Drs. Michal Raucher and Anne Whitesell were 2024-2025 PRRI Public Fellows studying the intersection of politics, religion, and reproductive rights. This Spotlight Analysis details the findings of their original, collaborative research conducted with support from PRRI.

Since the 2022 Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization U.S. Supreme Court decision, states have created their own distinct laws and regulations regarding abortion access. This patchwork of laws has confused pregnant people and their doctors about how these regulations would be implemented. Even worse, women have died because they and their medical providers thought that the emergency medical care they sought was illegal. Medical providers have left states where the standard of care for a miscarriage was legally considered an abortion, which meant they could not perform that care. This Spotlight Analysis examines Americans’ views on abortion laws and highlights the widespread confusion over the terms “abortion” and “miscarriage,” showing that abortion restrictions drive public misunderstanding with serious consequences.

Measuring Americans’ Confusion About Abortion and Miscarriage

Research conducted before the Dobbs decision reveals that definitions of abortion and miscarriage are socially constructed. Furthermore, the relationship between religious identity and views on abortion may shape how people understand a given reproductive scenario. In May 2025, with support from PRRI, we worked with Ipsos to survey a representative, random sample of 1,000 Americans about their understanding of miscarriage and abortion. Each participant read five vignettes and indicated whether they thought the described scenario was an abortion or a miscarriage.

