The Future of “Born-Again Evangelicalism” Is Charismatic and Pentecostal

Donald J. Trump’s most ardent, enthusiastic Christian supporters are arguably Pentecostal and charismatic. Televangelist Paula White-Cain, the president’s “personal pastor,” and a host of Pentecostal and charismatic celebrity supporters enthusiastically visited Trump’s White House, dominated his “evangelical advisory board,” and were his staunch defenders after his 2020 defeat.

In the wake of Trump’s 2016 election, critics insisted that neither Paula White-Cain, nor the television audience she brought with her represented “mainstream evangelicalism.” Our research demonstrates that among those who identify as “born-again/evangelical,” however, charismatics and Pentecostals are growing rapidly, with political implications for future evangelical/born-again activism.

Pentecostals, largely born out of early 20th century revivals, formed denominations wherein supernatural experiences recorded in the Bible like speaking in tongues (ecstatic speech or speech-like sounds believed to be from God), divine healing, and prophecy were practiced by contemporary Christians.

While Pentecostalism grew, charismatics, a diverse collection of denominational and non-denominational Christians, also began emphasizing these practices in the mid to late twentieth century. For decades, such practices were discouraged or even banned by evangelical leaders, until the growth of charismatics forced them to reconsider.

In 2006, Pew Research Center reported that charismatics and Pentecostals, which Pew defined with an umbrella category of “Renewalist,” constituted around 23% of American Christians. By 2011, Pew found that Pentecostals and charismatics outnumbered evangelicals worldwide by about 2:1, making up 26.7% of Christians globally.

This rapid growth is shifting the nature of “born-again evangelicalism” in the United States. Our recent research indicates that a significant percentage of those who now identify as “born-again” are, in fact, worshiping in charismatic or Pentecostal spaces.

Understanding — and Measuring — Charismatic Christianity

A major challenge of identifying the size and scope of charismatic Christianity is that practitioners resist traditional institutional measures of American religiosity. Unlike other groups, which are commonly analyzed by church attendance, membership rolls, denominational affiliation or congregational size, charismatics worship in Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox churches, as well as non-denominational congregations.

In addition, the term “charismatic,” does not have the same brand recognition as “evangelical.” The term may not be recognized by some who worship in charismatic churches and others may identify with more traditional religious affiliations. A respondent who speaks in tongues, for example, may very well identify first as Roman Catholic or Baptist before choosing “charismatic” on a survey.

In April 2023, with support from the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI), we conducted an online, national survey through Qualtrics Panels of 1,100 adults living in the United States with an oversample of Latinx and AAPI individuals. While participants were volunteers (e.g. not a random sample), we employed gender, nativity, education, and age quotas to ensure that our Latinx, AAPI, and non-Latinx/AAPI sub-samples are representative of national patterns. The forthcoming analysis focuses on the 586 self-identified Christians (e.g. Catholic, Protestant, Mormon, Eastern/Greek Orthodox, and born-again/evangelical) in our sample who indicated that they attended religious services at least a few times a year.

