What it Means to be American: Attitudes towards Increasing Diversity in America Ten Years after 9/11

Executive Summary

Ten years after the September 11th terrorist attacks, Americans believe they are more safe but have less personal freedom and that the country is less respected in the world than it was prior to September 11, 2001. A small majority (53 percent) of Americans say that today the country is safer from terrorism than it was prior to the September 11th attacks. In contrast, nearly 8-in-10 say that Americans today have less personal freedom and nearly 7-in-10 say that America is less respected in the world today than before the terrorist attacks.

Ten years after the September 11th terrorist attacks, Americans believe they are more safe but have less personal freedom and that the country is less respected in the world than it was prior to September 11, 2001. A small majority (53 percent) of Americans say that today the country is safer from terrorism than it was prior to the September 11th attacks. In contrast, nearly 8-in-10 say that Americans today have less personal freedom and nearly 7-in-10 say that America is less respected in the world today than before the terrorist attacks.

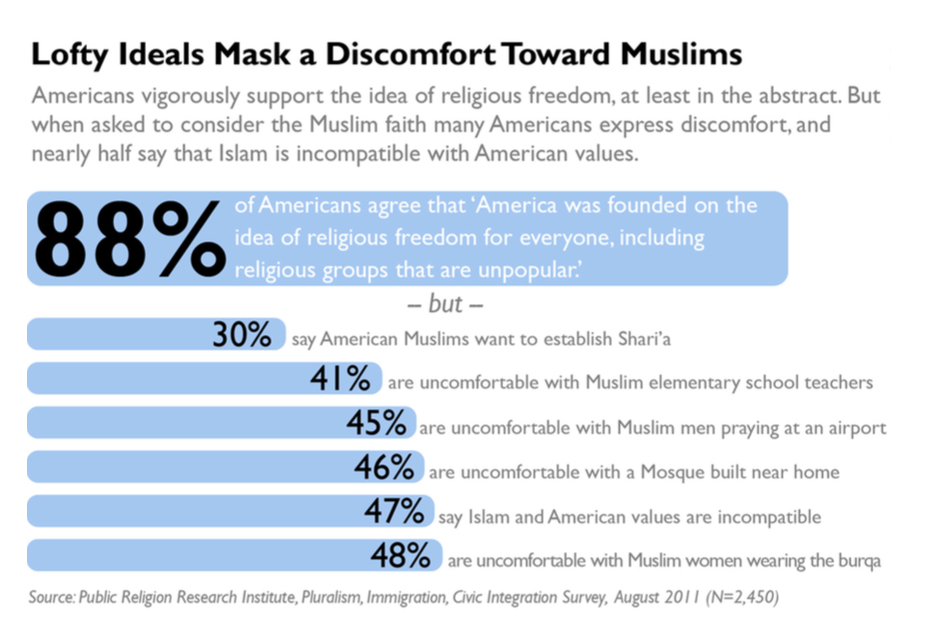

Americans strongly affirm the principles of religious freedom, religious tolerance, and separation of church and state. Nearly 9-in-10 (88 percent) Americans agree that America was founded on the idea of religious freedom for everyone, including religious groups that are unpopular. Ninety-five percent of Americans agree that all religious books should be treated with respect even if we don’t share the religious beliefs of those who use them. Nearly two-thirds (66 percent) of Americans agree that we must maintain a strict separation of church and state. Americans’ views of Muslims and Islam are mixed, however. As with other previously marginalized religious groups in U.S. history, Americans are grappling with the questions Islam poses to America’s founding principles and way of life.

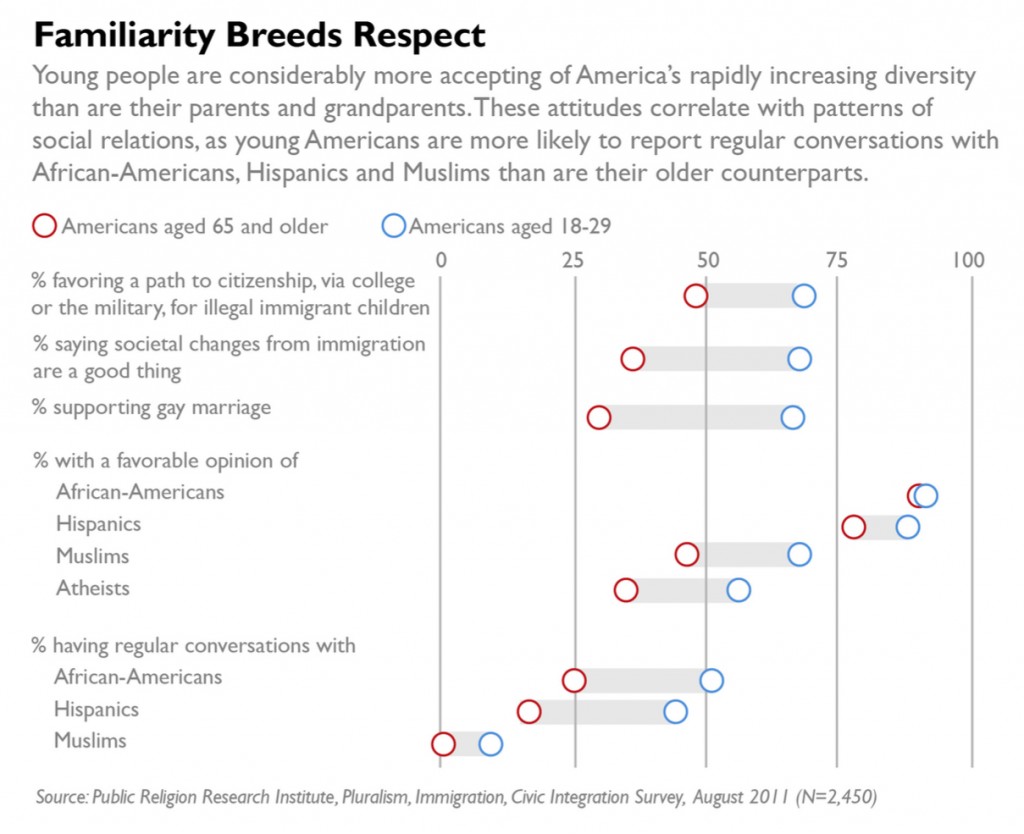

Americans who are part of the Millennial generation (ages 18-29) are twice as likely as seniors (ages 65 and older) to have daily interactions with African Americans (51 percent vs. 25 percent respectively) and Hispanics (44 percent vs. 17 percent respectively), and to speak at least occasionally to Muslims (34 percent vs. 16 percent respectively).

Nearly half (46 percent) of Americans agree that discrimination against whites has become as big a problem as discrimination against blacks and other minorities. A slim majority (51 percent) disagree.

- A slim majority of whites agree that discrimination against whites has become as big a problem as discrimination against minority groups, compared to only about 3-in-10 blacks and Hispanics who agree.

- Approximately 6-in-10 Republicans and those identifying with the Tea Party agree that discrimination against whites is as big a problem as discrimination against minority groups.

- Nearly 7-in-10 Americans who say they most trust Fox News say that discrimination against whites has become as big a problem as discrimination against blacks and other minorities. In stark contrast, less than 1-in-4 Americans who most trust public television for their news agree.

Americans are evenly divided over whether the values of Islam are at odds with American values and way of life (47 percent agree, 48 percent disagree).

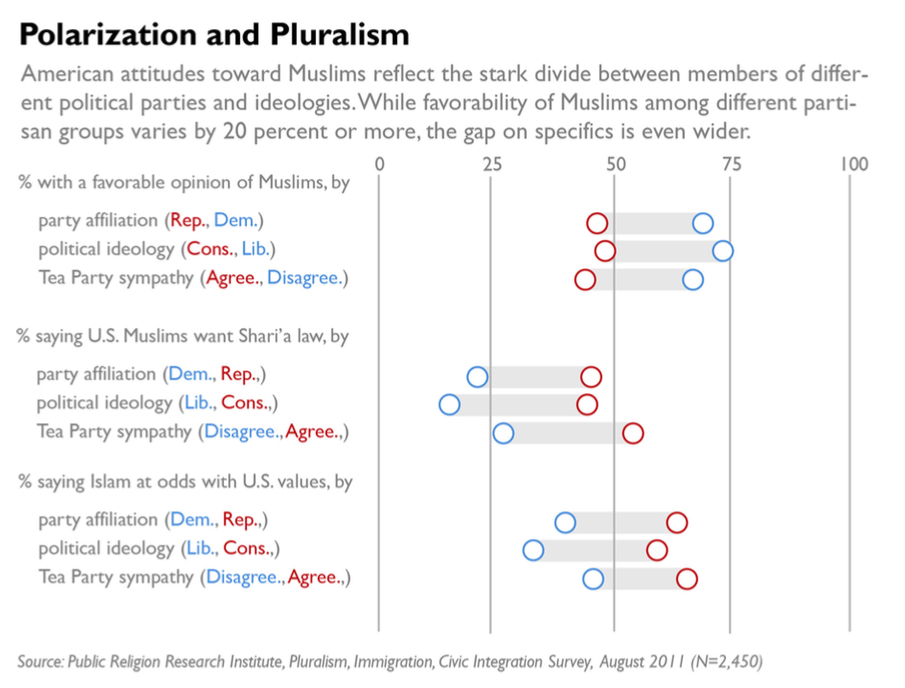

- Approximately two-thirds of Republicans, Americans who identify with the Tea Party movement, and Americans who most trust Fox News agree that the values of Islam are at odds with American values. A majority of Democrats, Independents, and those who most trust CNN or public television disagree.

- Major religious groups are divided on this question. Nearly 6-in-10 white evangelical Protestants believe the values of Islam are at odds with American values, but majorities of Catholics, non-Christian religiously unaffiliated Americans, and religiously unaffiliated Americans disagree.

By a margin of 2-to-1, the general public rejects the notion that American Muslims ultimately want to establish Shari’a law as the law of the land in the U.S. (61 percent disagree, 30 percent agree).

- Over the last 8 months agreement with this question has increased by 7 points, from 23 percent in February 2011 to 30 percent today.

- Nearly 6-in-10 Republicans who most trust Fox News believe that American Muslims are trying to establish Shari’a law in the U.S. The attitudes of Republicans who most trust other news sources look similar to the general population.

A majority (54 percent) of the general public agree that American Muslims are an important part of the religious community in the U.S., compared to 43 percent who disagree.

Nearly 8-in-10 (79 percent) Americans say people in Muslim countries have an unfavorable opinion of the U.S., including 46 percent who say Muslims have a very unfavorable opinion of the U.S. Among Americans who believe that people in Muslim countries have an unfavorable view of the U.S., three-quarters believe that such views are not justified.

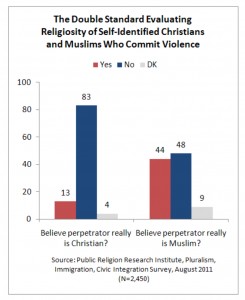

Americans employ a double standard when evaluating violence committed by self-identified Christians and Muslims. More than 8-in-10 (83 percent) Americans say that self-proclaimed Christians who commit acts of violence in the name of Christianity are not really Christians. In contrast, less than half (48 percent) of Americans say that self-proclaimed Muslims who commit acts of violence in the name of Islam are not really Muslims.

