During his 2016 Republican National Convention nomination acceptance speech, former President Donald Trump stated: “Only weeks ago, in Orlando, Florida, 49 wonderful Americans were savagely murdered by an Islamic terrorist. This time, the terrorist targeted our LGBT community. As your President, I will do everything in my power to protect our LGBT citizens from the violence and oppression of a hateful foreign ideology.” In making this claim, Trump constructed Muslims as being at odds with LGBT rights, arguing that he was the best candidate because former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton was soft on Muslim immigration. This comment exemplifies how some politicians, notably on the religious right, have capitalized on the “homophobic Muslim boogeyman” to intimidate voters.

This framing incorrectly assumes Muslim homophobia and ignores LGBT members of the Muslim community. In contrast to the stereotype, there has been a rapid and growing acceptance of LGBT rights among the U.S. Muslim population. The Pew Research Center found in a 2017 survey that more than half of American Muslims (52%) agreed with the statement, “Homosexuality should be accepted by society,” up from 27% (and nearly double) from their 2007 survey a decade prior. And, more recently in 2021, PRRI’s American Values Atlas found that 75% of Muslims agreed that “Laws that would protect gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people against discrimination in jobs, public accommodations, and housing.”[1]

Despite this positive turn, we know very little about LGBT members of the Muslim population, as more research is needed. Understanding better who they are, the strength of their LGBT and Muslim identities, and with whom they have shared their LGBT status, will allow scholars to paint a more comprehensive picture of the U.S. Muslim population, while dispelling the notion that LGBT Muslims cannot identify as both Muslim and LGBT. While some work has evaluated diversity among U.S. Muslims, paying special attention to the role of religiosity, gender and the hijab, and race, we know less about gender identity and sexuality because it is difficult to draw survey samples that represent both Muslim identity and LGBT identity together. Without these data, it is easy to make the incorrect assumption that being Muslim is a fixed identity and that people cannot be both LGBT and Muslim.[2]

Our research addresses this gap. Drawing from the 2020 Collaborative Multiracial Post-election Study (CMPS), which surveyed 581 Muslims, we pay specific attention to LGBT Muslims. This survey is the first to oversample multiple minoritized social groups, such as Muslims and LGBT people in the United States, and ask detailed questions of them. Notably, this sample differs from a nationally representative sample of Muslims.[3] The Pew 2017 survey provides the most up-to-date estimates of what comes closest to a nationally representative sample of U.S. Muslims. The Pew report indicates that 21% of Muslims are converts, 40% are over the age of 40, 20% identify as Black, and 82% are citizens. Here in the 2020 CMPS, 20% of the sample are converts, 30% are ages 40+, 27% identify as Black, and 83.5% are citizens. Thus, while both samples are similar in terms of citizenship, the CMPS sample is younger and more diverse than the U.S. Muslim population.

In the study, which was conducted on a convenience sample of Muslims, 64 people (11%) identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgender.[4] In what follows, we provide some descriptive information about this population and three key takeaway points for researchers and advocates.