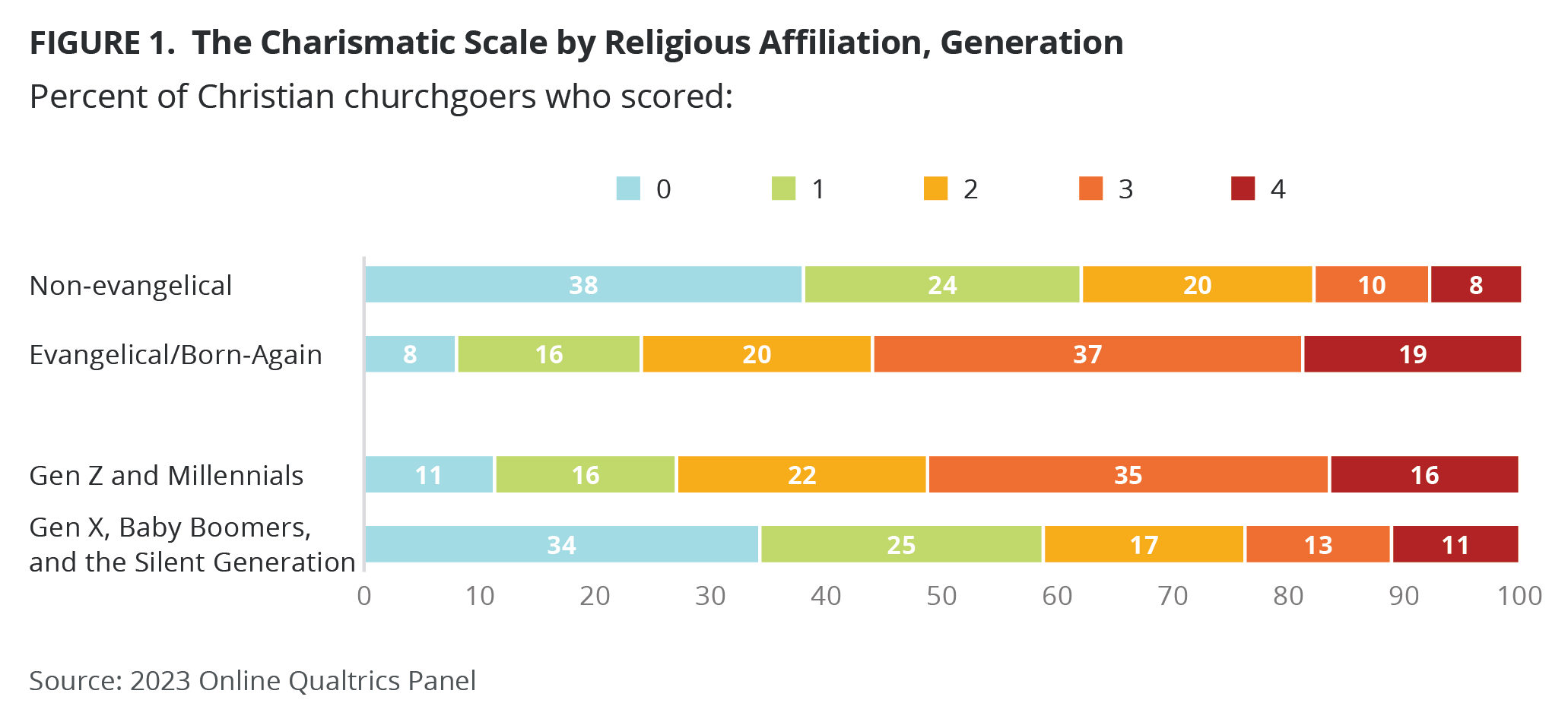

To identify charismatics, we asked respondents whether they attended religious services where people engage in signature practices and beliefs of Pentecostal and charismatic movements: speaking in tongues, receiving direct revelation from God, divine healing, or receiving a definite answer to a prayer. For our purposes, we describe those who have witnessed or experienced three or more of these practices at religious services as “charismatic”.

Notably, of those who identify as “born-again,” 56% experienced three or more of these practices and 19% all four. However, these percentages decline to 18% and 8% (respectively) among non-evangelical Christians. This suggests that many of those we call evangelical/born-again are worshiping in congregations that embrace charismatic or Pentecostal practices.

In recent years, prominent charismatic churches have targeted and succeeded in recruiting younger audiences. The successful and rapid expansion of Hillsong (before its recent scandals) demonstrated how these churches appeal to young, urban Christians. Indeed, we found that around half of Gen Z and millennial churchgoers report attending charismatic services, compared with only 24% of older respondents.

What this growing, young group of Pentecostals and charismatics means for politics