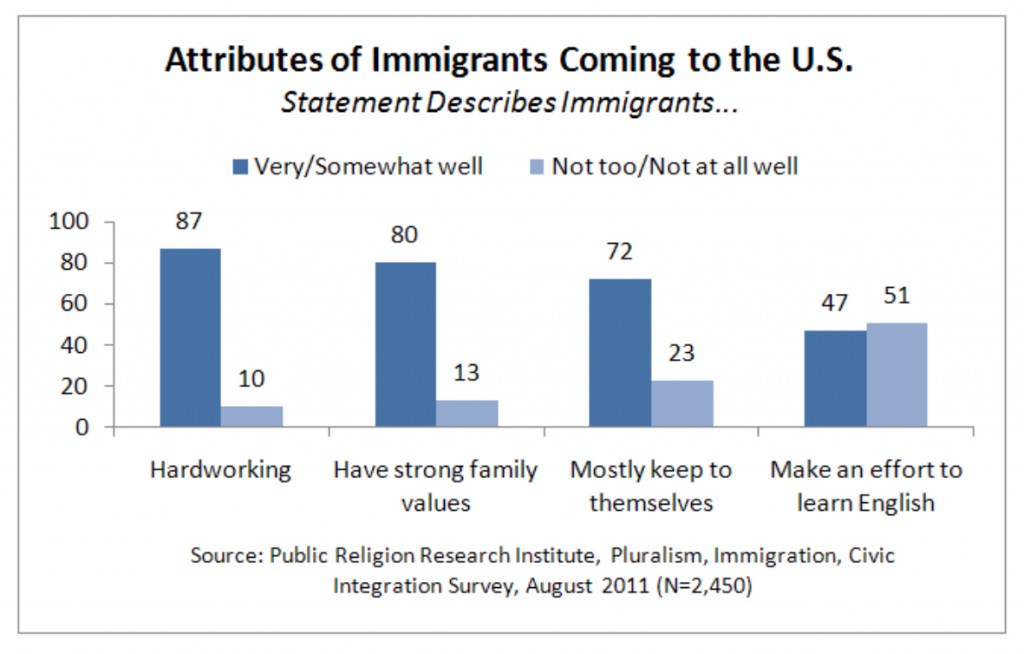

Americans hold a number of positive views about immigrants, but also have some reservations.

- Overwhelming majorities of Americans believe immigrants are hard working (87 percent) and have strong family values (80 percent), and a majority (53 percent) say newcomers from other countries strengthen American society.

- On the other hand, more than 7-in-10 (72 percent) also believe immigrants mostly keep to themselves, and a slim majority (51 percent) say they do not make an effort to learn English.

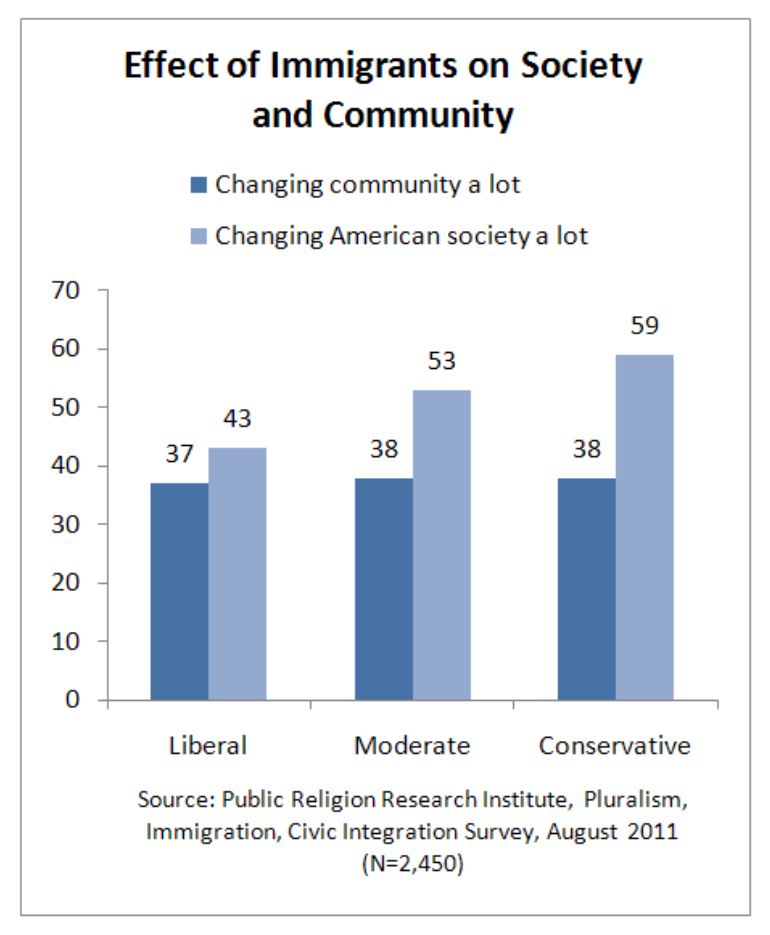

Americans are significantly more likely to say that immigrants are changing American society than their own community. A majority (53 percent) of Americans say that immigrants are changing American society and way of life a lot, compared to less than 4-in-10 (38 percent) who say immigrants are changing their community and way of life a lot. Conservatives are not more likely than liberals to say immigrants are changing their own communities a lot, but conservatives are significantly more likely than liberals to say that immigrants are changing American society a lot.

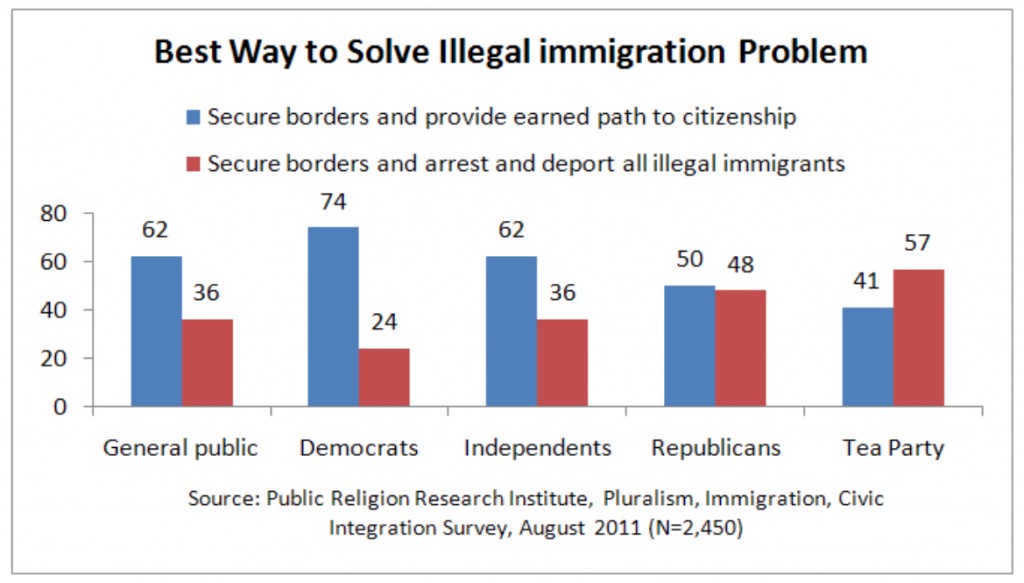

Americans’ views on immigration policy are complex, but when Americans are asked to choose between a comprehensive approach to immigration reform that couples enforcement with a path to citizenship on the one hand, and an enforcement and deportation only approach on the other, Americans prefer the comprehensive approach to immigration reform over the enforcement only approach by a large margin (62 percent vs. 36 percent).

- Nearly three-quarters of Democrats and more than 6-in-10 political independents say that both securing the border and providing an earned path to citizenship is the best way to solve the illegal immigration problem. Republicans are nearly evenly divided. In contrast, nearly 6-in-10 of Americans who identify with the Tea Party movement say that securing the border and deporting all illegal immigrants is the best way to solve the illegal immigration problem.

- Majorities of every religious group say that best way to solve the country’s illegal immigration problem is to both secure the borders and provide an earned path to citizenship.

Americans express strong support for the basic tenets of the DREAM Act: allowing illegal immigrants brought to the U.S. as children to gain legal resident status if they join the military or go to college (57 percent favor, 40 percent oppose). And opposition to the DREAM Act is less fierce than opposition to broader reform proposals, suggesting that partial reforms based on an earned path to citizenship are likely to have a better chance of passing than broader legislation.

The survey findings suggest that we are in the midst of a struggle over what growing religious, racial and ethnic diversity means for American politics and society, and that partisan and ideological polarization around these questions will make them difficult to resolve. Nonetheless, this is a battle that has been waged before, and one that is likely to reach the same conclusion: New groups will—through hard work, community and an embrace of our founding values—become “American” while at the same time changing the meaning of being American in ways that, historically, have enriched the nation.

I. American Identity & Values 10 Years After September 11th

Ten years after September 11th, Americans continue to grapple with issues of security, tolerance, religious freedom, and pluralism—matters that lie at the heart of what it means to be American. The youngest generation of Americans is the most ethnically and religiously diverse generation in the country’s history, and the growing diversity in this generation and in society as a whole is challenging Americans’ commitment to these core principles.

This report and the underlying major national public opinion survey behind it examine several critical subject areas that have been prominent in American public life over the last ten years. The introduction considers Americans’ perceptions of safety, freedom, and international reputation in the wake of the U.S. response to September 11th. The first section examines basic attitudes towards racial, ethnic, and religious minorities in the country, including changing views about discrimination and reverse discrimination. The next section takes up attitudes toward Islam and Muslim Americans and a range of related issues about the place of Muslim Americans in society and the different way in which Americans evaluate violence committed by self-identified Christians and Muslims. Finally, the last section investigates a much older central part of the American story: attitudes towards immigrants and immigration policy.

Safer, but Less Free and Less Respected

Ten years after the September 11th terrorist attacks, Americans believe they are more safe, but have less personal freedom and that the country is less respected in the world than it was prior to September 11, 2001. A majority (53 percent) of Americans say that today the country is safer from terrorism than it was prior to the September 11th attacks, compared to 35 percent who believe the U.S. is less safe. In contrast, nearly 8-in-10 (77 percent) say that Americans today have less personal freedom and nearly 7-in-10 (69 percent) say that America is less respected in the world today than before the terrorist attacks.

There are significant differences in how the public views the current security situation in the country. For instance, Millennials (age 18 to 29) (59 percent), men (58 percent) and college educated Americans (60 percent) are more likely than seniors (age 65+) (47 percent), women (49 percent) and those with a high school education or less (49 percent) to say that Americans today are safer from terrorism today than before 9/11. Majorities of both Democrats and Republicans say Americans today are safer (59 percent and 54 percent respectively).