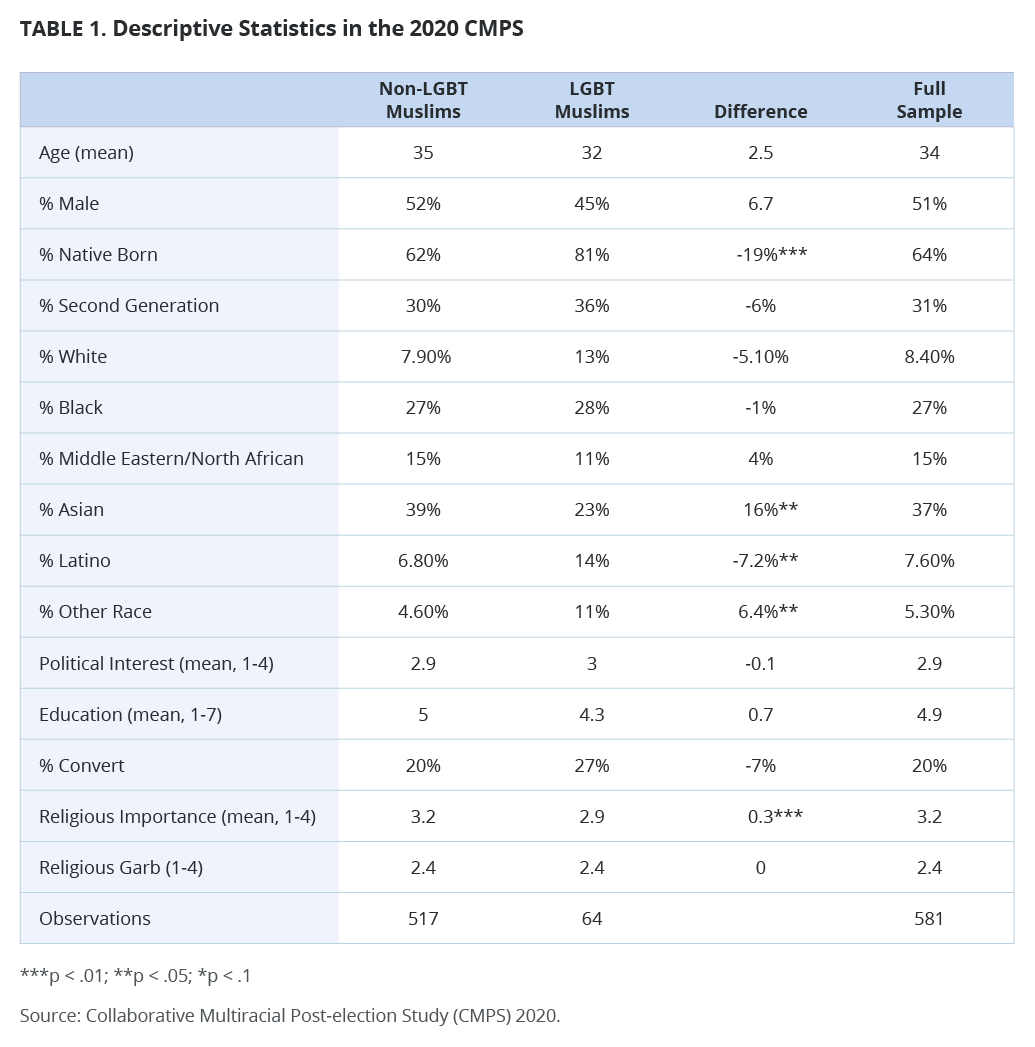

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics about the non-LGBT and LGBT subsets of Muslim respondents in the survey. Despite the small sample sizes, significant differences between the non-LGBT and LGBT Muslim respondents emerge along the lines of nativity, religious importance, and race.

First, there are important demographic differences among LGBT Muslims. On average, LGBT Muslims are more native born, less Asian, more Latino, more other race, and slightly less likely to indicate that religion was an important part of their daily lives.

Second, LGBT Muslims are more likely than not to share this important part of their lives with people in their lives. The survey also asked respondents who identified as lesbian, gay, or bisexual who they had “come out” to in their lives. While 22% of the 55 respondents who answered these questions had not come out to anyone in their lives, a larger percentage shared their gender and sexual identities with the people in their lives: 58% had come out to their friends, 38% had come out to their families, 34% had come out to their co-workers, and 31% had come out on social media. About one in four LGBT American Muslims (24%) had come out to everyone in their lives.

Moreover, when asked how important religion was in their lives, both LGBT Muslims and non-LGBT Muslims care about religion at similar rates. The survey asked respondents the following question: “How important is religion in your life – (4) very important, (3) somewhat important, (2) not too important, or (1) not at all important?” Over 70% of LGBT Muslims stated that religion was either somewhat or very important in their lives, while around 79% of non-LGBT Muslims agreed. Moreover, the groups were not significantly different in levels of agreement. These findings indicate that religious importance and LGBT identity do in fact coexist, presenting an important challenge to the rhetoric that Trump and other politicians have openly espoused.

