As the 20th anniversary of 9/11 came and went last year, much has been written and discussed on the impacts of the attacks. Twenty years later, much of this impact is still being felt, particularly in Muslim, Arab, and South Asian communities. People in these communities are often seen as suspects or perceived as dangerous or terrorist threats by American government and the larger U.S. population.

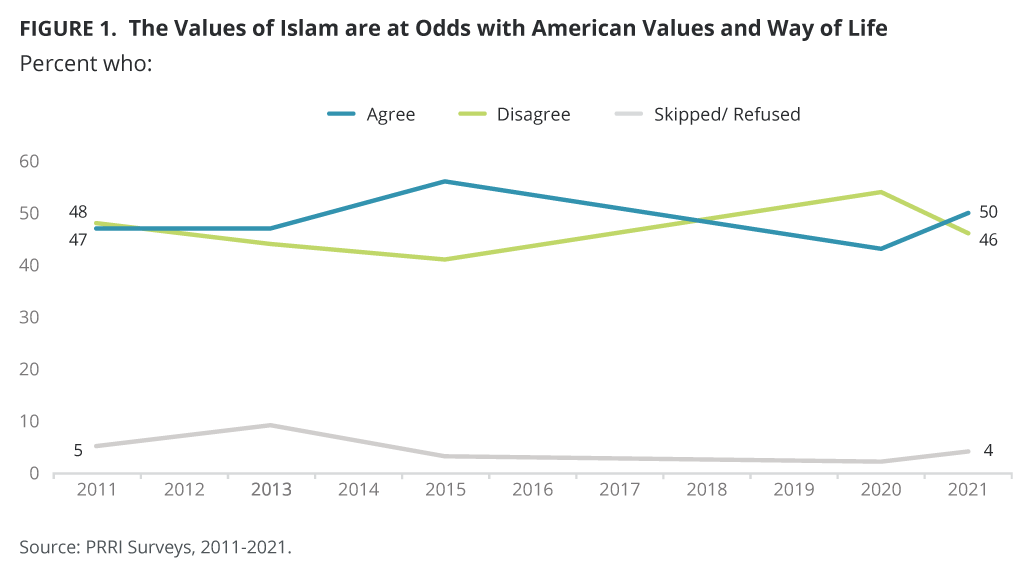

This suspicion of Muslims has been reflected in opinion data collected by PRRI. For example, 50% of respondents agreed with the statement, “The values of Islam are at odds with American values and way of life,” in September 2021. This percentage of respondents has increased since September 2011, when 47% of respondents agreed with this statement.