There are significant partisan differences in how Americans perceive America’s global reputation. Democrats are nearly twice as likely as Republicans to say that the U.S. is more respected today than it was before the September 11th terrorist attacks (28 percent to 16 percent), although majorities of both groups say the U.S. is less respected today. Perceptions of America’s global reputation are also linked closely to views about President Obama. Among those who approve of Obama’s job as president, 28 percent say the U.S. today is more respected in the world, while only 13 percent of those who disapprove of Obama’s job as president say this.

II. Racial, Ethnic, & Religious Minorities in the U.S.

Strong Affirmation of Religious Freedom, Tolerance, Separation of Church and State

Americans strongly affirm the principles of religious freedom, religious tolerance, and separation of church and state. Nearly 9-in-10 (88 percent) Americans agree that America was founded on the idea of religious freedom for everyone, including religious groups that are unpopular. Ninety-five percent of Americans agree that all religious books should be treated with respect even if we don’t share the religious beliefs of those who use them. Nearly two-thirds (66 percent) of Americans agree that we must maintain a strict separation of church and state.

As a number of findings below demonstrate, however, Americans do not always apply these principles evenly or consistently.

Favorability of Religious, Racial and Ethnic Minorities in the U.S.

Most religious, racial and ethnic groups are viewed relatively favorably in the U.S. although most Americans do not hold strongly favorable views. More than 8-in-10 Americans say they have a favorable opinion of African-Americans (89 percent) and Hispanics (82 percent). More than 8-in-10 Americans also report holding favorable views of Catholics (83 percent) and Jews (84 percent), two groups once the object of widespread prejudice in the country. Mormons are viewed favorably by two-thirds (67 percent) of the public, and a majority of the public also reports holding a favorable view of American Muslims (58 percent). Atheists are viewed least positively of any religious or ethnic group with less than half (45 percent) of the public reporting a favorable view and nearly equal numbers (46 percent) reporting an unfavorable view.

There are few significant differences in attitudes about African Americans, Hispanics, Catholics, Jews, and Mormons among the major political, religious and demographic groups in the country. However, there is considerable diversity of opinion about Muslims and atheists.

Roughly two-thirds of Democrats (65 percent), Millennials (68 percent), religiously unaffiliated Americans (68 percent), and non-Christian religiously affiliated Americans (69 percent) report holding a favorable view of American Muslims. In contrast, less than half of Republicans (47 percent), Americans who identify with the tea party movement (44 percent), seniors (46 percent), and white evangelicals (44 percent) report holding favorable views. Despite these demographic differences on the question of favorability, a strong majority (60 percent) of Americans overall—including agreement across religious and political groups—agree that too many Americans think that all Muslims are terrorists.

A similar pattern is evident in views about atheists. A plurality of Democrats (49 percent) and independents (49 percent) and majorities of Millennials (56 percent), non-Christian religiously affiliated Americans (62 percent), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (68 percent) hold a favorable view of atheists. Conversely, less than 4-in-10 Republicans (38 percent), seniors (35 percent), white evangelicals (28 percent) and black Protestants (26 percent) hold positive views of atheists.

Diversity of Social Networks: Interactions with Racial, Ethnic, Political, and Religious Groups

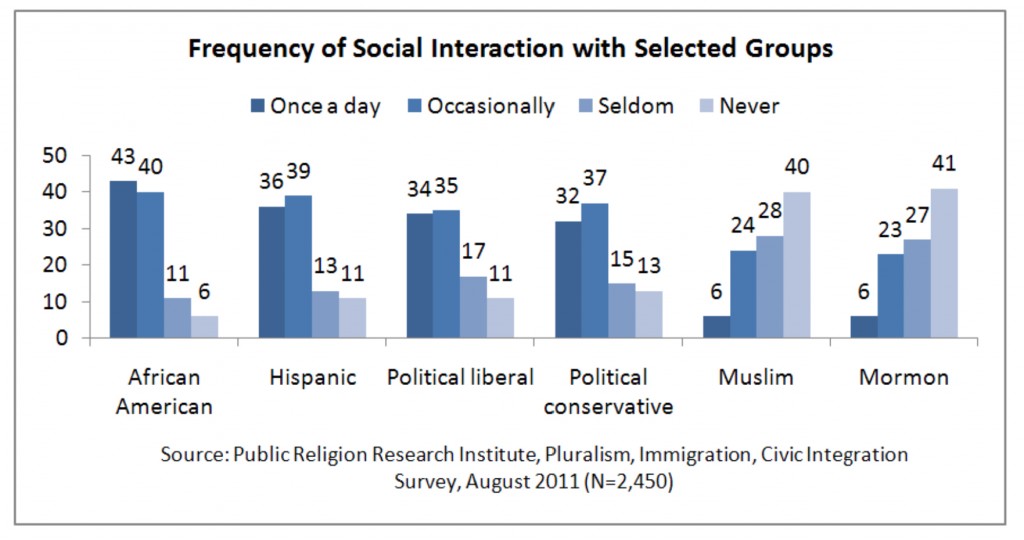

Americans report having more frequent social connections with ethnic minorities and people holding a range of political views than they have with religious minorities such as Muslims or Mormons. More than 8-in-10 Americans report having a conversation with an African-American person at least once a day (43 percent) or occasionally (40 percent). Three-quarters of Americans report having a conversation with someone who is Hispanic at least once a day (36 percent) or occasionally (39 percent). Roughly 7-in-10 Americans say they have conversations with political liberals or political conservatives at least occasionally. In contrast, only about 3-in-10 Americans say they speak with Muslims or Mormons at least occasionally (30 percent and 29 percent respectively).

There are significant differences in the patterns of social interaction between Millennials and seniors. Millennials are twice as likely as seniors to speak daily with African-Americans (51 percent vs. 25 percent respectively) and Hispanics (44 percent vs. 17 percent respectively). Millennials also report having daily conversations more frequently than seniors with both political liberals (40 percent vs. 22 percent respectively) and political conservatives (36 percent vs. 20 percent respectively). More than one-third (34 percent) of Millennials report speaking at least occasionally with someone who is Muslim, more than twice the number of seniors (16 percent) who say they at least occasionally talk with someone who is Muslim. The generation gap in social interaction is smallest among Mormons, with less than 3-in-10 of both seniors and Millennials reporting that they at least occasionally have conservations with someone who is Mormon.

Knowledge about Mormons, Views of Mormons as Christian Religion

Most Americans report that they do not know a lot about the religious beliefs and practices of Mormons. Seventeen percent of Americans say they know a lot, 55 percent say they know a little, and 27 percent say they do not know anything about religious beliefs and practices of Mormons.

Although relatively few Americans say they know a lot about the religious beliefs and practices of Mormons, more than 4-in-10 (41 percent) say they do not consider it a Christian religion. There is significant disagreement between different religious groups. For instance, nearly 6-in-10 (57 percent) white evangelicals say that the Mormon faith is not a Christian religion, as do a plurality (43 percent) of black Protestants. Majorities or pluralities of all other major religious groups and religiously unaffiliated Americans say that they consider the Mormon faith to be a Christian religion. Americans who say they know a lot or a little about the religious beliefs and practices of Mormons are much more likely than those who say they do not know anything to say they consider the Mormon faith a Christian religion.

Discrimination and Reverse Discrimination in Society

The Importance of Discrimination against Minorities and Reverse Discrimination

One-in-four Americans say that discrimination against minority groups is a critical issue facing the country today. Roughly 4-in-10 (41 percent) say it is one among many important issues, and less than one-third (31 percent) say it is not that important compared to other issues. Roughly 1-in-5 (18 percent) Americans believe that reverse discrimination—discrimination against whites—is a critical issue in the country today. Three-in-ten (30 percent) say it is one among many important issues, but nearly half (49 percent) say it is not important compared to other issues.

There are significant divisions by race on views about the importance of discrimination. African-Americans (53 percent) are three times as likely, and Hispanics (42 percent) are more than twice as likely, as whites (17 percent) to say that discrimination against minority groups is a critical issue. Whites are equally likely to say that discrimination (17 percent) and reverse discrimination (17 percent) are critical issues.

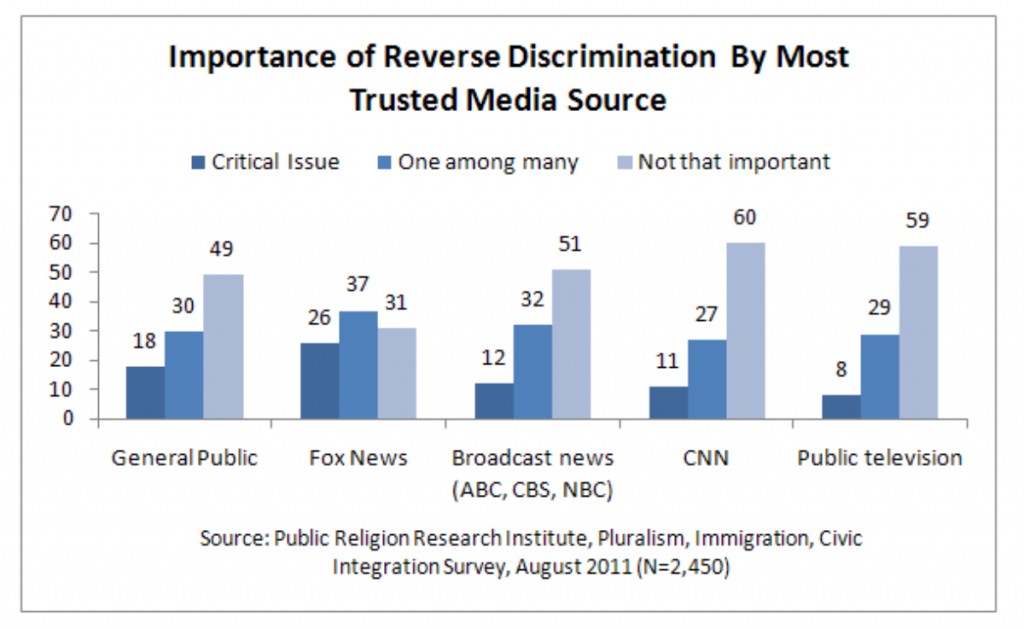

Views about the importance of reverse discrimination are strongly linked to television media consumption and trust. (1) Among Americans who say they most trust Fox News, 26 percent say reverse discrimination is a critical issue, nearly twice as many as say discrimination against minority groups is a critical issue (14 percent). At the other end of the spectrum, only 8 percent of Americans who most trust public television say reverse discrimination is a critical issue, compared to 27 percent who say discrimination against minorities is a critical issue.

Reverse Discrimination Compared to Discrimination against Minorities

Nearly half (46 percent) of Americans agree that discrimination against whites has become as big a problem as discrimination against blacks and other minorities. A slim majority (51 percent) percent disagree. There are substantial divisions in views about how large a problem discrimination against whites has become by race, political affiliation and age and most trusted media source.

Among whites, a slim majority (51 percent) agree that discrimination against whites has become as big a problem as discrimination against minority groups. Only about 3-in-10 blacks and Hispanics agree (29 percent and 30 percent respectively). Less than 4-in-10 (36 percent) Democrats agree that discrimination against whites has become as big a problem as discrimination against blacks and other minorities. More than 6-in-10 Democrats (62 percent) disagree. Approximately 6-in-10 Republicans (60 percent) and those identifying with the tea party (63 percent) agree that discrimination against whites is as big a problem as discrimination against minority groups. Political independents closely mirror the general public.