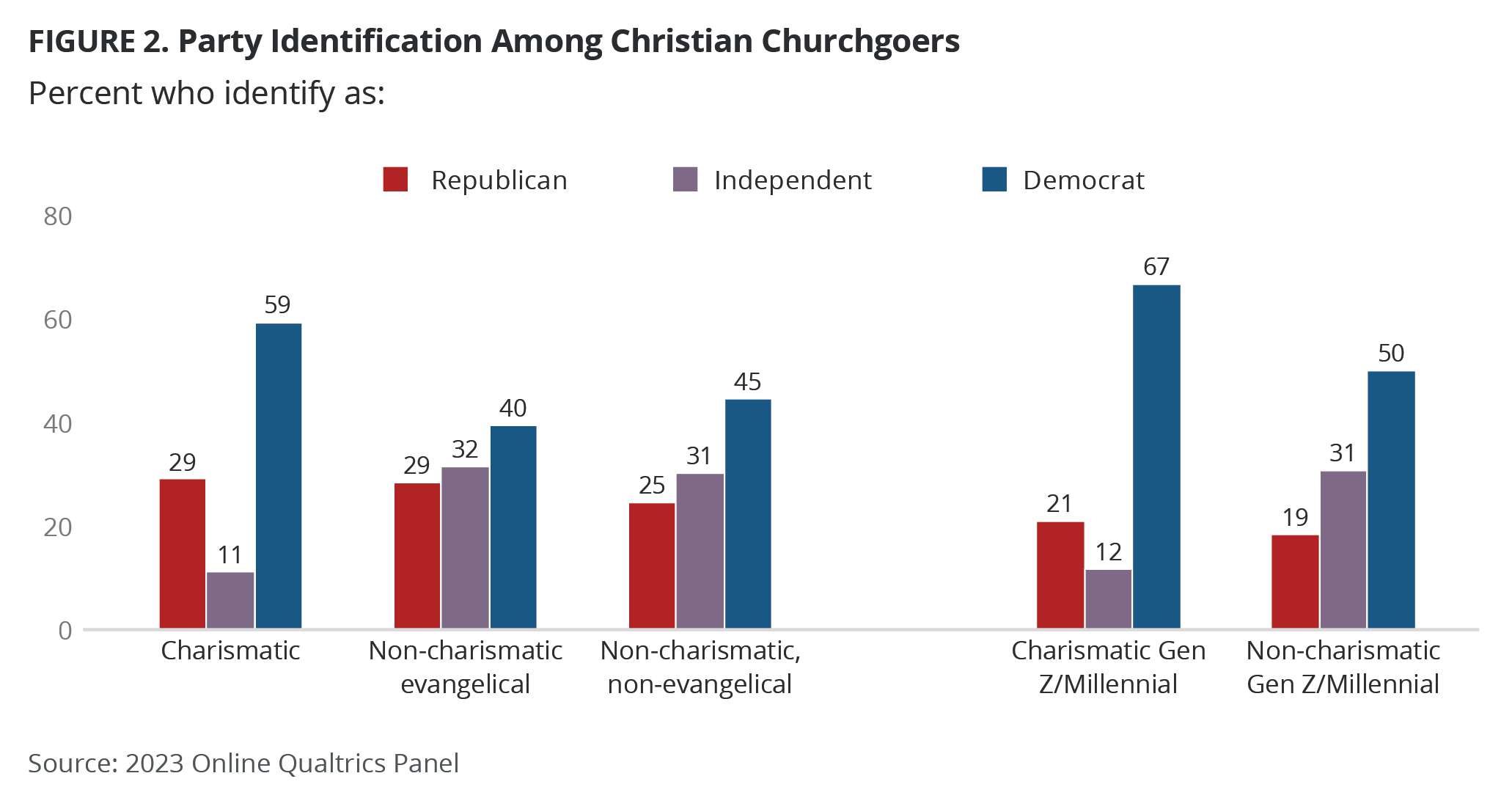

Because our survey oversampled Latinx and AAPI individuals, our sample is more heavily Democratic. Even among charismatics and non-charismatic evangelicals, we find higher than expected affiliation with the Democratic party (59% and 40% respectively). Unsurprisingly given generational trends, we also find that 67% of charismatic Gen Zers and millennials and 50% of their non-charismatic peers similarly identify with the Democratic party. What is surprising, though, is that despite these high rates of Democratic identifiers among charismatics compared to others, we still find charismatics consistently support conservative policies at higher rates than their non-charismatic peers who have lower rates of Democratic party affiliation.

