Dr. Dara Coleby Delgado is the Bishop James Mills Thoburn Chair of Religious Studies, an Assistant Professor of History and Religious Studies, an affiliate faculty in Black Studies and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Allegheny College and a 2023-2024 PRRI Public Fellow.

During a 2022 CBS interview, far-right, celebrity pastor Greg Locke was asked if he believed “racism is baked into the structure of America.” Before the interviewer could finish the sentence, Locke responded, “No.” Exacerbated, Locke continued, “They want us to think that, but I don’t think we do. That’s what these social justice churches are. They’re picking a scab, picking the scab… and they won’t let us heal because they keep bringing it up…” While unsurprising, Locke’s response contradicts the dominant public-facing position of some popular contemporary evangelical Christian churches and para-church ministries and their obsession with moving toward superficial “racial reconciliation.”

Arguably, white evangelicalism’s ongoing efforts towards racial reconciliation are another iteration of what Michael Harriot for The Grio recently identified as race-baiting in the political sphere. Harriot does not refer to racial reconciliation, but his analysis can help us understand white evangelicalism’s obsession with promoting a colorblind, post-racial society. Moreover, it offers insight into why proponents of racial reconciliation have little use for the contemporary interest in Juneteenth.

Historically, Juneteenth — which became a federal holiday in 2021 — marks the emancipation of Black enslaved persons in Texas in 1865. Still, the Black experience since then has been marked by the ongoing struggle for liberation in a so-called Christian nation that holds immense disdain for social justice and is equally bothered by overt efforts toward civil and human rights. This Spotlight explores white Christian Americans’ attitudes about racial justice, in light of these contradictions.