The largest differences in views about discrimination against minority groups and discrimination among whites is found between Americans who most trust Fox News and Americans who most trust public television. Nearly 7-in-10 Americans who say they most trust Fox News say that discrimination against whites has become as big a problem as discrimination against blacks and other minorities. In stark contrast, less than 1-in-4 (23 percent) Americans who most trust public television for their news agree, and three-quarters disagree.

III. Islam & Muslims in American Society

Knowledge about Muslims

Just as few Americans say they have frequent social interactions with Muslims, few also report having much knowledge about the religious beliefs and practices of Muslims. Fourteen percent say they know a lot about the religious beliefs and practices of Muslims, 57 percent say they know a little, and nearly 3-in-10 (29 percent) say they know nothing at all.

Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say they know a lot about Muslims (17 percent vs. 12 percent respectively). Americans who identify with the tea party movement are more likely to say they know a lot about Muslims than any other political group (21 percent). College graduates are twice as likely as Americans with a high school education or less to say they know a lot about Muslims (19 percent vs. 9 percent). Catholics are less likely to say they know a lot about the religious beliefs and practices of Muslims (7 percent) than any other religious group, including white evangelicals (16 percent), black Protestants (16 percent) the unaffiliated (15 percent) and white mainline Protestants (13 percent).

Americans who say they most trust Fox News and public television are more likely to report knowing a lot about the beliefs and practices of Muslims than Americans who trust other networks (20 percent and 19 percent respectively), although majorities of both say they only know a little (59 percent and 63 percent respectively). Americans who trust broadcast news networks are least likely to report knowing a lot about Muslims (7 percent).

The Compatibility of Islamic and American Values

Americans are evenly divided over whether the values of Islam are at odds with American values and way of life. Forty-seven percent of Americans agree that Islam is at odds with American values, and 48 percent disagree. There are large differences of opinion by political and religious affiliation, age, and trusted media source.

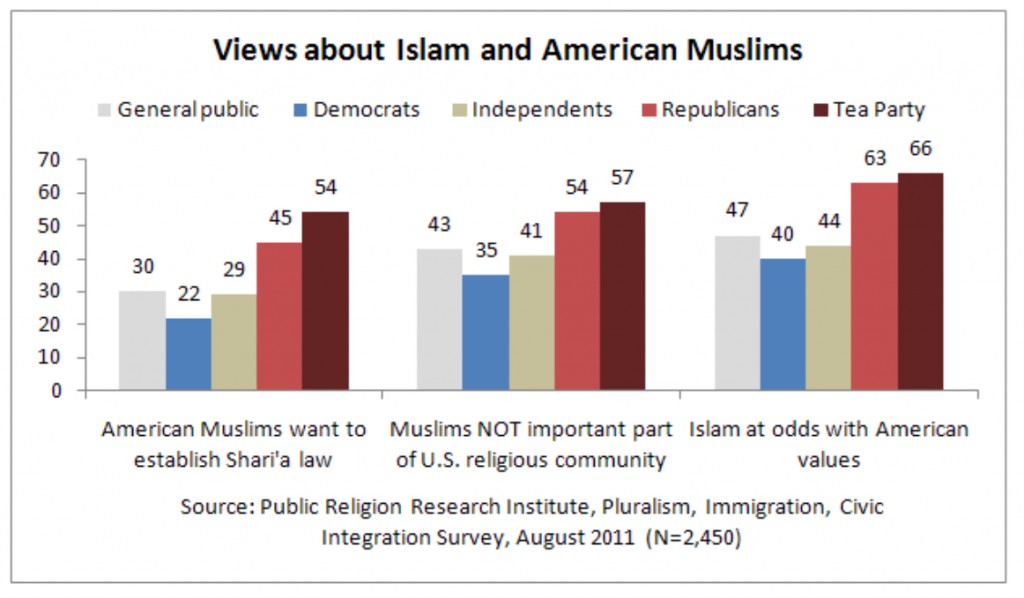

The political differences on views about Islam are striking. Nearly two-thirds (63 percent) of Republicans and Americans who identify with the Tea Party movement (66 percent) agree that the values of Islam are at odds with American values. In contrast, a majority of Democrats (55 percent) and political independents (53 percent) disagree.

Nearly 6-in-10 (59 percent) white evangelicals and a slim majority (51 percent) of black Protestants believe that Islam is at odds with American values. White mainline Protestants are evenly divided (47 percent agree and 48 percent disagree). A majority of Catholics (55 percent), religiously unaffiliated Americans (54 percent), and non-Christian religiously affiliated Americans (54 percent) disagree that the values of Islam are at odds with American values and way of life.

Younger and older Americans are also at odds. A majority of seniors (52 percent) agree that Islam is at odds with American values, while a majority (54 percent) of Millennials disagree that the values of Islam are at odds with American values.

Trust in Fox News is highly correlated with negative attitudes about Islam. More than two-thirds (68 percent) of Americans who most trust Fox News for their information about politics and current events say that the values of Islam are at odds with American values. In contrast, less than half of Americans who most trust broadcast network news (45 percent), CNN (37 percent), or public television (37 percent) agree that Islam is at odds with American values.

Views about Muslims and Shari’a Law

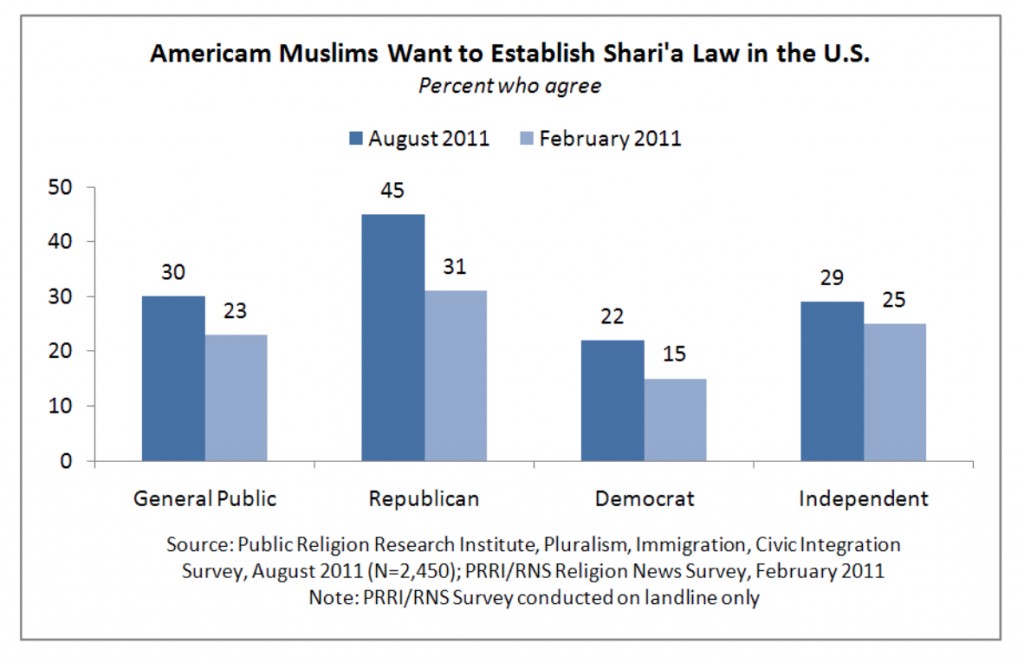

By a margin of 2-to-1, the general public rejects the notion that American Muslims ultimately want to establish Shari’a law as the law of the land in the U.S. (61 percent disagree, 30 percent agree). Similar alignments among demographic groups to those above are evident on this question.

Only 22 percent of Democrats and 29 percent of political independents believe that American Muslims are trying to establish Shari’a law in the U.S., compared to 45 percent of Republicans and a majority (54 percent) of Americans who identify with the tea party movement.

Solid majorities of every major religious group disagree that American Muslims ultimately want to establish Shari’a law in the U.S. White evangelical Protestants stand apart from other groups, with 46 percent agreeing that American Muslims ultimately want to establish Shari’a law in the U.S., and nearly equal numbers disagreeing (48 percent).

Millennials are much less likely than seniors to agree that American Muslims are trying to establish Shari’a law (23 percent to 37 percent respectively). Majorities of both groups disagree.

On this question Americans who most trust Fox News again stand out. A majority (52 percent) of Americans who most trust Fox News believe that American Muslims are attempting to establish Islamic law as law of the land. Less than one-third of Americans who most trust broadcast news networks (28 percent), CNN (20 percent) and public television (23 percent) agree with this statement.

Over the last 8 months views on this question have shifted significantly, with more Americans now reporting that they believe American Muslims want to establish Shari’a law in the U.S. (2) In February 2011, less than one-quarter (23 percent) of the public agreed that American Muslims were intent on establishing Shari’a law in the U.S. Three-in-ten Americans currently agree with this statement.

The increase in belief that American Muslims want to establish Shari’a law in America is much more pronounced among Republicans. Among Democrats, there is a 7-point increase in agreement (15 percent to 22 percent) over this period. Among political independents, the increase is just 4-points (25 percent to 29 percent). Among Republicans, however, there is a 14-point increase in agreement that American Muslims want to establish Shari’a law in the U.S.

Muslims as Important Part of American Religious Community

A majority (54 percent) of the general public agree that American Muslims are an important part of the religious community in the U.S., compared to 43 percent who disagree. Similar partisan, religious, and generational divides are also evident on this question.

Nearly two-thirds (63 percent) of Democrats and a majority (55 percent) of political independents agree that American Muslims are an important part of America’s religious community. Less than half of Republicans (44 percent) and members of the tea party movement (41 percent) agree. Majorities of both groups disagree (54 percent and 57 percent respectively). Majorities of all major religious groups agree that American Muslims are an important part of the religious community in the U.S., with the exception of white evangelical Protestants, among whom a majority (55 percent) disagree.

The Fox News Effect on Attitudes about Islam and American Muslims

There is a strong correlation between trusting Fox News and negative views of Islam and Muslims. This pattern is evident even among conservative political and religious groups.

Among all Republicans, nearly two-thirds (63 percent) say that Islam is at odds with American values. Among Republicans who most trust Fox News, more than 7-in-10 (72 percent) believe that Islam is at odds with American values. Among Republicans who most trust other news sources, less than half (49 percent) say Islam is at odds with American values, making their attitudes roughly similar to the general population.

A similar effect can be seen in beliefs about American Muslims and the establishment of Shari’a law. Nearly 6-in-10 (58 percent) Republicans who most trust Fox News believe that American Muslims are trying to establish Shari’a law in the U.S. Again, the attitudes of Republicans who most trust other news sources look similar to the general population (33 percent and 30 percent respectively).