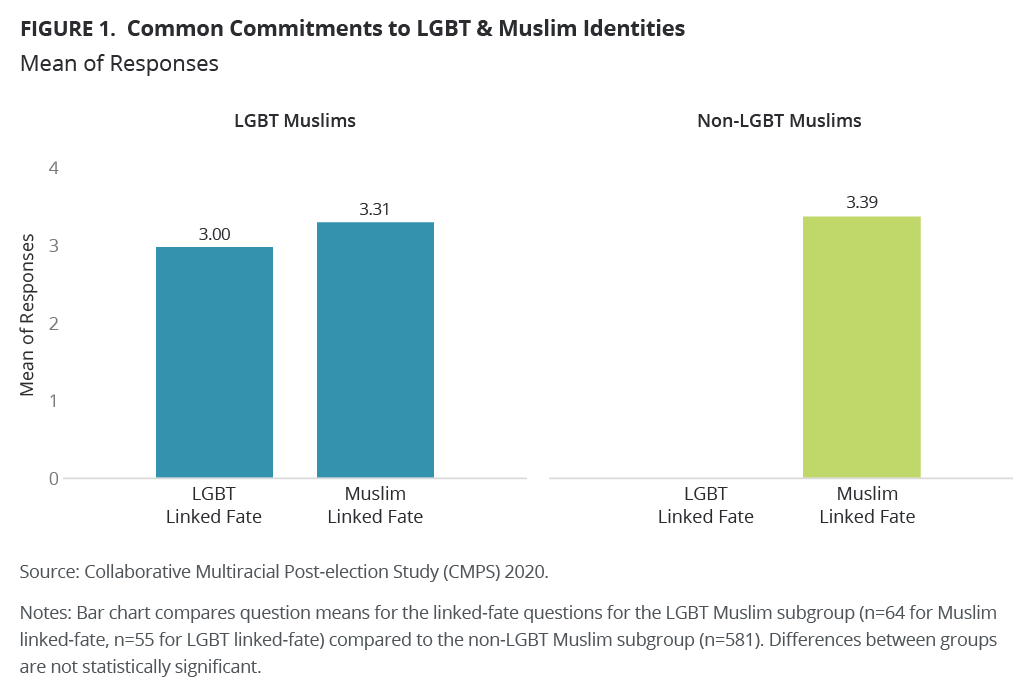

Finally, LGBT Muslims in our sample were equally attached to their LGBT and Muslim identities— attachment to one doesn’t preclude attachment with the other. All Muslim respondents were asked a linked-fate survey question: “How much do you think what happens to Muslim people here in the U.S. will have something to do with what happens in your life?” In addition, most LGBT Muslims (n=55, out of 64) were asked an LGBT linked-fate question: “How much do you think what happens to gay, lesbian, queer people in this country will have something to do with what happens in your life?” Response options to both questions varied on a scale of 1-5 ranging from “Nothing to do with what happens in my life” (1) to “A huge amount to do with what happens in my life (5).

Turning first to the Muslim linked-fate question, on average, all Muslims in the sample scored 3.39 (n=581), while LGBT Muslims scored 3.31 (n=64), a non-statistically significant difference. Next, turning to the LGBT linked-fate question, on average respondents scored 3.0, a non-statistically significant difference from their Muslim linked-fate question (3.31). This suggests that LGBT members of the Muslim community hold concurrent, politicized group identities.

Together, our findings shed more light on the LGBT Muslim population. They demonstrate that a non-negligible portion of the U.S. Muslim population identifies as LGBT. Moreover, they show that LGBT Muslims are equally attached to their LGBT and Muslim identities, challenging the notion that attachment to these identities is mutually exclusive. And, they contest the idea that Muslim homophobia is rampant. Many LGBT Muslims are out to their family, friends and the public. While it is widely assumed that LGBT Muslims cannot be both attached to their Muslim and LGBT identities, very little evidence has been brought to bear on this question, and the evidence here dispels this paternalizing myth

Nazita Lajevardi, Evan Stewart, Roy Whitaker, and Tarah Williams are members of the 2021-2022 cohort of PRRI Public Fellows.

Footnotes

[1] Though small in sample size (n=89), this survey also found that 77% of Muslims in the sample disagreed with “Allowing a small business owner in your state to refuse to provide products or services to gay or lesbian people, if doing so violates their religious beliefs.

[2] Notably, some scholarship has identified strategies that LGBT Muslims employ for reconciling the cultural and political tensions that exist when one holds both a LGBT and Muslim identity.

[3] We do not know the true size and composition of the U.S. Muslim population because the Census does not ask questions on religion. For a more detailed discussion, see Hobbs and Lajevardi (2019), p. 271. Nonetheless, PRRI estimates that Muslims compose 1% of the U.S. population.

[4] In total, 20 people indicated they are transgender. Of those, 11 also indicated they were either lesbian, gay, or bisexual.