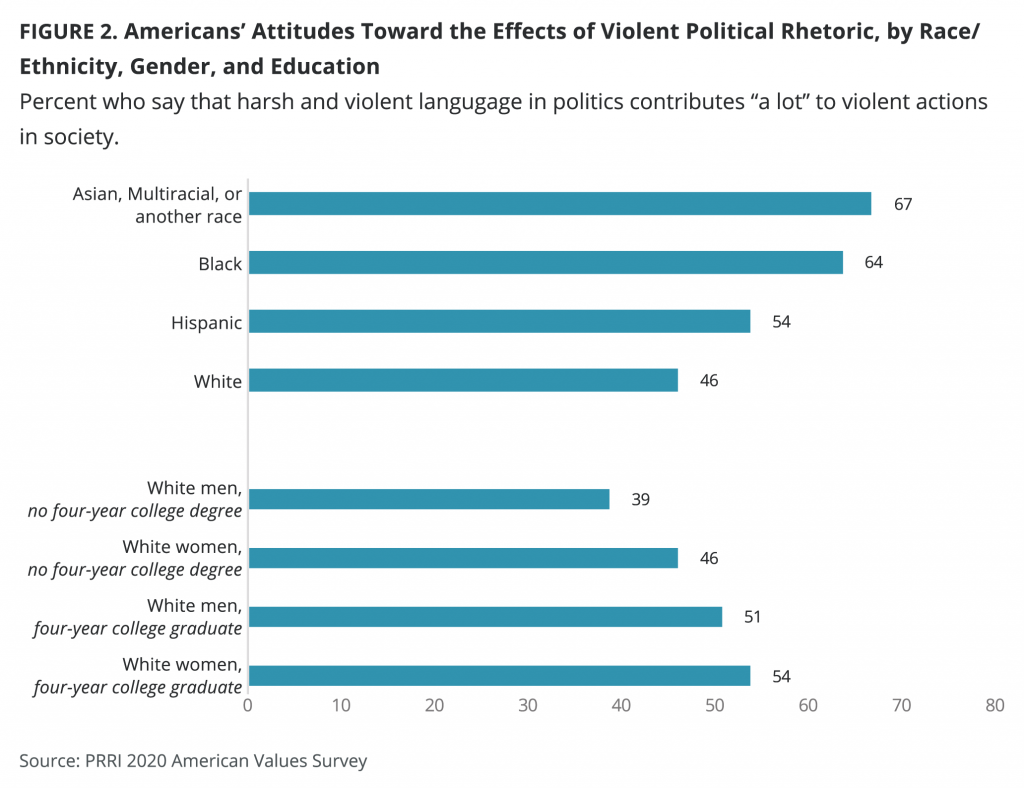

Americans who are Asian, multiracial, or another race (67%), Black Americans (64%), and Hispanic Americans (54%) are most likely to say that violent political rhetoric contributes a lot to violent actions, while around one in four members of these groups say it contributes a little (27%, 24%, and 25%, respectively). Around one in five Hispanic Americans (20%) say that violent rhetoric has no effect on violent action, slightly more than among Black Americans (12%) or Americans who are Asian, multiracial, or another race (6%).

White Americans are more divided on the issue than Americans of other races. Just under half of white Americans (46%) say that violent political rhetoric contributes a lot to violent actions, while around one-third (36%) say it contributes a little and 17% say it does not contribute at all.

However, white Americans see some divides along gender and education lines. Similar shares of white men and white women with at least a four-year college degree say that violent actions contribute a lot (51% and 54%, respectively), while around one-third say it contributes a little (38% and 32%, respectively), and just over one in ten say it does not contribute at all (11% and 14%, respectively).

There is a deeper divide between white men and women who do not hold four-year college degrees. Fewer white men without a college degree (39%) than white women without a college degree (46%) say that violent political rhetoric contributes a lot to violent actions, while similar shares of these groups say it contributes a little (38% and 34%, respectively) or not at all (23% and 18%, respectively).

The belief that violent political rhetoric contributes to violent actions correlates closely with age. Americans over age 65 are most likely to say violent rhetoric contributes a lot to violent actions (61%), which is significantly more likely than Americans ages 50 to 64 (55%), ages 30 to 49 (48%), and ages 18 to 30 (43%). Americans ages 18 to 29 (22%) and ages 30 to 49 (20%) are both more likely than Americans ages 50 to 64 (12%) and over age 65 (11%) to say that violent rhetoric does not contribute at all to violent actions.

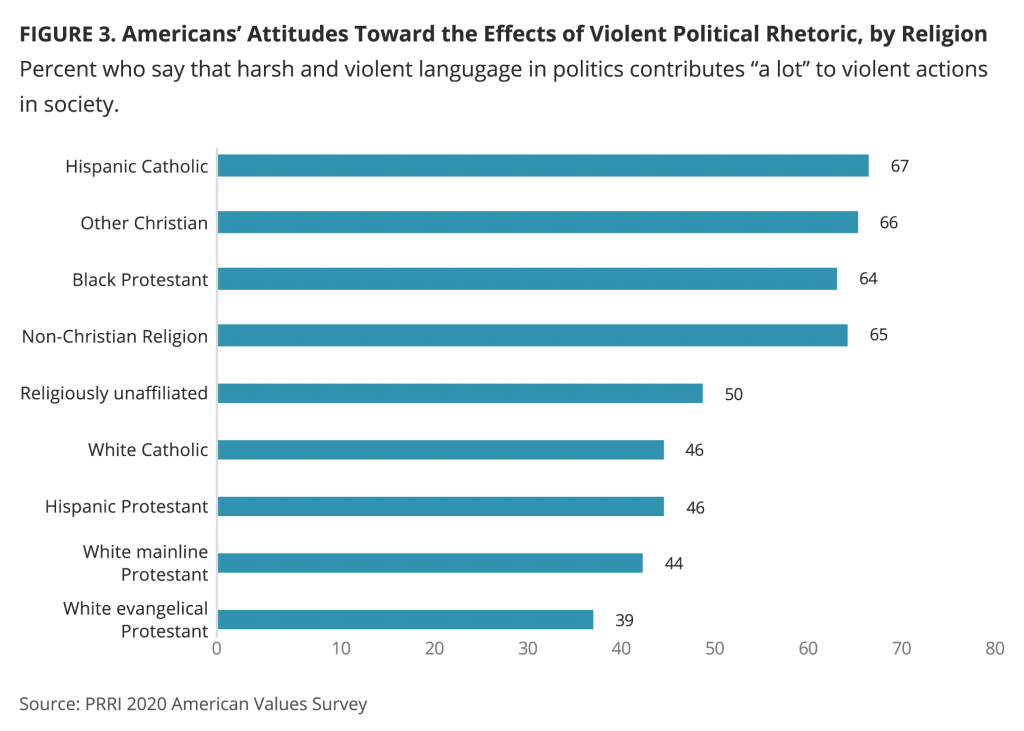

Religious Americans generally divide into two groups over the issue of violent rhetoric. In the first group, less than half of white Christians and Hispanic Protestants believe that violent language contributes a lot to violent actions in society, including 39% of white evangelical Protestants, 44% of white mainline Protestants, 46% of white Catholics, and 46% of white Protestants. In the second group, around two-thirds of non-white Christians and non-Christians say violent rhetoric contributes a lot to violent actions. This includes 64% of Black Protestants, 65% of non-Christian religious Americans, 66% of other Christians, and 67% of Hispanic Catholics. Religiously unaffiliated Americans fall in between the two groups, with half (50%) saying that violent rhetoric contributes a lot to violent actions.