Comfort Level with Muslims in Society

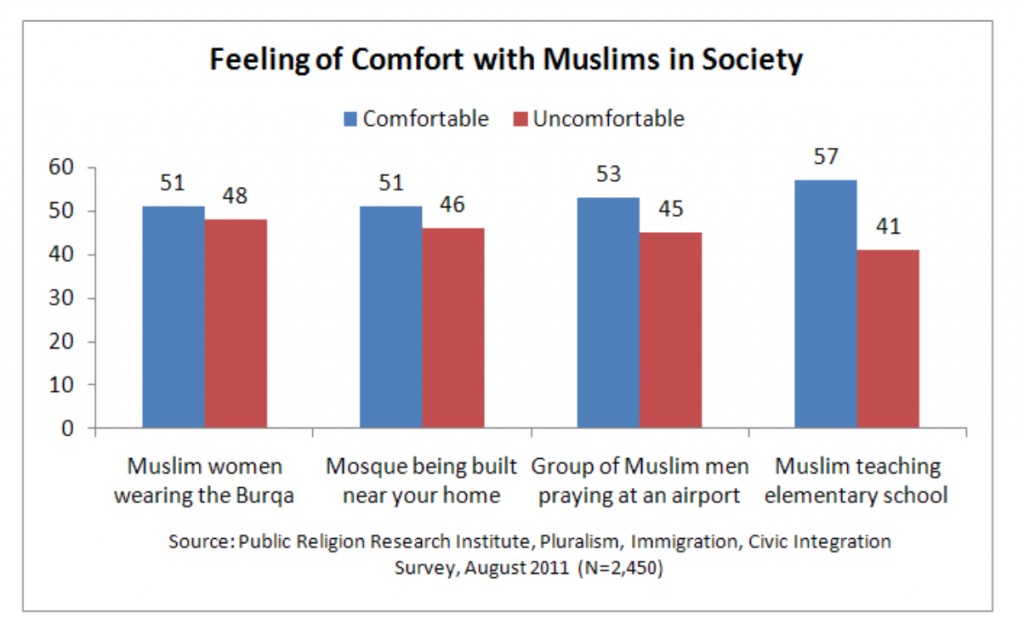

Americans are closely divided over how comfortable they feel with certain aspects of Muslim culture and Muslim religious expression in society. While small majorities say they would be comfortable with all public expressions of Muslim culture and religious expression included in the survey, more than 4-in-10 also say they would be uncomfortable with each one.

There are stark double-digit partisan divisions, however, between Republicans on the one hand, and Democrats and independents on the other. Nearly two-thirds (66 percent) of Democrats and 59 percent of independents report that they would be very or somewhat comfortable with a Muslim teaching at an elementary school in their community. Among Republicans, less than half (44 percent) say they would be comfortable with this. Majorities of Democrats (57 percent) and independents (55 percent) say they would be comfortable with a mosque being built near their home, compared to only 37 percent of Republicans and one-third of Americans who identify with the tea party movement. Similarly, majorities of Democrats (58 percent) and independents (55 percent) report that they would be comfortable with a group of Muslim men kneeling to pray in an airport. Again, less than half (45 percent) of Republicans and 4-in-10 tea party members say they would be comfortable with this. Equal numbers of Democrats and independents (54 percent) say that they would be comfortable with Muslim women wearing clothing that covers their whole body, including their faces. Roughly 4-in-10 (42 percent) Republicans would be comfortable with this.

There are major differences between religious groups in the level of comfort they report feeling with public expressions of Muslim identity and religious practice. For instance, a majority of white mainline Protestants (52 percent) and Catholics (51 percent) and nearly two-thirds of the religiously unaffiliated say they would be comfortable with a mosque being built near their home. Black Protestants are nearly evenly divided, with 47 percent saying they would be comfortable with a mosque being built near their home and half (50 percent) saying they would be uncomfortable. In contrast, only 35 percent of white evangelical Protestants say they would be comfortable with a mosque being build near their home; more than 6-in-10 (62 percent) say this would make them uncomfortable.

There are striking differences in levels of comfort felt by Americans by generation. More than 6-in-10 Millennials report being very comfortable with every expressions of Muslim religion and culture asked about in the survey, while less than 4-in-10 seniors report being comfortable with every measure. Nearly three-quarters (73 percent) of Millennials say that they would be comfortable with a Muslim teaching elementary school their community, compared to only 36 percent of seniors. More than 6-in-10 (61 percent) Millennials say they would be comfortable with a mosque being built near their home, compared to only 37 percent of seniors. More than 6-in-10 (62 percent) Millennials also say the would feel comfortable with a group of Muslim men praying at an airport, something about which only 39 percent of seniors report feeling comfortable. Two-thirds of Millennials report feeling comfortable about Muslim women wearing clothing that covers their entire body. Only half as many seniors (34 percent) report feeling comfortable about this.

Perceptions of Non-American Muslim Attitudes about the U.S.

Less than 1-in-5 (16 percent) Americans believe that people in Muslim countries have a favorable view of the United States. Nearly 8-in-10 (79 percent) say people in Muslim countries have an unfavorable opinion, including 46 percent who say Muslims have a very unfavorable opinion of the U.S.

Among Americans who believe that people in Muslim countries have an unfavorable view of the U.S., three-quarters believe that such views are not justified. Less than 1-in-4 (24 percent) say unfavorable views are justified.

Religious Extremism and Double Standards in Evaluating Religious Violence

Most Americans believe that religion is on balance a positive force in society although there is also widespread agreement that strong religious beliefs lead to extreme political views.

Religion as a Generally Negative or Positive Force in Society

Only 40 percent of Americans say religion causes more problems in society than it solves, compared to 58 percent who disagree. Republicans (27 percent) are significantly less likely to agree with this statement than Democrats (45 percent) or independents (44 percent), who remain more closely divided on this question.

Not surprisingly, there are significant differences of opinion between religious and non-religious groups but also between different religious traditions. Nearly three-quarters (74 percent) of white evangelicals and roughly 6-in-10 Catholics (59 percent), black Protestants (59 percent), and white mainline Protestants (57 percent) disagree that religion causes more problems than it solves. A slim majority (51 percent) of non-Christian religiously affiliated Americans and 6-in-10 religiously unaffiliated Americans agree that religion causes more problems in society than it solves.

Nearly three-quarters (73 percent) of Americans say that people with strong religious beliefs are more likely to have extreme political views. One-in-five say that people with strong religious beliefs are less likely to have extreme political views. There are no significant differences between Republicans, Democrats and independents. More than 7-in-10 Americans of every religious group also agree, with the exception of non-Christian affiliated Americans, among whom 64 percent agree.

Double Standard in Evaluating Violence Committed by Self-Identified Christians and Muslims

Americans employ a double standard when evaluating violence committed by self-identified Christians and Muslims. Americans are much more willing to say that Muslims who commit violence in the name of Islam are really Muslims than they are to say that Christians who commit violence in the name of Christianity are really Christians.

Americans employ a double standard when evaluating violence committed by self-identified Christians and Muslims. Americans are much more willing to say that Muslims who commit violence in the name of Islam are really Muslims than they are to say that Christians who commit violence in the name of Christianity are really Christians.

More than 8-in-10 (83 percent) Americans say that self-proclaimed Christians who commit acts of violence in the name of Christianity are not really Christians, compared to only 13 percent who say that these perpetrators really are Christians. In contrast, less than half (48 percent) of Americans say that self-proclaimed Muslims who commit acts of violence in the name of Islam are not really Muslims, compared to 44 percent who say that these perpetrators really are Muslims.

There are no large differences between Republicans (10 percent), Democrats (17 percent) and independents (14 percent) in views of whether a self-identified Christian who commits acts of violence in the name of Christianity is really Christian. However, there are significant partisan differences in views about whether a self-identified Muslim who commits acts of violence in the name of Islam is really Muslim. A majority (55 percent) of Republicans say that such a person is Muslim, compared about 4-in-10 Democrats (40 percent) and independents (39 percent). Majorities of Democrats (51 percent) and independents (53 percent) disagree that a self-identified Muslim who commits acts of violence is really Muslim.

More than 8-in-10 Americans in all major Christian groups say that Christians who commit violence in the name of their religion are not really Christian, including 86 percent of Catholics, 85 percent of white evangelical Protestants, 82 percent of white mainline Protestants, and 81 percent of black Protestants. More than two-thirds (68 percent) of non-Christian religiously affiliated Americans say that a self-identified Christian who commits acts of violence in the name of Christianity is not actually Christian.

White evangelical Protestants stand out strongly from other major religious groups in evaluating the religiosity of a self-identified Muslim who commits violence. Only roughly 4-in-10 white mainline Protestants (41 percent), Catholics (39 percent), black Protestants (36 percent), and non-Christian religiously affiliated Americans (35 percent) say a self-proclaimed Muslims who commits acts of violence in the name of Islam is really Muslim. In contrast, nearly 6-in-10 (57 percent) white evangelical Protestants believe that self-identified Muslims who commit acts of violence in the name of Islam are really Muslim.

Millennials are more likely than any other group to say that self-identified Christians who commit acts of violence are still Christian. Nearly 1-in-4 (24 percent) Millennials believe this, compared to just 7 percent of seniors. Roughly 4-in-10 (41 percent) Millennials believe that self-identified Muslims who commit acts of violence are still Muslim, compared to 43 percent of seniors.

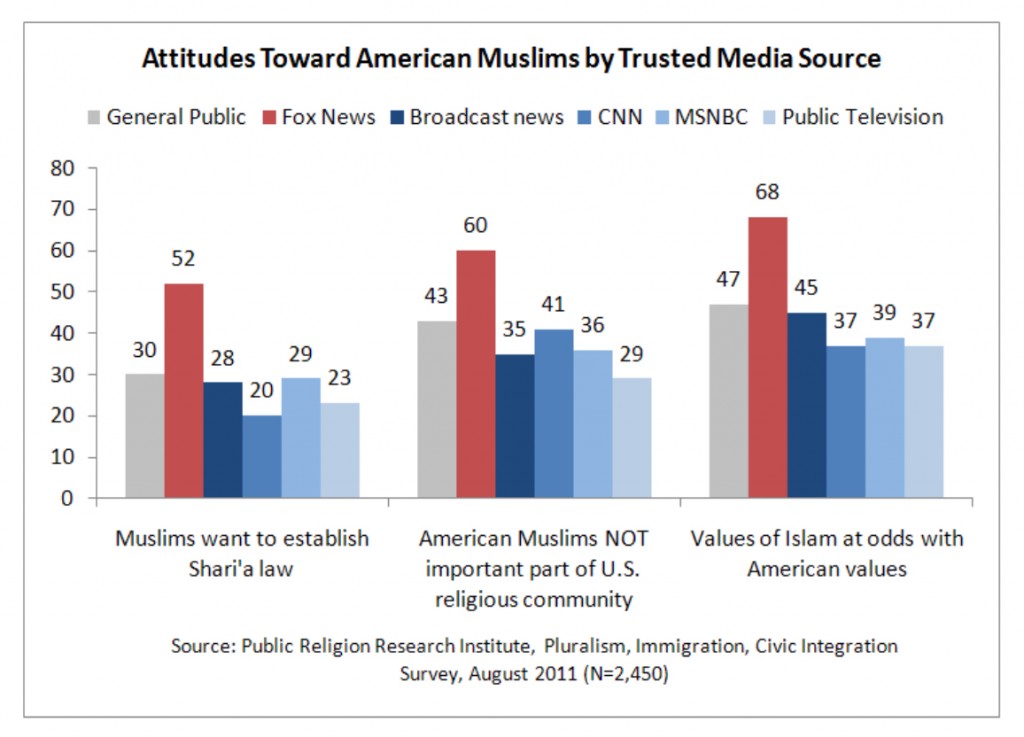

The Influence of Television News and Asymmetrical Polarization

Americans who most trust Fox News to provide news about politics and current events have much more negative attitudes about American Muslims and their motivations than Americans who trust other sources. Among the general public, only 3-in-10 (30 percent) believe that American Muslims ultimately want to establish Shari’a law or Islamic law as law of the land. Less than 3-in-10 Americans who most trust any other media sources besides Fox News agree with this statement, including those who most trust the broadcast news networks (28 percent), MSNBC (29 percent), public television (23 percent) and CNN (20 percent). Among Americans who most trust Fox News, however, a slim majority (52 percent) agree that Americans Muslims want to establish Shari’a law in the U.S.