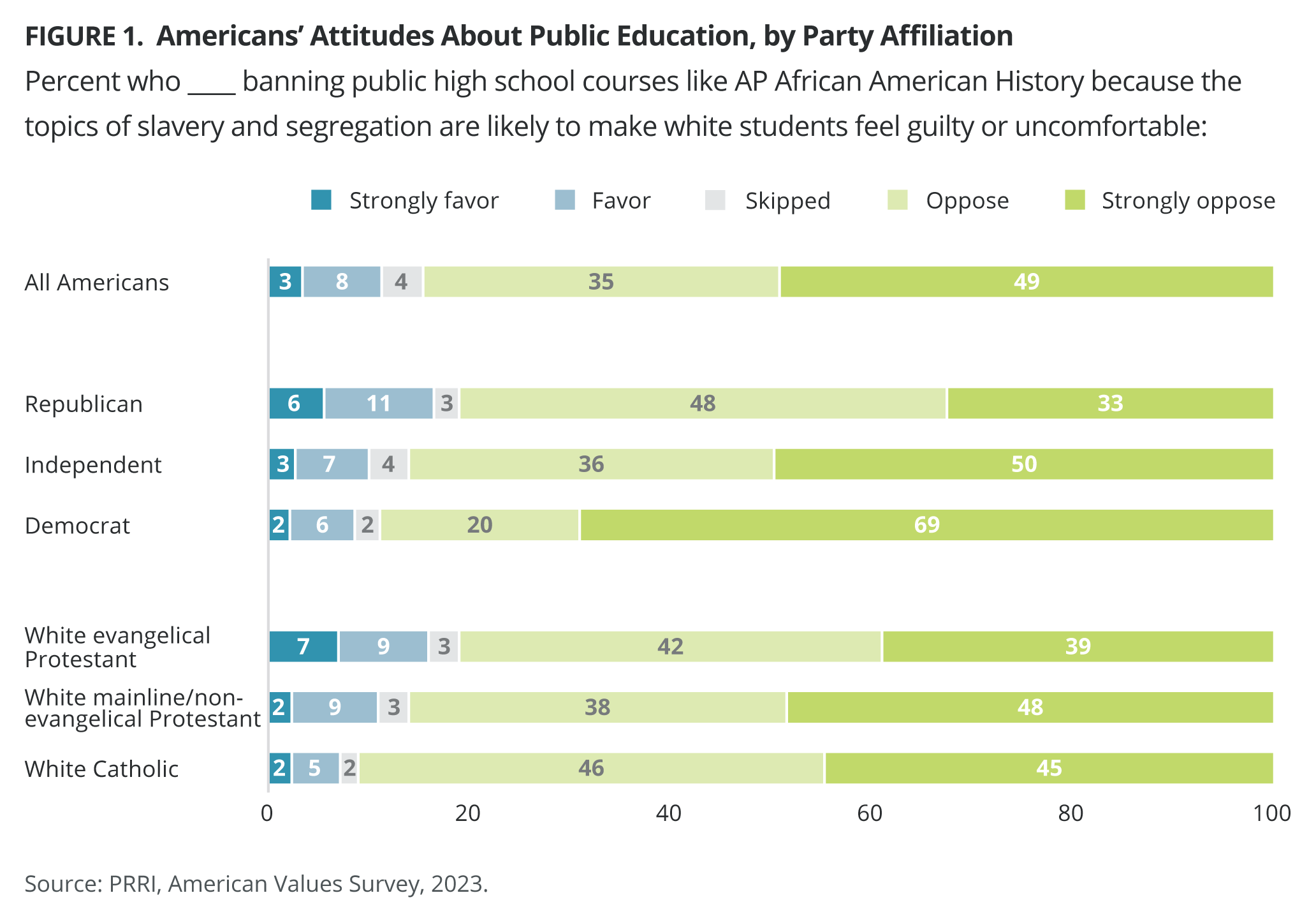

In October 2023, PRRI and the Brookings Institution published the 2023 American Values Survey (AVS). The survey yielded important insights into Americans’ attitudes about racial justice and racial reconciliation today. Concerning bans on teaching African American/Black History in public schools, the survey found “about one in ten Americans (11%) favor banning high school courses like AP African American History because the topics of slavery and segregation are likely to make white students feel guilty or uncomfortable, compared with 84% who oppose such bans. Republicans (17%) are more likely than independents (10%) and Democrats (8%) to favor banning these courses.”