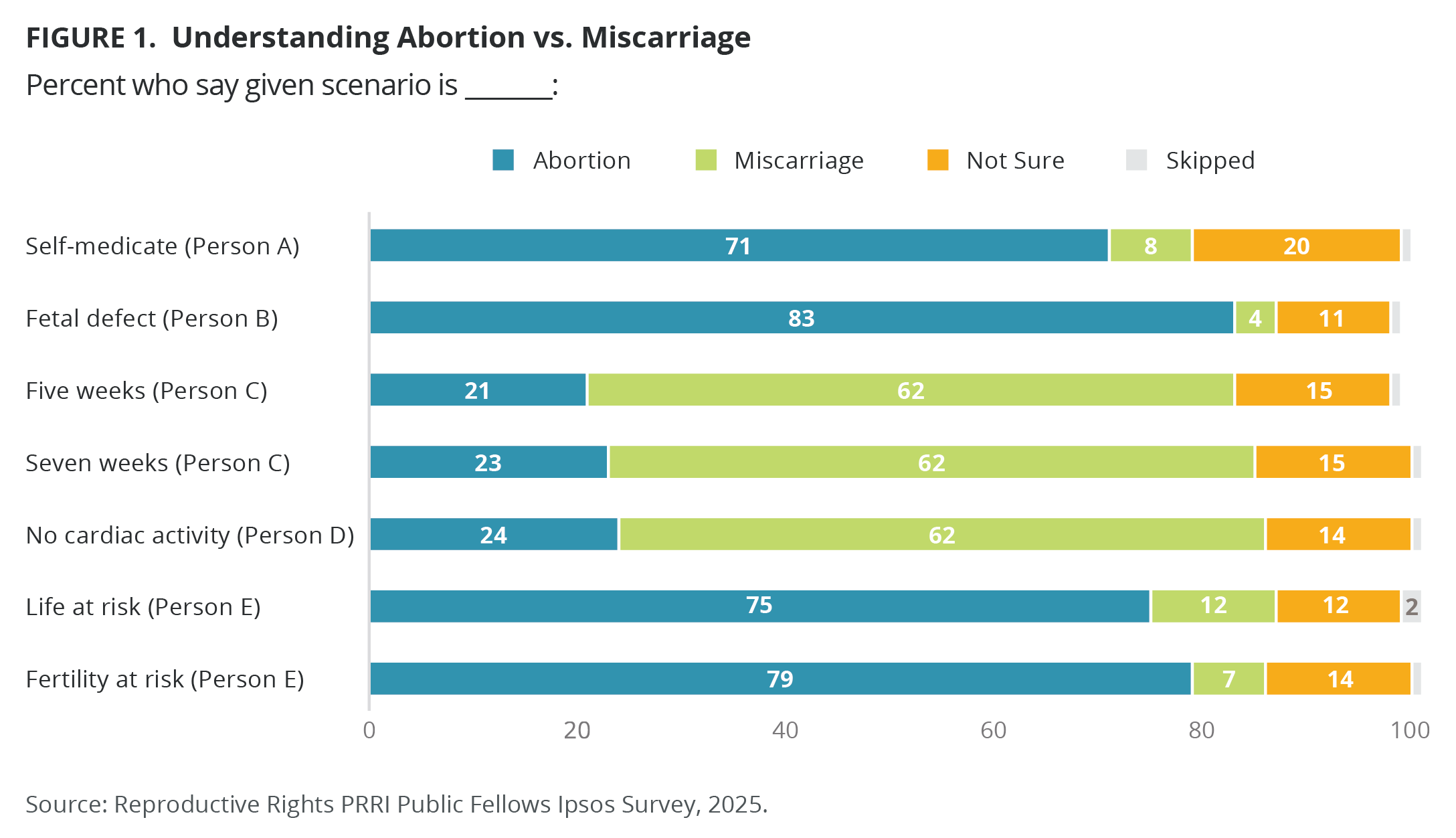

The survey results demonstrate there is significant confusion about what constitutes an abortion and what defines a miscarriage. Most survey respondents accurately identified the difference between an abortion and a miscarriage according to medical criteria. Yet, for each vignette, anywhere from 10% to 20% of respondents answered that they were not sure whether something was an abortion or a miscarriage. Consider Person C, who had a miscarriage at five or seven weeks. The vast majority of miscarriages happen in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, and miscarriages make up approximately 15% of all known pregnancies. A miscarriage at five or seven weeks is common, but 15% of our respondents were not sure what to call this.

In some scenarios, a significant percentage of respondents were wrong in their assessment. For Person C, over 20% wrongfully classified this scenario as an abortion, and nearly one-quarter of survey respondents classified removing a fetus with no cardiac activity (Person D) as an abortion. People were more likely to erroneously classify something as an abortion than to erroneously classify something as a miscarriage.