A similarly large difference is evident on the question of whether American Muslims are an important part of the American religious community. Overall, only 43 percent of Americans disagree that Muslims are an important part of the American religious community, while a majority (54 percent) agree. Americans who most trust any other media sources besides Fox News are slightly less likely than the general public to disagree that American Muslims are an important part of the U.S. religious community, including Americans who most trust CNN (41 percent), MSNBC (36 percent), the broadcast news networks (35 percent) and public television (29 percent). Among Americans who most trust Fox News, however, fully 60 percent report that they disagree that American Muslims are an important part of the U.S. religious community.

Finally, this pattern is repeated on the question of whether the values of Islam are at odds with American values and way of life. The general public is nearly evenly divided on this question (47 percent agree, 48 percent disagree). Again, Americans who most trust other media sources besides Fox News are slightly less likely than the general public to agree that the values of Islam are at odds with American values. Among Americans who most trust Fox News, however, more than two-thirds (68 percent) say that the values of Islam are at odds with American values and way of life.

On each of these three questions, the gap between Americans who most trust Fox News and those who trust any other media sources is at least 19 points.

IV. Immigrants & Immigration

Views about Illegal Immigration and the Immigration System

More than 4-in-10 (43 percent) Americans report that illegal immigration is a critical issue facing the country, and an additional 35 percent say it is one among many important issues. Only 1-in-5 (21 percent) say it is not that important compared to other issues. Republicans are much more likely than Democrats to say that illegal immigration is a critical issue. A majority of Republicans (55 percent) and nearly two-thirds (63 percent) of Americans who identify with the tea party movement say that illegal immigration is a critical issue. In contrast, only about one-third (34 percent) of Democrats say that it is a critical issue, and nearly as many (29 percent) say that it is not that important compared to other issues. Political independents hold views that mirror the general public.

Only 4-in-10 Americans believe the current immigration system is generally working (5 percent) or working but with some major problems (35 percent). On the other hand, about 6-in-10 believe the immigration system is broken but working in some areas (38 percent) or is completely broken (19 percent).

Republicans (62 percent) and independents (61 percent) are significantly more likely than Democrats (49 percent) to say that the immigration system is broken but working in some areas or completely broken. Approximately two-thirds of Americans who identify with the tea party movement believe that the immigration system is broken but working in some areas (35 percent) or completely broken (31 percent).

Two-thirds of Americans say they know a lot (21 percent) or some (46 percent) about the immigration process in the country, compared to one-third who say they do not know much (21 percent) or know almost nothing (12 percent). Americans in the Midwest are least likely to be familiar with the immigration process in the country than Americans living in other parts of the country. Americans who most trust Fox News are more likely than those who trust any other news source to say they are knowledgeable about the immigration process. Nearly three-quarters say they know a lot (30 percent) or some (44 percent).

Views about Immigrants

There is widespread agreement among Americans about many attributes that describe immigrants coming to the U.S. today. Nearly 9-in-10 (87 percent) Americans believe the phrase “are hard working” describes immigrants well. Eight-in-ten Americans believe the phrase “have strong family values” describes immigrants well. On the other hand, more than 7-in-10 (72 percent) believe the phrase “keep to themselves” describes immigrants well, and a slim majority (51 percent) say the phrase “make an effort to learn English” does not describe immigrants well.

There are significant differences between Millennials and seniors and between Democrats and Republicans over whether immigrants today are trying to learn English, and perceptions on this attribute correlate with a number of other attitudes about immigrants and immigration policy. Nearly 6-in-10 (58 percent) Millennials believe that the statement, “they make an effort to learn English,” either describes immigrants very well or somewhat well, compared to less than 4-in-10 (37 percent) seniors. A majority (55 percent) of Democrats also believe this statement describes immigrants very or somewhat well, compared to only 34 percent of Republicans and 37 percent of Americans who identify with the tea party movement.

There are also significant religious differences on this question. A majority of the religiously unaffiliated and black Protestants believe that immigrants today are trying to learn English (56 percent and 52 percent) respectively. Majorities of white mainline Protestants (55 percent) and white evangelical Protestants (57 percent) disagree. Catholics and non-Christian affiliated Americans are about evenly divided.

Immigrants and Impact on Local Communities and American Society

A majority (53 percent) of Americans believe that the growing number of newcomers coming from other countries strengthens American society, compared to 42 percent who say that the growing number of newcomers from other countries threatens traditional American customs and values. There are significant differences of opinion between Americans of different political affiliations and generations.

A majority of Republicans (55 percent) and Americans who are part of the tea party movement (56 percent) say newcomers from other countries threaten traditional American customs and values. In contrast, majorities of Democrats (62 percent) and independents (56 percent) say newcomers strengthen American society.

A majority of Republicans (55 percent) and Americans who are part of the tea party movement (56 percent) say newcomers from other countries threaten traditional American customs and values. In contrast, majorities of Democrats (62 percent) and independents (56 percent) say newcomers strengthen American society.

Nearly two-thirds (64 percent) of Millennials say that the growing number of newcomers strengthens American society. Among seniors, a slim majority (51 percent) say the growing number of newcomers threatens traditional American customs and values.

Ironically, Americans are significantly more likely to say immigrants are changing American society and way of life than to say immigrants are changing their own community and way of life. A majority (53 percent) of Americans say that immigrants are changing American society and way of life a lot, roughly 4-in-10 (39 percent) say they are changing it a little, and only 8 percent say they are not changing American society at all. In contrast, less than 4-in-10 (38 percent) Americans say that immigrants are changing their community and way of life a lot, nearly half (47 percent) say they are changing it a little, and 14 percent say that immigrants are not changing their community at all.

There is evidence that the gap between views about how much immigrants are changing American society and how much they are changing local communities is at least partially driven by political ideology. Roughly equal numbers of self-identified liberals (37 percent), moderates (38 percent) and conservatives (38 percent) report that immigrants are changing their respective communities a lot. However, conservatives are much more likely than liberals to say that immigrants are changing American society a lot (59 percent vs. 43 percent respectively).

Among those who say that immigrants are changing American society a lot or a little, a majority (51 percent) say that this is a good thing, compared to 42 percent who say this is a bad thing. The pattern is nearly identical among those who say immigrants are changing their own communities a lot or a little. A majority (52 percent) of this group say that this is a good thing, compared to 41 percent who say this is a bad thing.

Among those who believe immigrants are changing American society, self-identified liberals are about twice as likely as self-identified conservatives to say that this is a good thing (72 percent to 36 percent). The ideology gap is nearly as large among those who say that immigrants are changing their community; nearly three-quarters (73 percent) of liberals say this is a good thing compared to less than 4-in-10 (39 percent) conservatives.

Immigration Policy: DREAM Act, Comprehensive Immigration Reform and Deportation

The DREAM Act

Americans demonstrate strong support for the basic tenets of the DREAM Act: allowing illegal immigrants brought to the U.S. as children to gain legal resident status if they join the military or go to college. Nearly 6-in-10 (57 percent) Americans favor this policy, compared to 4-in-10 who oppose it. Support for this policy is strongest among Millennials, among whom nearly 7-in-10 (69 percent) favor it; in contrast, only 48 percent of seniors favor this policy.

There is solid support among Democrats (70 percent) and political independents (56 percent) for allowing illegal immigrants brought to the U.S. as children to earn legal resident status if they attend college or join the military. In contrast, a majority (55 percent) of Republicans and nearly 6-in-10 (59 percent) Americans who identify with the tea party movement oppose the policy.

There is also solid support across all major religious groups, with the exception of white evangelical Protestants. Majorities of white mainline Protestants (54 percent), Catholics (58 percent), Black Protestants (64 percent) and the religiously unaffiliated (65 percent) favor allowing illegal immigrants brought to the U.S. as children to gain legal resident status if they join the military or go to college. White evangelical Protestants are the only religious group among whom a majority (52 percent) oppose this policy.

Comprehensive Immigration Reform and Deportation

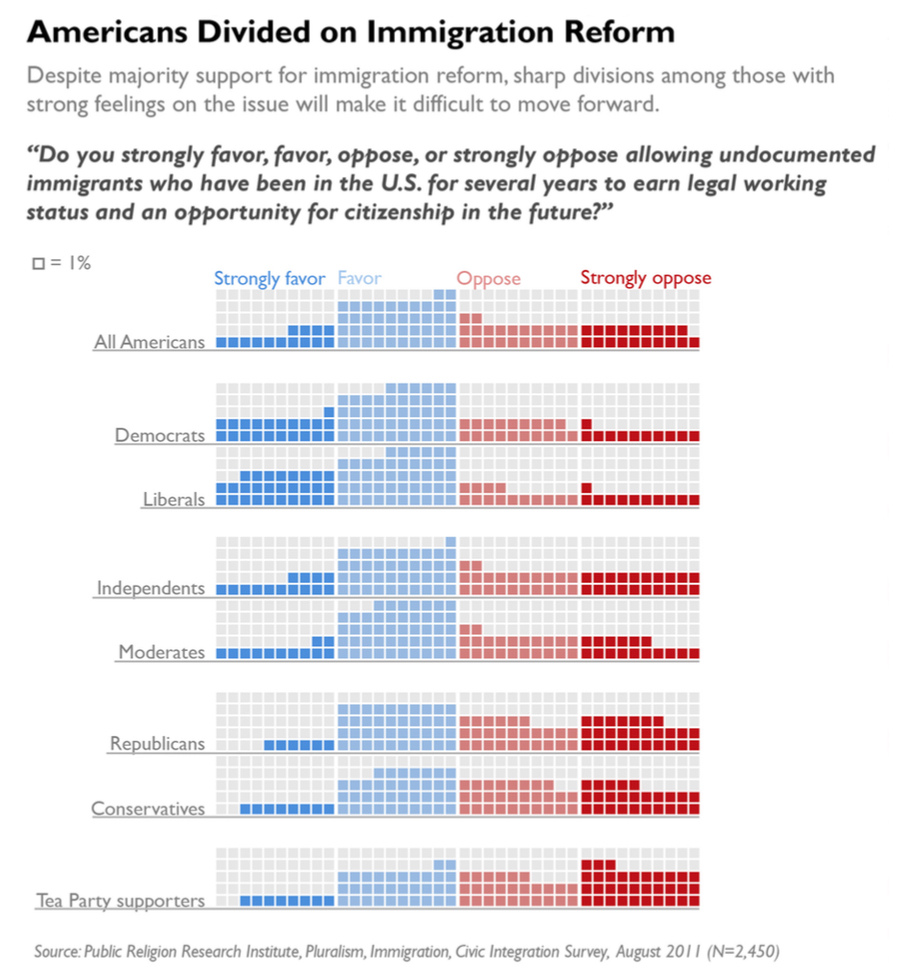

Americans’ views on the best approaches to immigration reform are complex. For example, a majority (56 percent) of Americans favor allowing undocumented immigrants who have been in the U.S. for several years to earn legal working status and an opportunity for citizenship in the future, compared to 41 percent who oppose such a policy.

