The Majority of LGBT Americans Are Religious: Who They Are and Why They Matter

Americans have grown accustomed to hearing about tensions between those who support lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights and supporters of religious freedom. Though these two groupings may accurately represent how some voters see the conflict over these issues, they exclude the people caught in the middle of this debate: religious LGBT Americans.

Although ignoring the existence of religious LGBT Americans may facilitate a simpler political discussion, it is clearly not reflective of reality. The larger question is how far from reality is this discussion? From 2016-2019, the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) collected data from more than 280,000 Americans, including over 11,000 LGBT Americans.

The biggest takeaway from this data is that most LGBT Americans identify as religious (56%). Further, among those who identify as religious, a substantial minority (38%) identify with a religious tradition with denominational beliefs that discourage same-gender sexuality or diverse gender expressions.

Politically, religious LGBT Americans largely identify as a Democrat (43%) or independent (38%). However, they do so at lower rates than religiously unaffiliated LGBT Americans, among whom 44% are Democrat and 44% are independent. Although a minority of religious LGBT Americans identify as a Republican (14%), they are more likely to do so than unaffiliated LGBT Americans (6%).

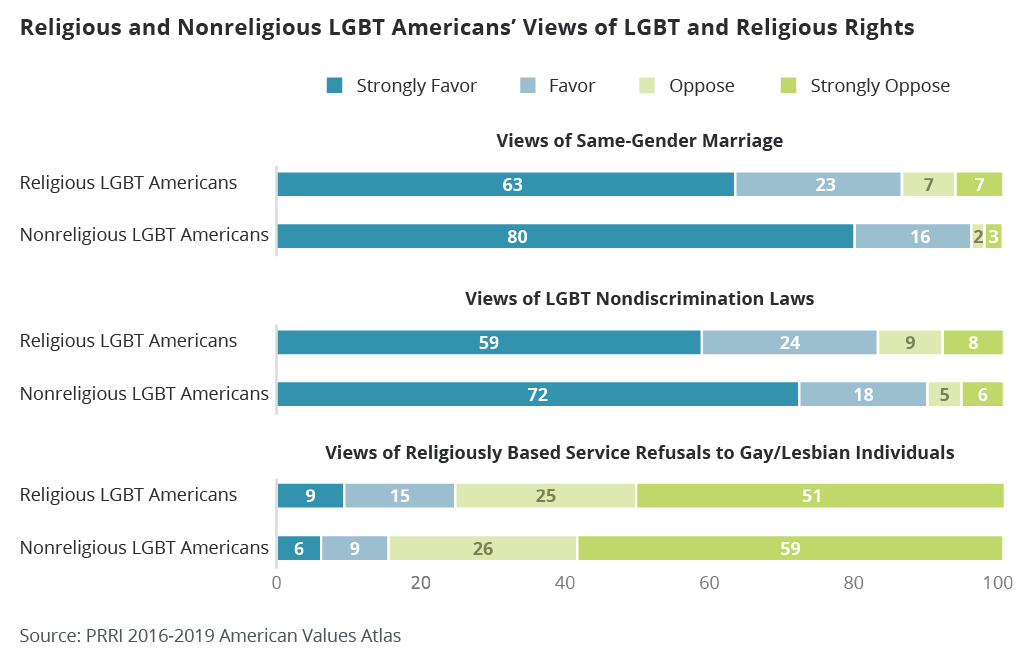

Religious LGBT Americans also differ substantially from their unaffiliated counterparts in their views about religion and LGBT rights. Specifically, religious LGBT Americans are less likely than unaffiliated LGBT Americans to strongly favor same-gender marriage (63% vs. 80%) and nondiscrimination laws (59% vs. 72%) and to strongly oppose religiously based service refusals (51% vs. 59%).

Taken together, these trends suggest that assuming LGBT Americans are inherently unaffiliated is quite far from the truth. In fact, most LGBT Americans identify as religious, and many of them identify with religious traditions that are often cast as anti-LGBT, such as Catholicism, Islam, and evangelical Christianity.

Religious LGBT Americans have their feet on both sides of the debate that puts religious freedom in conflict with LGBT rights. This may lead them to have more nuanced political views on these issues than their unaffiliated counterparts. Although most religious LGBT Americans clearly support LGBT rights, it appears that they are more likely to understand that there may be some give and take in rights, such as in the case of religiously based service refusals.

These trends do not tell us how to resolve contemporary debates about religious freedom and LGBT rights, but they do shed some light on how to engage with these topics. Particularly, they suggest that it is inaccurate to understand LGBT rights and religious freedom as existing on opposite ends of a single spectrum. Further, they suggest that instead of talking about religious LGBT Americans, we might learn important lessons of how to engage around these complex issues from religious LGBT Americans.