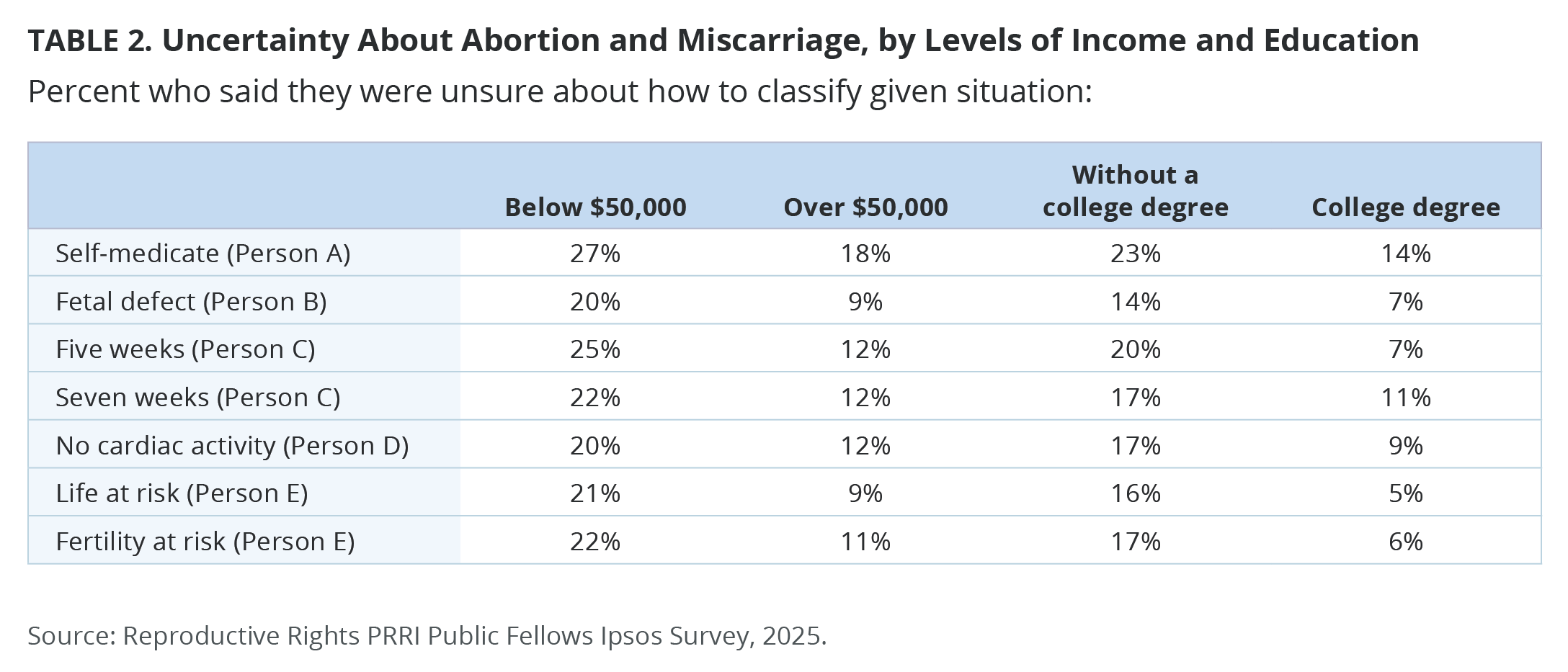

Religious identity does not seem to influence how participants classified the vignettes, but education and income level do. Respondents who were not sure tended to be less educated and have lower incomes than those who were confident about their answers. For example, uncertainty ranged from 20% to 27% among those earning under $50,000, compared with 9% to 18% among those earning over $50,000. Similarly, among those without a college degree, uncertainty ranged from 14% to 23%, while it ranged from 5% to 14% among those with a college degree.

The first conclusion we can draw from these findings is that the confusion around whether something is an abortion or a miscarriage reflects Americans’ lack of scientific literacy. Americans’ understanding of biomedical science has worsened in light of the politicization of medical care, particularly in reproductive medicine. Emotionally charged rhetoric used by abortion opponents, including “heartbeat bill” and “unborn child,” shifts the focus away from the health and medical care of the pregnant person.

Additionally, it is noteworthy that people were more likely to classify something as an abortion when it is biomedically a miscarriage than the other way around. While abortion stigma often leads people to underreport abortions by classifying their own experiences as a miscarriage to avoid negative judgment, that does not seem to be the case here. Perhaps these scenarios were the most confusing. Or maybe respondents viewed them as abortions because the law defines them as illegal. Another way of understanding this data is that the legal and cultural context in the United States today has stigmatized all reproductive experiences, to the point where our respondents label common miscarriages as abortions.

All told, the public is confused about reproductive experiences and suffering the consequences.