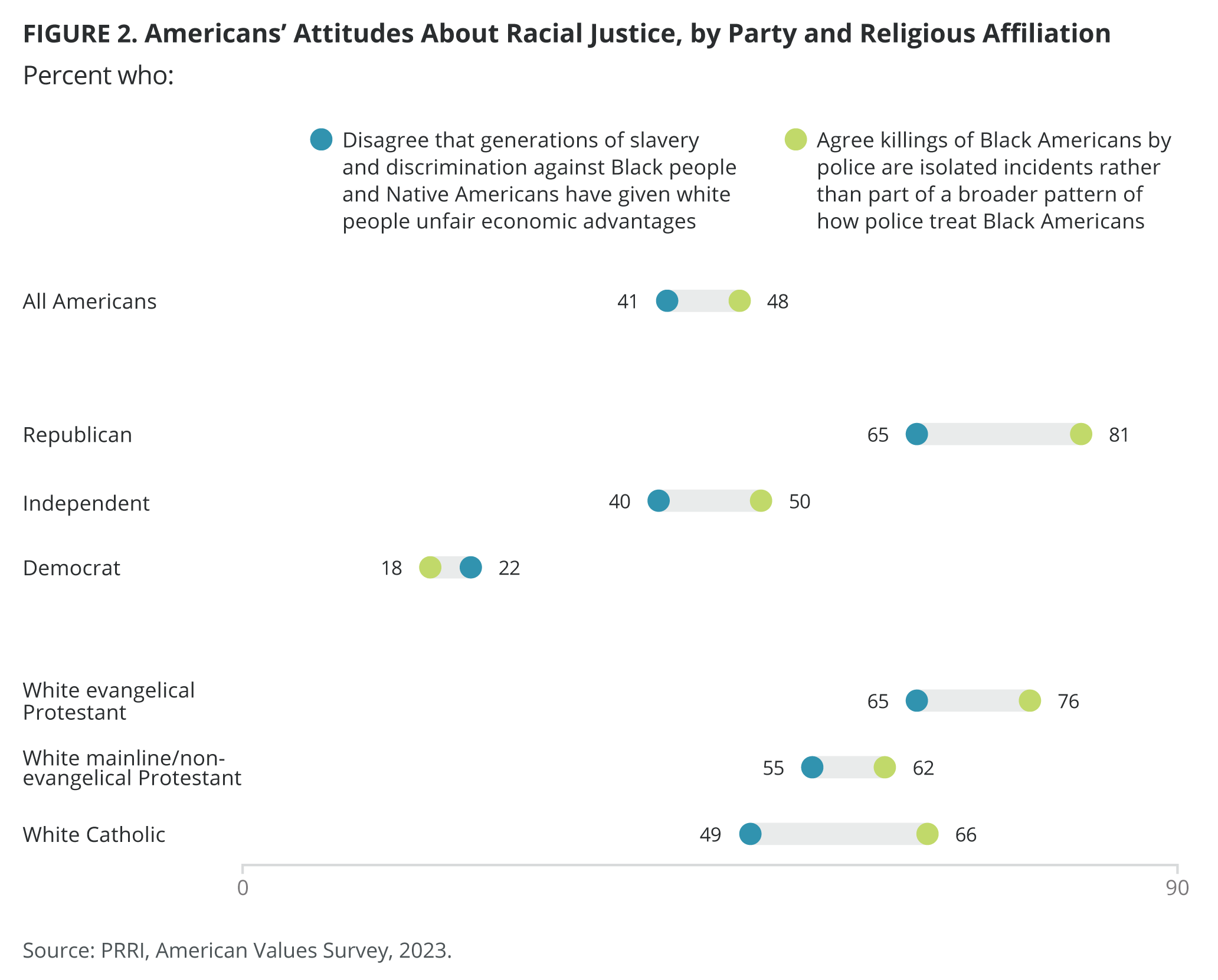

On questions about systemic racism, the survey found that 65% of Republicans disagree that ‘generations of slavery and discrimination against Black people and Native Americans have given white people unfair economic advantages.’ Even more interesting is that white Christian subgroups are significantly more likely than other religious groups to disagree with this statement — the breakdown: 65% of white evangelical Protestants, 55% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, and 49% of white Catholics disagree.

The study yielded similar trends when those surveyed were asked whether they felt Black American killings by police were isolated incidents or part of a broader pattern of anti-Black violence by police. Generally, since 2015, American attitudes have been divided on this issue. However, as of 2023, 81% of Republicans said that “killings of Black Americans by police are isolated incidents rather than part of a broader pattern of how police treat Black Americans.” Likewise, the majority of white Christians surveyed agreed that killings of Black Americans by police are isolated incidents.

Despite theological rhetoric about humanity existing in the image and likeness of God, most white American evangelicals’ attitudes are ambivalent, if not hostile, to these statements about racial justice. This explains, therefore, why we see many use vacuous ideas like racial reconciliation to, at best, turn a [color] blind eye to the precarity of Black Americans’ systemic oppression and, at worse, bait a segment of American religionists into believing that the full liberation of Black people is a bygone issue.

What does that mean for Juneteenth, beyond enjoying another day off while eating Walmart’s Celebration Edition Juneteenth ice cream? And what, if anything, are the implications for Black American Christian identities?

For one, Black forms of Christianity developed as a distinct religious expression among Black individuals in the United States as a reclamation of power, subjectivity, and personhood. Indeed, today we see notably distinct attitudes from Black Protestants compared with their white counterparts across the AVS’s questions on racial justice. For instance, just 13% of Black Protestants agreed that “killings of Black Americans by police are isolated incidents” compared with 76% of white evangelical Protestants and 62% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants.

Sadly, Juneteenth is not readily associated with Black religiosity or spirituality. This is unfortunate because Juneteenth’s liberationist ethos is emblematic of why Black religious institutions, especially the Black church, still exist as distinct repositories of Black culture, expression, and resilience that speak to Black Americans’ particular racial, spiritual, and socio-political needs.

Therefore, Juneteenth, like Black religious identities and expressions themselves, is as much a cultural marker for Black people believing as it is for Black people being — free from the white gaze or even threat. In the context of Black religious identities and expressions, which have always pushed back against racism, Juneteenth is a celebration of liberation without the added toll of Black people having to assuage white guilt, feign racial reconciliation, or validate white America’s belief in racism without racists.