On the other hand, a slim majority (51 percent) of Americans also agree that we should make a serious effort to deport all illegal immigrants back to their home countries, compared to nearly half (48 percent) who disagree. This support for deporting illegal immigrants has increased 9 points since early 2010. In March 2010, only about 4-in-10 (42 percent) Americans agreed that the U.S. should make a serious effort to deport all illegal immigrants back to their home countries, compared to a majority (56 percent) who disagreed. (3) Support for deportation increased evenly across the major political parties with both Republicans and Democrats register an 11-point increase in support for this approach over the last year.

However, when Americans are asked to choose between a comprehensive approach to immigration reform that couples enforcement with a path to citizenship on the one hand, and an enforcement and deportation only approach on the other, Americans prefer the comprehensive approach to immigration reform over the enforcement only approach by a large margin. More than 6-in-10 (62 percent) Americans say they prefer a strategy that secures the borders and provides an earned path to citizenship for illegal immigrants already in the country, compared to only 36 percent who support a strategy that secures the borders and seeks to arrest and deport all illegal immigrants already in the country.

There are major divisions in opinion by political affiliation. Nearly three-quarters (74 percent) of Democrats and more than 6-in-10 (62 percent) political independents say that both securing the border and providing an earned path to citizenship is the best way to solve the illegal immigration problem. Republicans are nearly evenly divided, with 48 percent saying deportation is the best solution and 50 percent saying providing an earned path to citizenship is the best solution. Americans who are part of the tea party movement stand out both from the general population and from Republicans on their approach to solving the illegal immigration problem. Nearly 6-in-10 (57 percent) of those who identify with the tea party movement say that securing the border and deporting all illegal immigrants is the best way to solve the illegal immigration problem.

There is broad support across the religious landscape for a comprehensive approach to immigration reform. Majorities of every religious group say the best way to solve the country’s illegal immigration problem is to both secure the borders and provide an earned path to citizenship, including 54 percent of white evangelicals, 57 percent of white mainline Protestants, 58 percent of black Protestants, 66 percent of the religiously unaffiliated, 68 percent of Catholics and 70 percent of non-Christian affiliated Americans.

V. A Nation United and Divided on Pluralism & Diversity

Americans are a tolerant people, but we are divided by tolerance itself. We are united in our support for religious freedom, but divided over what it means. A substantial majority would like to create a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants even as—at the very same time—a small majority would also deport all illegal immigrants.

The future points to an even more tolerant and open nation because young Americans are far more comfortable with and sympathetic to ethnic, racial and religious diversity than are older Americans. But this generational divide also translates into a political divide. If conservatives and Republicans disagree sharply with liberals and Democrats on matters of taxing and spending, they also differ substantially on a broad range of issues related to immigration and to the implications of racial, religious and ethnic diversity.

Ten years after September 11, 2001, we seem far less united as a nation. As a pioneer in the struggle for religious liberty and as a nation defined by immigration, we remain an exceptionally open country. Even Americans uneasy with diversity accept it in important ways as a norm. But we are so divided across partisan, ideological and generational lines that resolving the inevitable tensions that arise in a pluralistic society may prove to be less of a challenge than settling our political differences over what pluralism implies, and what it requires of us. Our national motto is “Out of many, one.” We find ourselves a very considerable distance from this aspiration—and politics, more than ethnicity, religion or race, is the reason why.

VI. Religious Liberty & American Muslims

Religious liberty stands at the heart of the American experiment. James Madison wrote in 1785 that “The religion . . . of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man; and it is the right of every man

to exercise it as these may dictate.” Just six years later the American people enshrined these sentiments in the First Amendment to the Constitution, which has shaped our understanding of religion and its role in our politics and society ever since.

This commitment to religious liberty remains strong today. Eighty-eight percent of Americans agree that “America was founded on the idea of religious freedom for everyone, including religious groups that are unpopular.” Ninety-five percent agree that “All religious books should be treated with respect even if we don’t share the religious beliefs of those who use them.”

Throughout American history, however, immigrants professing faiths outside the existing mainstream have tested the commitment to religious liberty. In the 19th century and much of the 20th, it was Catholics and Mormons who presented the most severe challenge. Mormons’ endorsement of polygamy was seen not only as an affront to Christian marriage but also as a threat to democracy. During the first national convention of the Republican Party in 1856, Mormon polygamy was denounced as one of the “twin relics of barbarism” (slavery was the other). Successive U.S. administrations, most of them Republican, hounded the Mormon church to the brink of legal extinction by the 1890s.

If anything, antipathy to Catholics went even deeper. Catholicism aroused two fears—that its theological principles were incompatible with liberal democracy and that it required trans-national loyalties to a “foreign potentate” (the Pope) that took precedence over American citizenship.

It took American Catholics a century to fully allay these fears, in part by tangibly demonstrating their loyalty to the United States, in part by reinterpreting Catholic teaching to eliminate the elements least compatible with liberal democracy—chief among them, the tendency toward theocracy and reservations about freedom of religion and conscience.

Americans’ current views of Muslims combine features of largely discarded attitudes toward Mormons and Catholics. Even though U.S. law virtually bars Muslim polygamy, other gender-related Islamic practices such as the wearing of the burqa make many Americans viscerally uncomfortable. Parallels with anti-Catholic attitudes of the past are even more striking. Nearly one third of respondents believe that American Muslims “ultimately want to establish shari’a” as the law of the land (much as a significant portion of American Protestants once feared that Catholics would enshrine their religion into American law if they had the opportunity). Nearly half think that Islamic values are incompatible with the American way of life—again, a view many Protestants once held toward Roman Catholicism. Highly publicized events such as the Fort Hood shootings appear to have stoked fears that Muslim loyalty to the trans-national umma trumps the claims of American citizenship. These fears may help explain why 46 percent of Americans express discomfort at the prospect of a mosque being built near their home, while 45 percent indicate discomfort with a group of Muslim men kneeling to pray at an airport.

This finding points to the brooding presence of 9/11 in the American consciousness. While leaders for the most part have endeavored to draw a sharp distinction between the struggle against “terror,” “violent extremism,” and “jihadism” on the one hand and Islam on the other, their efforts have been only partly successful. Forty-four percent of Americans believe that when people commit acts of violence in the name of Islam, they are acting as Muslims. To put that number in perspective, only 13 percent of Americans said that Christians who committed acts of violence in the name of Christianity were acting as Christians.

Given the provenance of the 9/11 plotters, such views are to some extent inevitable. The gap between these sentiments and government policy is notable, however, especially in comparison to previous episodes of conflict in American history. During World War I, German-Americans were subject to intense persecution, and many of their newspapers and cultural institutions were shut down. After Pearl Harbor, let us recall, more than 100,000 Japanese-Americans were herded from their homes and interned in concentration camps.

It is perhaps a reflection of cultural and legal changes in recent decades that even the shock of 9/11 did not occasion such extreme reactions. Respect for civil liberties is more entrenched than it once was, and the large flow of immigrants since the mid-1960s has accustomed younger Americans to a more diverse society. Muslims in America have benefitted from these trends. Despite highly publicized outbursts from some localities and candidates for political office, more than three in five Americans reject the contention that American Muslims want to establish shari’a as the law of the land. In addition, 54 percent of Americans regard Muslims as an important part of the U.S. religious community, and 60 percent feel that “Too many Americans think that all Muslims are terrorists.” In the tug of war between respect for religious diversity and the memory of 9/11, the forces of openness appear to have the upper hand, at least when we view the country as a whole. But the aggregate numbers conceal stark differences on these matters among parties, ideologies and demographic groups. These differences are the subject of the next section.

VII. Partisan Polarization & American Pluralism

Previous periods of rapid demographic change in the United States have sparked intense disagreements about the effects of growing religious and ethnic pluralism on American society. The surge of Catholic immigrants in the decades before the Civil War evoked intense nativist sentiments, crystallized in the Know Nothing movement and related third parties. Another surge in the decades before World War I led to fears that America’s political culture would be overwhelmed, focused attention on the need to “Americanize” tens of millions of newly arrived immigrants, and led to restrictive policies that endured from the mid-1920s until the mid-1960s. The flood of Latino immigrants, legal and illegal, that arrived after America’s gates swung back open has given rise to another decades-long conflict over immigration policy that has not yet ended.

Today’s disagreements about religious and ethnic pluralism are taking place in especially inhospitable circumstances. Partisan and ideological polarization now stands at levels not seen in more than a century. Not surprisingly, responses to Muslim Americans and to immigration generally often divide along lines of party identification and ideological conviction.

Consider the diverse responses evoked by the growth of Islamic immigrants and adherents. While 58 percent of Americans are very or mostly favorable toward Muslims, that figure drops to 47 percent of Republicans (versus 65 percent of Democrats) and only 44 percent of tea party identifiers (versus 61 percent of non-identifiers). The ideological breakdown tells a similar story: 73 percent of liberals and 63 percent of moderates but only 48 percent of conservatives have favorable attitudes toward Muslims.

The partisan and ideological gap on specifics is even starker. Forty-five percent of Republicans, 44 percent of conservatives, and 46 percent of white evangelicals (the bulk of whom identify themselves as conservative and Republican) believe that American Muslims are intent on establishing shari’a as the law of the land, versus 22 percent of Democrats and 15 percent of liberals. Tea party identifiers are twice as likely to harbor that belief (54 percent) as are non-identifiers (27 percent). Sixty-three percent of Republicans, 59 percent of conservatives and white evangelicals, and 66 percent of tea partyers believe that Islam is incompatible with America’s values and way of life, versus 40 percent of Democrats, 33 percent of liberals, and 45 percent of those who do not identify with the tea party. Questions about Muslims teaching at elementary schools, building mosques in neighborhoods, or kneeling to pray at airports, reveal similar ideological and partisan disparities. (The prospect of mosques in their neighborhoods makes 62 percent of white evangelicals somewhat or very uncomfortable.)