Three Years After Dobbs, Americans Are Unsure About Legality of Abortion

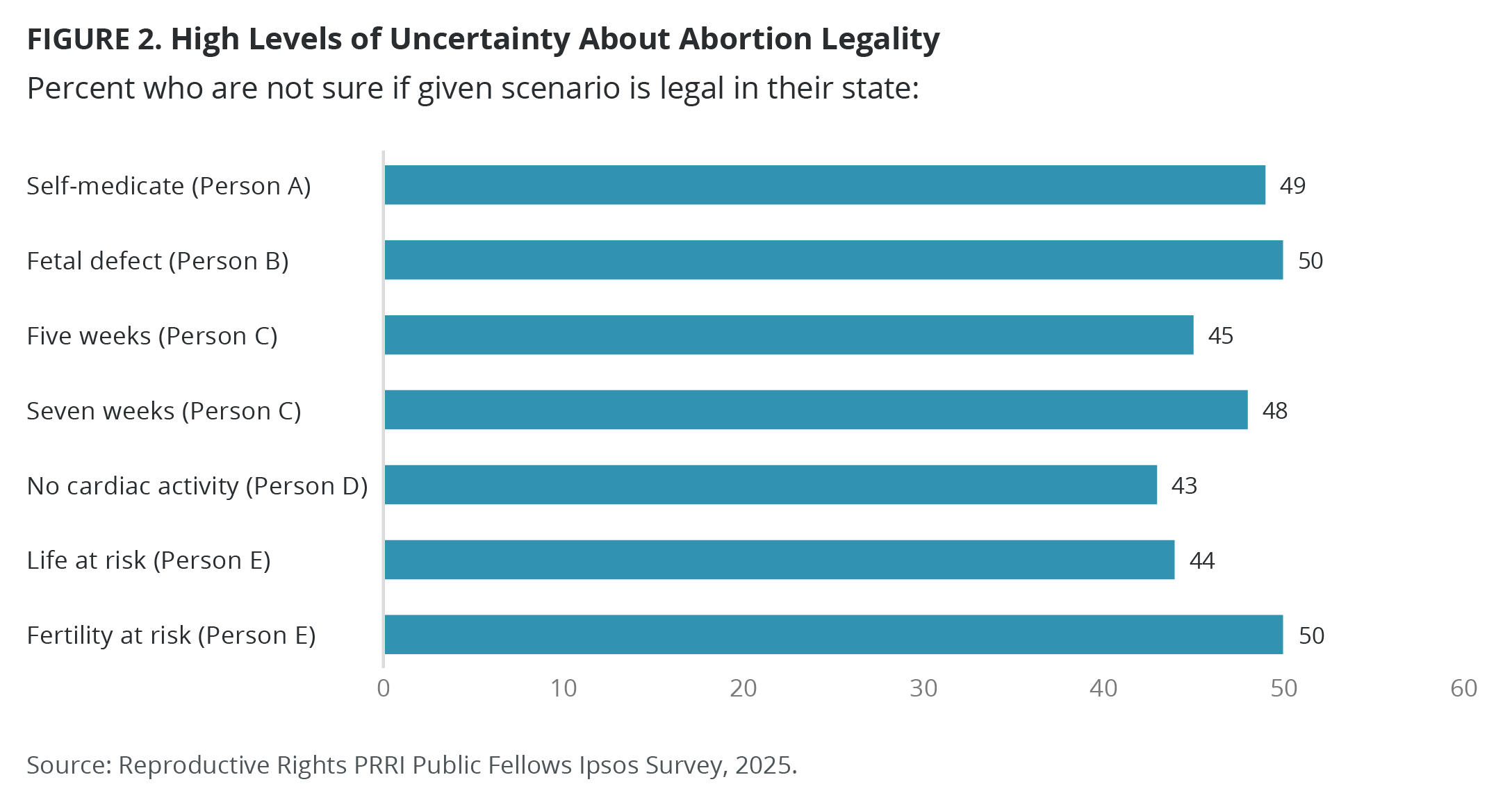

In addition to asking participants to classify example scenarios as either an abortion or a miscarriage, we also asked them to tell us whether they thought each scenario was legal in their state. After reading each vignette, 40% to 50% of respondents said they were not sure about the legality of the procedure described.