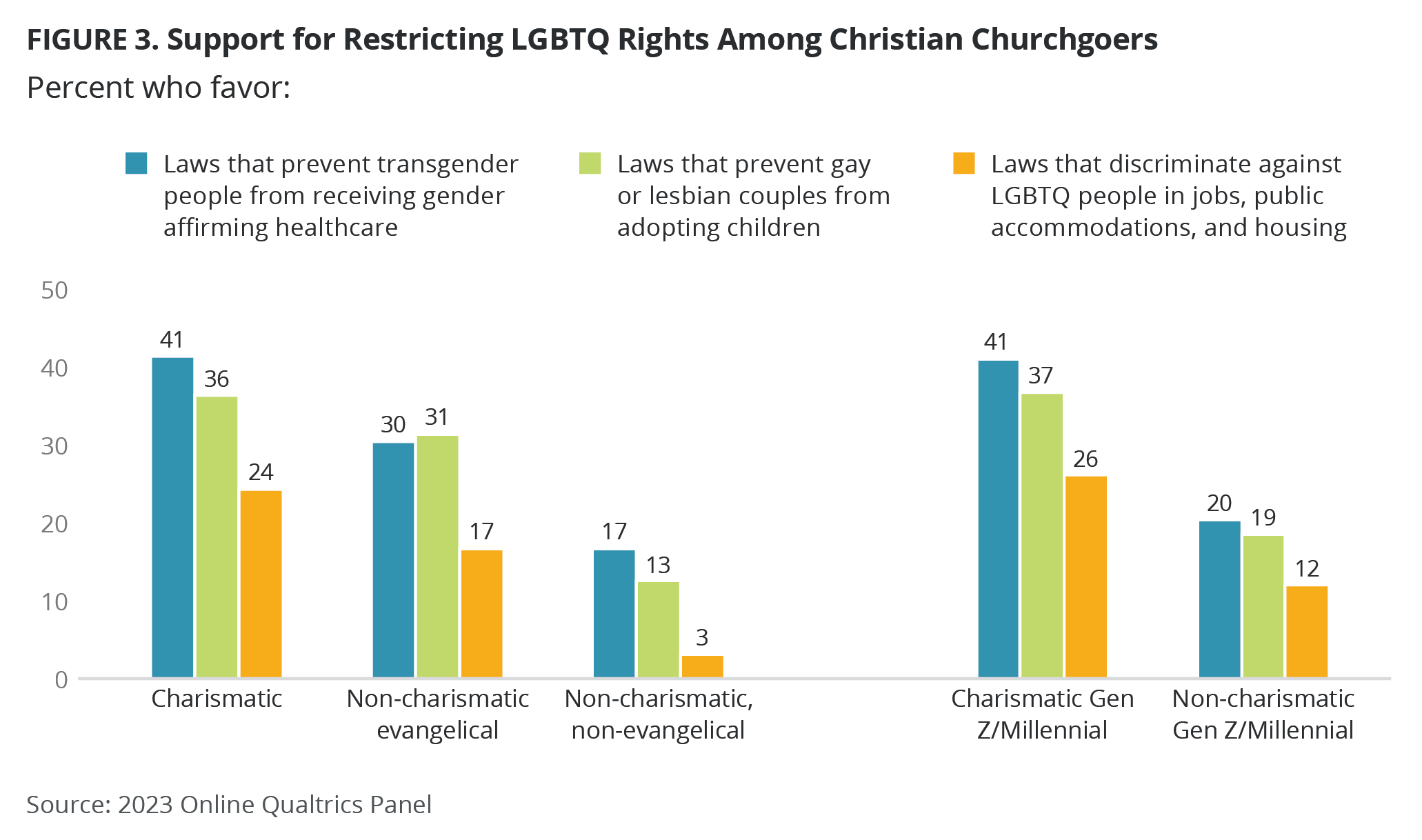

Charismatics are more supportive of restrictions on gender affirming care for transgender people (41%) compared to non-charismatic evangelicals (30%) and other Christians (17%). Gen Z and millennial charismatics are also more likely to support these restrictions compared to their non-charismatic peers, 41% to 20%. Support for laws which would prevent gay and lesbian couples from adopting children is 5% higher among charismatics compared to non-charismatic evangelicals and 23% higher compared to other Christians. Once again, Gen Z and millennial charismatics are 16% more supportive of such restrictions than non-charismatics in their generation.

Although only a minority of Americans support laws that would discriminate against LGBTQ people in jobs, public accommodations, and housing, charismatics are once again the most receptive. While only 3% of non-charismatic, non-evangelical Christians favor these policies, that number climbs to 17% for non-charismatic evangelical Christians and 24% for charismatics. Over a quarter of Gen Z and millennial charismatics support these discriminatory laws compared to 12% of non-charismatics in their age group.

Questions about other social issues underscore the differences between charismatics and other evangelicals. Post-Dobbs, the public is even less supportive of highly restrictive abortion policies. But among charismatics in our sample, 24% believe that abortion should never be permitted by law, compared to 12% of non-charismatic evangelicals, and 10% of other Christians. Although abortion bans remain unpopular among Gen Z and millennials, younger Christians who worship in charismatic spaces are more supportive (22%) compared to those who do not (13%).

While Gen Z and millennials often espouse more progressive attitudes towards the LGBTQ community, our research suggests that a growing subset of these Christians are moving in the opposite direction. Although church attendance in the United States has been declining for years, those Christians who do attend are worshiping in more charismatic spaces where younger does not mean less conservative, regardless of which party they affiliate with. On the contrary, while some evangelical denominations decline, and generational replacement is not assured, charismatic places of worship are better positioned than others to replenish the ranks of Christian conservatives in the years to come.