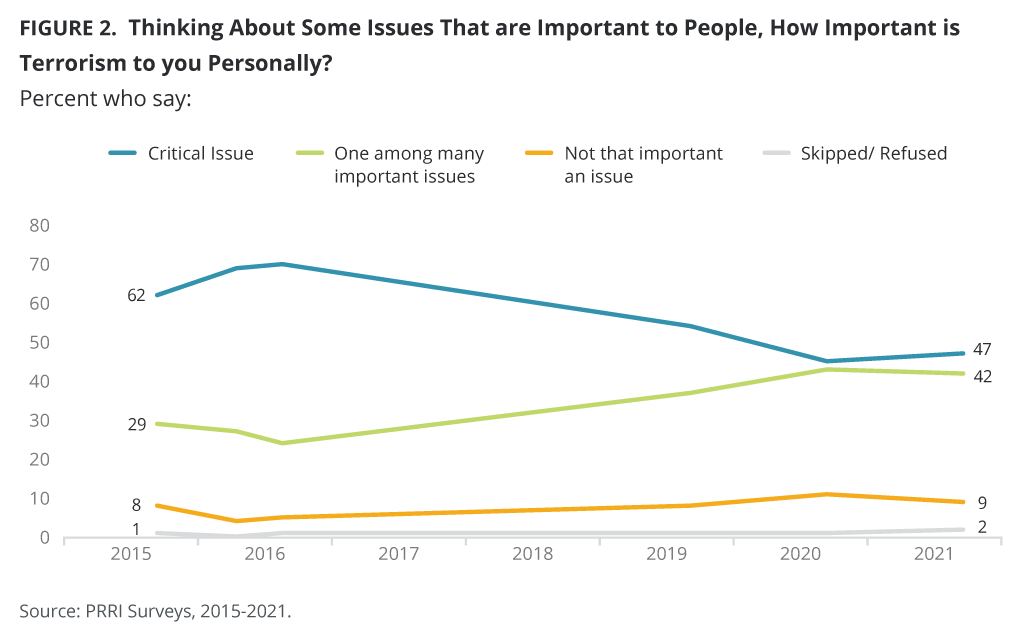

In a question from 2015, respondents were asked about the most important reason that the United States should not allow refugees from Syria, a Muslim-majority country, to enter. PRRI data found 57% of respondents indicated that Syrians represent a threat to national security. This is especially pertinent since terrorism is still thought of as a critical issue in the United States. Nearly half of respondents in September 2021 (47%) thought of terrorism as a critical issue, while 42% of respondents thought it was an issue among many others. While the view of terrorism as a critical issue has dropped since October 2015, from 62%, over 80% of respondents still worry about terrorism as a critical issue or one among many issues in 2021.

Thinking of Muslims as anti-American is troubling on its own, but this is exacerbated by how Muslim communities undergo continued surveillance. This is exemplified by the March 2022 U.S. Supreme Court decision FBI v. Fazaga. In 2006, a fitness instructor, Craig Monteilh, was recruited by the FBI to serve as an informant. His task was to attend the Islamic Center of Irvine, California, where he pretended he was a convert in order to gather information on other attendees. The FBI called the program Operation Flex, which involved Monteilh offering to work as a fitness instructor for members of the Muslim community in order to get close to them. He recorded conversations with Muslims for over a year, where he stated his aim was to identify militants and other potential informants, like those who were having clandestine affairs or were LGBTQ, to the FBI.

Thinking of Muslims as anti-American is troubling on its own, but this is exacerbated by how Muslim communities undergo continued surveillance. This is exemplified by the March 2022 U.S. Supreme Court decision FBI v. Fazaga. In 2006, a fitness instructor, Craig Monteilh, was recruited by the FBI to serve as an informant. His task was to attend the Islamic Center of Irvine, California, where he pretended he was a convert in order to gather information on other attendees. The FBI called the program Operation Flex, which involved Monteilh offering to work as a fitness instructor for members of the Muslim community in order to get close to them. He recorded conversations with Muslims for over a year, where he stated his aim was to identify militants and other potential informants, like those who were having clandestine affairs or were LGBTQ, to the FBI.

After not finding any suspicious activity, he tried to entrap Muslims by talking about his interest in jihad and a desire to martyr himself. These comments led Muslims to report Monteilh to the FBI for his suspicious behavior. The imam of the mosque, Yassir Fazaga, along with two other members of the community, eventually filed a class action lawsuit against the FBI in 2011 for spying on them, claiming religious discrimination.

The district judge blocked the civil suit, claiming that if the FBI were sued, it would have to reveal privileged information that could compromise national security. Fazaga appealed the decision and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit partially reversed the decision, allowing for the civil suit to proceed. In June of 2021, the case made its way up to the Supreme Court, which unanimously voted to reverse the Court of Appeals ruling, siding with the FBI. As a result of this Supreme Court case, the FBI is protected from litigation by Muslims for its tactics, leaving Muslims vulnerable to discriminatory policing and surveillance.

The association of Muslims with terrorism and the belief that they are a potential threat to national security has consequences. And while PRRI data shows that 53% of Americans opposed temporarily banning Muslims from coming to the United States, which was reflected in multiple protests that occurred when former President Donald Trump signed an executive order banning individuals from seven Muslim-majority countries, there has been little public outcry or media coverage on FBI v. Fazaga. Cases like this reflect the public’s attitudes toward Muslims and a general lack of concern about their civil rights. Twenty years after 9/11, we need more accountability for discriminatory policing and surveillance practices, and transparency of our counterterrorism programs.

Luis Romero and Saher Selod are members of the 2021-2022 cohort of PRRI Public Fellows.