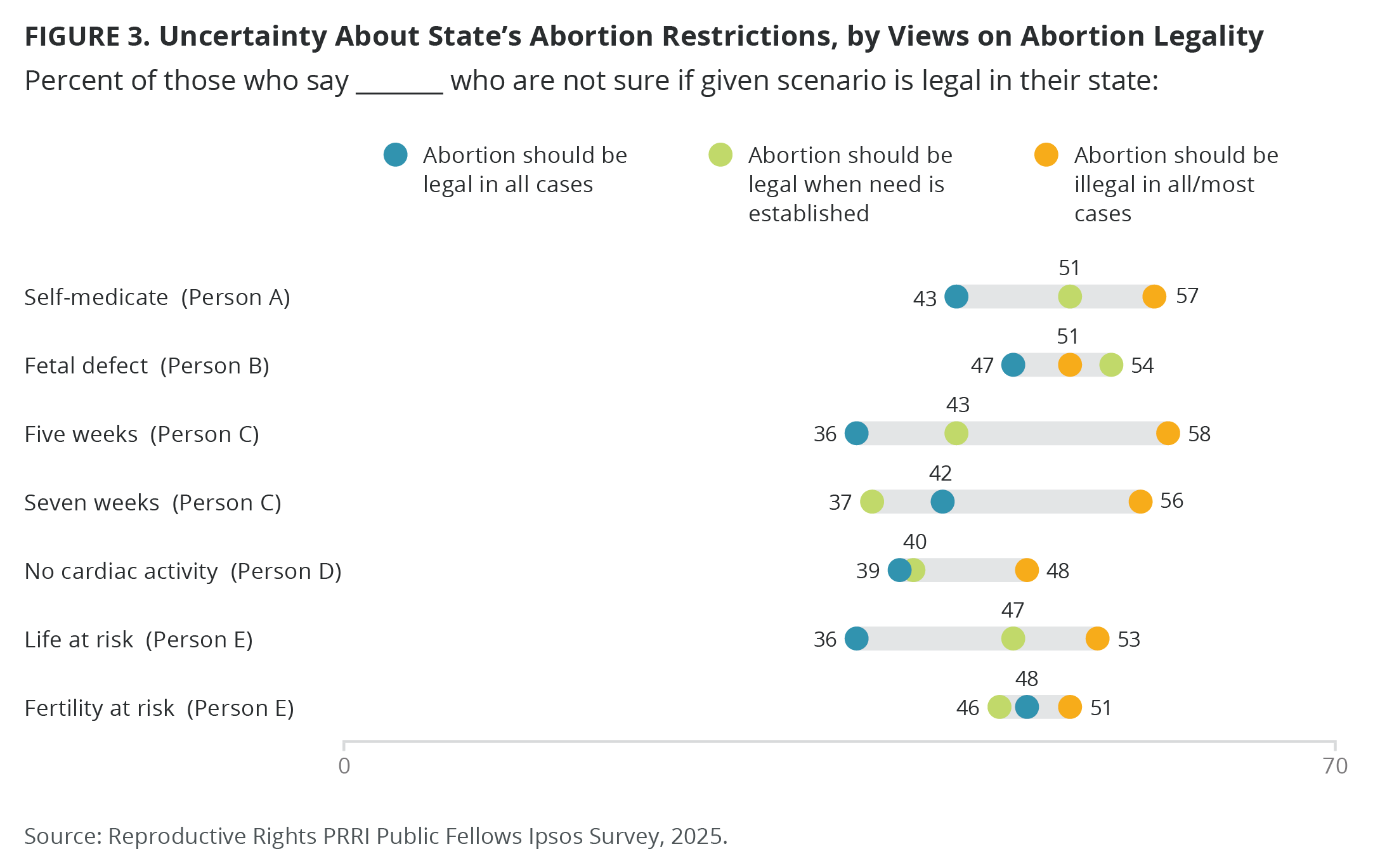

While education and income affected these answers similarly, at least 25% were not sure of the legality of certain procedures, even among respondents who graduated college and are making more than $100,000 a year. Further, in some cases, respondents who are opposed to abortion were less likely to know whether a scenario is legal in their state. More than half of those who say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases were not sure of the legality of using medication to manage a miscarriage at five weeks (58%). In contrast, just over one-third of those who support the legality of abortion in all or most cases were not sure (36%).

In another scenario, a 20-week ultrasound scan reveals a non-fatal fetal anomaly. The couple goes to the clinic to “have surgery to end the pregnancy.” This is precisely the type of scenario banned in many states, yet 51% of those who believe abortion should be illegal in all or most cases were not sure whether it was legal, compared with 46% of those who support the legality of abortion.

