Crime Concern and the 2022 Midterms

Many observers predicted that the 2022 midterms would bring a “red wave” of success for Republican candidates. And yet, as we now know, the election turned out quite differently, with Democrats holding the Senate and losing far fewer House seats than many thought possible. The lack of an outright Republican midterm victory may indicate that the GOP needs a major strategy reboot if it is to succeed in future elections. Calls for change have been particularly loud in the aftermath of Republican Senate candidate Herschel Walker’s run-off defeat in Georgia in December.

One possible explanation for the midterm stumble might be that Republicans are frustrated with Donald Trump’s influence on the party, particularly after general election voters rejected a number of Trump-like candidates. Another possibility is that the issues emphasized by Republican candidates carried less cachet with voters than strategists believed they would. Many expected crime to be a major factor in the midterms, and many Republican candidates made blunt, Trump-style “law and order” anti-crime appeals a major part of their campaigns. In the boldest attempts to appeal to white voters’ fear of crime, some Republican ads mobilized imagery with strong racial overtones, echoing race-baiting “Willie Horton”-style campaigns of decades past.

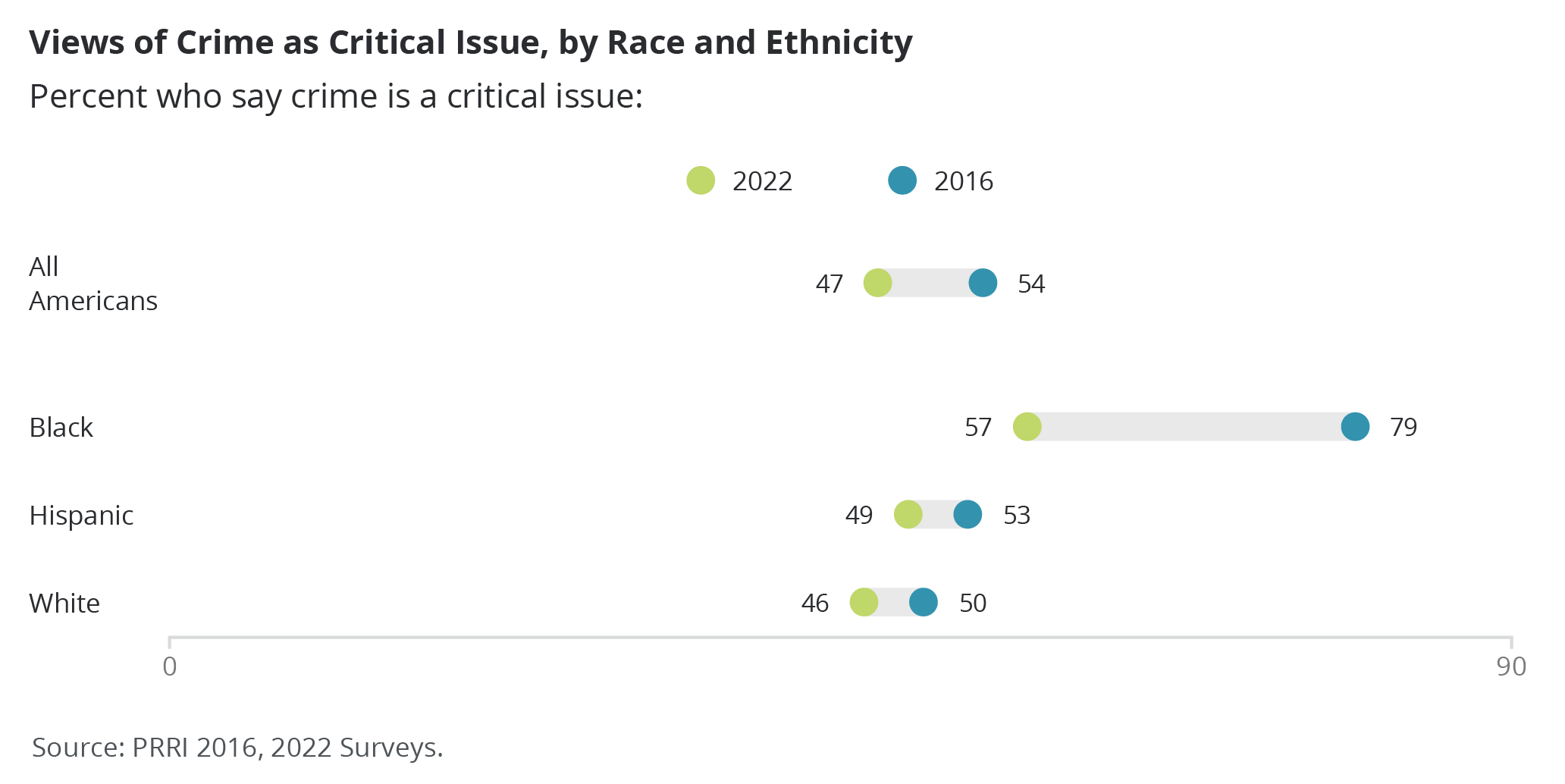

However, it seems that crime was not the grand motivating concern that many Republican politicians had hoped it would be, and it was even less influential in this election than it has been in the past. In exit polling, crime was far outpaced by inflation and abortion as the issues considered most important by voters. And in the same way that Trump-style conservatism may be on the outs with the general electorate, aggressive Republican appeals to the dangers of crime may be less effective than they were in years past. In the September 2022 American Values Survey, PRRI found that 47% of Americans saw crime as a critical issue, up slightly from a year earlier (43%). By contrast, in 2016 and 2017, when support for Trump was at its height, 54% saw crime as a critical issue.

National crime rates may provide a clue as to why law-and-order appeals weren’t more persuasive. Violent crime rates have remained relatively stable for the past few years. The murder rate did climb significantly during the pandemic, for reasons that are unclear, but murder, like violent crime more generally, has declined overall since the 1990s.

Despite these larger trends, crime remains a strong motivating concern for certain groups of American voters. In fact, it is a major area of concern among a group that the GOP has largely failed to court: Black voters. In PRRI’s American Values Survey, 57% of Black Americans reported that crime would be a critical issue for them in the November 2022 elections, while only 46% of whites and 49% of Hispanics said the same. This percentage is much lower than it was in 2016, when 79% of Black Americans said they saw crime as a critical issue, compared to 50% of whites and 53% of Hispanics, but the comparable difference between these groups is still notable.

This pronounced concern likely reflects the higher rates of crime and violence in predominantly Black neighborhoods — rates that are linked to historical legacies of racism, economic deprivation, and lack of public investment. At the same time, it is important to keep in mind that Black Americans also tend to be more skeptical of the American criminal justice system, owing to its long history of unfairness toward racial minorities and of over-policing , and targeting communities of color.

This raises the question of what future political candidates can do to address crime concerns in a way that helps them achieve electoral success. Republicans and Democrats alike might rethink playing to crime fears in the style of Trump, with blunt, racially coded law-and-order appeals, since this appears to no longer be a winning national strategy. Instead, candidates could consider how, when thinking about crime and justice, the concerns of minority communities most affected by crime might be placed at the forefront. And politicians might note that what these communities routinely ask for is less law-and-order politicking, less simplistic, punitive justice, and more long-term public investment to create opportunities that have too long been denied.