Ever since the 2012 election, when the religiously unaffiliated served as a cornerstone of the coalition that propelled Barack Obama to a second presidential term, this increasingly influential group has received substantially more airtime. These media portrayals – most recently, a series for NPR’s Morning Edition – are helping to illuminate the depth and complexity of the unaffiliated, although the story is somewhat more complicated than some initial analysis suggests. Most importantly, the classification of the unaffiliated as “nones,” as well as perspectives on why more and more Americans are choosing not to affiliate, deserve a second look.

In the piece, NPR relies primary on data from last fall’s Pew report on the unaffiliated. In the title of the report, Pew refers to the religiously unaffiliated as “nones,” although this title does not do justice to this group’s diversity. PRRI’s 2012 Pre-Election American Values Survey noted that religiously unaffiliated Americans are comprised of three discrete subgroups, which have distinct religious and demographic profiles. Notably, about one-in-four unaffiliated Americans describe themselves as religious, despite their lack of denominational identity:

- “Unattached believers” (23%): describe themselves as religious despite having no formal religious identity, and are more likely than the general population to be black or Hispanic and to have lower levels of educational attainment;

- “Seculars” (39%): describe themselves as secular or not religious, and roughly mirror the general population in terms of racial composition and levels of educational attainment;

- “Atheists and agnostics” (36%): identify as atheist or agnostic, and are more likely than the general population to be non-Hispanic white and to have significantly higher levels of educational attainment.

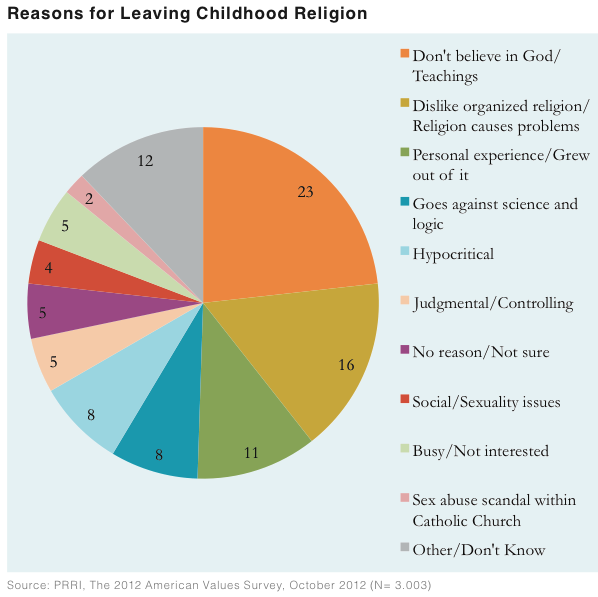

NPR also quotes Harvard scholar Robert Putnam, who ascribes most of the growth of the religiously unaffiliated to the rise of the culture wars and politicized Christianity, when “religion publicly became associated with a particular brand of politics.” However, when religiously unaffiliated Americans who were raised with a religious identity are asked why they left the religion of their childhood, politicized religion seems to barely register. Nearly one-quarter (23%) say they ceased to believe in the teachings of their childhood faith or in God, while 16% articulate antipathy toward organized religion. Around 1-in-10 (11%) point to negative personal experiences with religion or life experiences in general, while a similar number cite their perception that religion is at odds with scientific principles and logic (8%) or that religion or religious people are hypocritical (8%).

NPR also quotes Harvard scholar Robert Putnam, who ascribes most of the growth of the religiously unaffiliated to the rise of the culture wars and politicized Christianity, when “religion publicly became associated with a particular brand of politics.” However, when religiously unaffiliated Americans who were raised with a religious identity are asked why they left the religion of their childhood, politicized religion seems to barely register. Nearly one-quarter (23%) say they ceased to believe in the teachings of their childhood faith or in God, while 16% articulate antipathy toward organized religion. Around 1-in-10 (11%) point to negative personal experiences with religion or life experiences in general, while a similar number cite their perception that religion is at odds with scientific principles and logic (8%) or that religion or religious people are hypocritical (8%).

As Putnam notes, America remains an extraordinarily religious country – but that includes a significant number of those who choose not to affiliate with a particular religious tradition. After all, nearly two-thirds of religiously unaffiliated Americans say that God is a person (31%) or an impersonal force (34%), while three-in-ten (30%) say they do not believe in God. This underscores the need for a more nuanced view of the growing numbers of Americans who are “losing their religion.”