And although Americans overall agree that people in Muslim countries have an unfavorable opinion of the United States, there is a significant difference between those who think this disenchantment is justified and those who feel it is unjustified. Of all those who said Muslims overseas have an unfavorable opinion of the U.S., only 15 percent of conservatives, 14 percent of Republicans, and 13 percent of tea partyers thought that view was justified, but those numbers increased to 26 percent of independents, 28 percent of Democrats, 24 percent of moderates, and 40 percent of liberals. (It should be noted that a majority in all these groups nonetheless said that a negative opinion of the U.S. was unjustified.) Solid majorities of Republicans, conservatives, white evangelicals, and tea partyers believe that people claiming to be Muslim who commit acts of violence in the name of Islam are nonetheless true Muslims; no such majority exists among their counterparts on the other side. It is hard to resist the conclusion that attitudes toward Muslims have become an integral part of the cultural conflict suffusing American politics today.

Indeed, much of the same can be said about attitudes toward pluralism in general. It is not surprising to learn that Republicans, conservatives, and tea party identifiers are more concerned about illegal immigration than are other Americans and that they are more likely to favor harsher policy responses such as deportation. It is more surprising to learn that majorities of these three groups agree that the “growing number of newcomers from other countries threatens traditional American customs and values.” While Democrats and Republicans, liberals and conservatives, tea party and non-tea party agree that newcomers are changing “your community and ways of life,” their evaluations of this fact differ sharply. Majorities of Republicans, conservatives, tea partyers, and white evangelicals who thought immigrants were changing American communities believe that these changes are for the worse. Majorities of Democrats, liberals, and non-tea partyers who thought immigrants were bringing about changes viewed that positively.

Age and education both have a major impact on judgments about increasing diversity. Eighty-six percent of young adults and 77 percent of those over age 65 thought immigrants were changing their communities. Of those, 68 percent of young adults think that it is a good thing, a figure that falls to only 36 percent for those over age 65. Similarly, only 44 percent of those with a high school education or less say the changes they see are a good thing, versus 64 percent of college graduates and 70 percent of those with postgraduate training.

There is evidence of comparable differences on some racial issues. For example, Republicans, conservatives, and tea partyers are much less likely than are others to believe that discrimination against minority groups is a critical issue facing the country. By contrast, 60 percent of Republicans, 56 percent of conservatives, and 63 percent of tea party sympathizers agree that “Today discrimination against whites has become as big a problem as discrimination against blacks and other minorities,” a proposition that their ideological and partisan counterparts reject. While it is a mistake to infer that majorities of these groups harbor racist beliefs and motives, they plainly have views about the state of contemporary race relations that differ from those of many other Americans.

VIII. Immigration & The Partisan Divide

The polarization traced in the previous section extends to immigration reform, once a cause that crossed partisan lines. As recently as 2007, the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act was introduced with bi-partisan support—notably from President George W. Bush and Senator John McCain and liberal stalwart Senator Ted Kennedy. It was the last serious push in Congress for a law that would regularize the status of immigrants who entered the United States illegally.

This survey suggests that bi-partisanship on the issue will be increasingly difficult, one reason why immigration reform continues to founder. The issue has fallen prey to the same forces of partisan and ideological division that have polarized both public opinion and behavior in Congress on so many other questions.

On its face, immigration reform still enjoys majority support. As our colleagues noted earlier in this report, several measures point in this direction. For example, 56 percent said they favored “allowing undocumented immigrants who have been in the U.S. for several years to earn legal working status and an opportunity for citizenship in the future.” Forty-one percent were opposed.

But most Americans do not hold strong views on this issue—and among those who do, opponents of immigration reform outnumber supporters. Only 14 percent strongly favored allowing undocumented immigrants to earn legal status and an opportunity for citizenship, while 19 percent were strongly opposed. These numbers do not bode well for congressional action: voters who feel strongly enough about immigration to consider it when they cast their ballots seem, on balance, more likely to punish supporters of reform.

And this question divides the parties. Overall, Republicans opposed immigration reform, though narrowly, 53 percent to 46 percent. A strong majority of Democrats favored it, 67 percent to 30 percent, while independents favored reform by 55 to 42 percent. Conservative views were consistent with those of Republicans’ (53 percent opposed to immigration reform), while 59 percent of tea party members opposed reform. Among liberals, 74 percent favored reform, as did 59 percent of moderates.

Those with strong views divided even more sharply. Only 6 percent of Republicans, 8 percent of conservatives and 8 percent of tea party members strongly favored immigration reform; but 21 percent of Democrats and 28 percent of liberals did. Similarly, only 11 percent of Democrats were strongly opposed to immigration reform, but 27 percent of Republicans were. Only 11 percent of liberals were strongly opposed but 25 percent of conservatives and 33 percent of tea party members were.

The survey posed a question that was a rough test of attitudes toward the DREAM Act, and the overall findings were similar to those on immigration reform: 57 percent favored “allowing illegal immigrants brought to the U.S. as children to gain legal resident status if they join the military or go to college;” 40 percent were opposed.

But on this issue, the intensity of feeling was quite different than on the more general reform question: 18 percent said they strongly favored the DREAM Act proposition; 16 percent were strongly opposed. Most of the shift in intensity came among conservatives (20 percent strong opposition versus 25 percent on the general immigration question); and tea party members (25 percent versus 33 percent). In principle, at least, reform ideas along the lines of the DREAM Act—partial solutions based on some concept of “earned” citizenship—are likely to provoke less intense hostility than broader proposals. They thus appear to have a better chance than other reform measures of passing.

The ambivalence in the country on the subject of immigration is one of the most powerful messages of the survey. On the one hand, immigrants have a relatively positive public image overall. The survey offered respondents a series of statements and asked if they described immigrants “very well,” “somewhat well,” “not too well,” or “not at all well.” Eighty-seven percent said “hardworking” described immigrants well, including 44 percent who said this described them “very well.” Eighty percent said immigrants had “strong family values,” including 42 percent who said this described them “very well.” On the other hand, 51 percent said the statement “They make an effort to learn English” described immigrants “not too well” or “not at all well.”

The tensions—one might also say contradictions—within American attitudes were brought home by two questions that measured opinions on the same subject in different ways. Offered the straightforward proposition, “We should make a serious effort to deport all illegal immigrants back to their home countries,” the country split down the middle: 51 percent agreed, including 22 percent who said they “completely agreed,” while 48 percent disagreed, including 17 percent who disagreed completely.

Once again, only about a third of the respondents took the strongest position available on one side or the other. Once again, those with the most strongly held positions titled toward the anti-immigration side. And once again, the question divided by party and ideology.

Among Republicans, 68 percent supported a serious effort to deport all immigrants, including 31 percent who completely agreed. Among Democrats, 40 percent agreed and only 16 percent completely agreed. Among conservatives, 65 percent agreed (29 percent completely), while among tea party members, 72 percent agreed, including 37 percent who agreed completely. Among liberals, only 32 percent favored deportation, 12 percent of them completely agreeing.

Yet a different question, laying out an alternative to deportation, produced a strikingly different result, as our colleagues emphasized earlier. Respondents were asked to choose between two statements as to which was “the best way to solve the country’s illegal immigration problem.” The first proposed “to secure our borders and arrest and deport all those who are here illegally.” The second proposed “to secure our borders and provide an earned path to citizenship for illegal immigrants already in the U.S.”

Presented with this formulation, support for deportation dropped to 36 percent. The second statement was preferred by 62 percent of respondents. Across partisan and ideological lines, the only group that still produced a majority for deportation on this form of the question were tea party members, 57 percent of whom preferred the “arrest and deport” alternative.

When presented with an alternative, the sharpest drop in support for deportation came among Republicans and moderates. Question wording made the least difference to independents and liberals.

The unsettled state of opinion on immigration does suggest that there is considerable room for persuasion and leadership. But the sharp partisan and ideological polarization around the issue complicates the task of leadership, particularly for a Democratic President who supports immigration reform. And as long as the tea party maintains its considerable sway over Republican elected officials, compromise will be very difficult to achieve because the pressure on Republicans to oppose it will remain high.

IX. The Mormon Factor

Public acceptance of Mormons continues to lag well behind formerly marginalized religious groups such as Jews and Catholics, who enjoy 84 and 83 percent approval, respectively. Still, 67 percent of Americans have wholly or mostly favorable views of Mormons, while only 20 percent express unfavorable views. Young adults are more likely than others to express disapproval of Mormons, perhaps because Mormons have been highly visible in their opposition to same-sex marriage, which enjoys strong support among the young.

One of the survey’s fascinating findings is that hostility to Mormons is roughly equal among conservatives and liberals—21 percent of conservatives express an unfavorable view, as do 22 percent of liberals. (Among moderates, 19 percent have an unfavorable view.) Just as there were left- and right-wing versions of anti-Catholic feeling in the past, so there are now two ideological streams of opposition to Mormons. What is not true is that conservatives are especially hostile to Mormons, a hypothesis based on the idea that white evangelicals, most of them conservative, feel the greatest theological distance from Mormons.

Our survey does not support this hypothesis. Approval of Mormons among Republicans overall stands at 74 percent, 9 points higher than among Democrats. It is 69 percent among conservatives and 78 percent among tea party identifiers. And most strikingly, it is 66 percent among white evangelicals—slightly lower than for Republicans and the country as a whole, but still high.

Conventional wisdom is right in one respect: while 47 percent of the population, 49 percent of Republicans, 45 percent of conservatives, and 52 percent of tea partyers think that Mormonism is a Christian religion, only 34 percent of white evangelicals share that view. The mistake is to infer that because white evangelicals overwhelmingly exclude Mormons from the Christian fold, they must necessarily disapprove of them. No doubt some do. But it appears that Mormons’ family life, work ethic, traditional values, and pronounced conservative leanings do more to shape evangelical attitudes toward them than does their theology. The principal question facing Mitt Romney and Jon Huntsman over the next nine months is not whether they are Christian, but whether they are sufficiently and reliably conservative.

X. The Millennial Difference: Age & Education

Previous surveys have suggested that young people are more accepting of America’s rapidly increasing religious and ethnic diversity than are their parents and grandparents. For the most part, this survey confirms that proposition, with a few intriguing twists. It also suggests that education is often as important as age in shaping individual outlooks on these issues.

Young people are more likely to express very favorable views of African-Americans and Hispanics, as are those with a high level of education. As for views of Muslims, 68 percent of young adults ages 18 to 29 express positive views, versus only 46 percent of those 65 and older. More highly educated Americans are also especially likely to dissent from suspicious or negative views toward Muslims. For example, 70 percent of both Americans under age 30 and those with a bachelor’s degree or more reject the idea that Muslims seek to institutionalize shari’a. Similarly, younger and more educated Americans are less likely to see a conflict between Islam and American values. Of respondents who thought people in Muslim countries had an unfavorable opinion of the U.S., younger Americans were almost three times as likely as the elderly to see those opinions as justified, while those with postgraduate education were 13 percentage points more likely to adopt this view than were those with a high school diploma or less. Sixty-two percent of young adults and 72 percent of those with postgraduate training see Muslims as an important part of the U.S. religious community, versus 44 percent of seniors and 46 percent of those who have gone no further than high school.

These attitudes are correlated with patterns of social relations. Younger and more educated Americans are more likely to report regular conversations with African-Americans, Hispanics, and Muslims than are the older and less educated. Whether these attitudinal differences precede or flow from regular contact is hard to say, but a fair amount of sociological research has found a causal connection between familiarity with those unlike ourselves and comfort with social differences.