Over the past two years, government officials in a number of states have introduced new policies to limit or prohibit certain types of conversations about race and gender in diversity trainings or educational institutions. Officials have often mentioned Critical Race Theory (CRT) in the text of these bans or in discussions about why they were introduced. CRT, which was developed and taught in law schools, centers in part on the idea that race is an invented cultural category used for oppression and that the law and legal institutions in the U.S. are inherently racist, as they are used to perpetuate racial inequalities. The CRT Forward Tracking Project, created by the Critical Race Studies program at UCLA School of Law, reports that as of Oct. 6, 2022, there have been 523 endeavors “aimed at restricting the ability to speak truthfully about race, racism, and systemic racism through a campaign to reject Critical Race Theory.”

Bans on Critical Race Theory are largely a response to “The 1619 Project,” a series released in 2019 which “aims to reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans at the very center of the United States’ national narrative.”[1] Its title comes from the year that the first enslaved Africans were brought to North America. The series argues that 1619 should be considered the starting point of American history and that slavery must be considered a core part of the nation’s roots. Educational materials designed to be used in K-12 schools were released to accompany the series.

Many politicians have opined that teaching these materials would be harmful and divisive for the nation. Then-President Donald Trump even issued an Executive Order in November 2020 in which he said versions of history that “vilified” the founders could “fray and ultimately erase the bonds that knit our country and culture together” and that focusing on historic racism “would place rising generations in jeopardy of a crippling self-doubt.”

However, despite widespread efforts to curb discussions about racism and gender discrimination, recent surveys suggest that the majority of Americans disagree with at least some aspects of these bans.

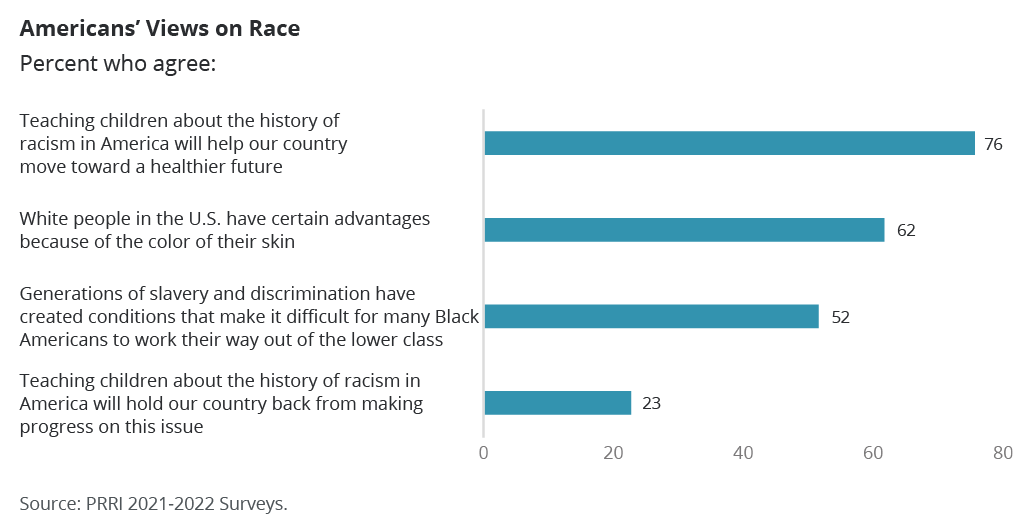

In August 2021, PRRI surveyed of a representative sample of more than 5,400 adults living across the United States (see questions #11a and #11b on the survey topline). About three in four Americans (76%) agreed that “Teaching children about the history of racism in America will help our country move toward a healthier future.”[2] However, many anti-CRT laws (such as those adopted in Georgia and Tennessee, as well as bills that did not pass in Florida, Virginia and Louisiana) contain clauses prohibiting diversity trainings and educational activities focused on racism and sexism, on the grounds that they are “divisive” concepts. Some statutes, including the one in Tennessee, also state that CRT is “contrary to the unity of the United States of America and the well-being of this state and its citizens.”

The survey also revealed that about three in four Americans (76%) disagreed (29% somewhat, 47% completely) with the statement “Teaching children about the history of racism in America will hold our country back from making progress on this issue,” further suggesting that public opinion is at odds with anti-CRT policies.[3] Specifically, some anti-CRT policies limit the ways that the history of racism can be described. For instance, a bill passed in Texas prohibits teaching that the start of slavery in the colonies “constituted the true founding of the United States” or that “slavery and racism are anything other than deviations from, betrayals of, or failures to live up to the authentic founding principles of the United States, which include liberty and equality.”

Other recent surveys suggest public opinion is also at odds with other parts of anti-CRT policies. When PRRI asked in June 2022 how Americans feel about the statement “Generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for many Black Americans to work their way out of the lower class,” a slight majority agreed (52%), a significant increase from 41% in 2015, when the question was first asked. Additionally, in the same June 2022 survey, 62% of Americans agreed that “White people in the U.S. have certain advantages because of the color of their skin” — roughly the same as the percentage in 2018 (61%).

Although most survey participants said they believe that racism still impacts Black Americans and that white people enjoy certain privileges because of their race, anti-CRT laws contain numerous clauses prohibiting teaching about privilege and racism. For instance, they almost universally prohibit teaching that an individual has inherent privileges because of race or sex (this is true in the Florida, Georgia, and Tennessee laws mentioned above). Many also contain clauses to prohibit teaching that the United States is fundamentally racist or sexist (this is true in Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, Virginia, and Louisiana, as noted earlier) or teaching that the assertion that all Americans are created equal and endowed with equal rights has not held true for everyone (Tennessee’s law says this, for example). Such discussions of race- or gender-based privilege or status are not only prohibited but are often denounced in these laws as “race or sex stereotyping” (including in the laws in Florida, Tennessee, Georgia, and Louisiana).

[1] The 1619 Project was developed by The New York Times under the leadership of Nikole Hannah-Jones.

[2] This question was only asked of half the sample

[3] This question was only asked of half the sample

Danielle N. Boaz is a members of the 2022-2023 cohort of PRRI Public Fellows.