Living in a state with a strict abortion ban increases confusion. Approximately 60% of respondents in states where abortion is banned were unsure about the legality of using pills to manage a miscarriage at five or seven weeks. In contrast, fewer than 40% of respondents in states with no gestational limit were unsure about the legality of that scenario. Across all vignettes, participants in states where abortion is banned or where there is a ban before 22 weeks were unsure about the legality of more scenarios than participants living in states with fewer restrictions.

If the intention of some of these state laws and exemptions is to create confusion among the public and medical providers, they are succeeding. Women and other pregnant people are not seeking out medical care for miscarriages and abortions because they do not know if they will be arrested for getting that care. Similarly, doctors are refusing to treat patients because they fear the legal risks of doing so. Women and other pregnant people who are refused abortion care and miscarriage management face negative health outcomes.

What Does This Mean?

Based on this research, we have several suggestions to help people navigate this overwhelming legal context.

First, legislators should clarify the laws that exist in their states. State abortion bans are often accompanied by a confounding list of exceptions, but people clearly do not know whether any of the scenarios described in these research vignettes qualify as an exception. Confusion over these laws, and in particular whether certain fetal or maternal health diagnoses qualify as an exemption to the ban, has resulted in lower abortion rates in states with abortion bans (though importantly, not in the national rate of abortions), and resulted in poor maternal health care and higher rates of infant death.

Second, legislators should consult with medical experts when composing laws about health care. Abortion ban exceptions are often not applicable in real medical situations. Physicians are therefore unable to practice evidence-based medicine because of the unrealistic expectations of the law.

Third, states where abortion is legal should be more proactive about sharing this information with their residents. As we saw, even people living in states where abortion is legal are unsure whether these scenarios are legal. Many state legislatures have gone to great lengths to protect abortion rights, but if residents do not know if something is legal, they may be subject to undue anxiety in the middle of a health crisis, not to mention the financial and physical toll of traveling to another state to seek care that is available in their own state.

Finally, local news coverage should follow abortion regulations more closely. While the rate of U.S. adults who pay attention to the local news has declined in recent years, and many public news stations are struggling with diminishing federal funding, this news is more important than ever. When there was one federal law about abortion, local news coverage paid less attention to the regulations on abortion in their state. Post-Dobbs, we should be investing in local news organizations, and abortion access should be a focus of local news coverage to educate the public on its legality in their state.

About the Study

The study was designed by Michal Raucher, Ph.D., and Anne Whitesell, Ph.D., and conducted May 9-11, 2025 by Ipsos using its large-scale, nationwide, online research panel, KnowledgePanel, among a weighted national sample of 1,030 adults 18 or older living in all 50 US states and the District of Columbia. The margin of sampling error for the full sample is ±3.3 percentage points including a design effect of 1.15.

The data for the total sample were weighted to adjust for gender by age, race/ethnicity, education, Census region, metropolitan status, and household income using demographic benchmarks from the 2024 March Supplement of the Current Population Survey (CPS). Party ID benchmarks are from the 2024 National Public Opinion Reference Survey (NPORS).

Specific categories used were:

- Gender (Male, Female) by Age (18–29, 30–44, 45-59 and 60+)

- Race/Hispanic Ethnicity (White Non-Hispanic, Black Non-Hispanic, Other, Non-Hispanic, Hispanic, 2+ Races, Non-Hispanic)

- Education (Less than High School, High School, Some College, Bachelor or higher)

- Census Region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West)

- Metropolitan status (Metro, non-Metro)

- Household Income (Under $25,000, $25,000-$49,999, $50,000-$74,999, $75,000-$99,999, $100,000-$149,999, $150,000+)

- Party ID (Republican, Leans Republican, Independent/Other, Democrat, Leans Democrat)

The study was approved by the Rutgers University Institutional Review Board.

– “The Border Informs My Faith”: Oral History Methodologies and Understanding Immigration Politics Among People of Faith in Arizona

– Faith, Freedom, and the Future of LGBTQ Rights in America

– Democracy Today: Insights on Race, Religion, and Democratic Principles

– Why Are All the Black Christians Choosing to Go to Church Together?