Citizenship, Values, and Cultural Concerns: What Americans Want from Immigration Reform

Executive Summary

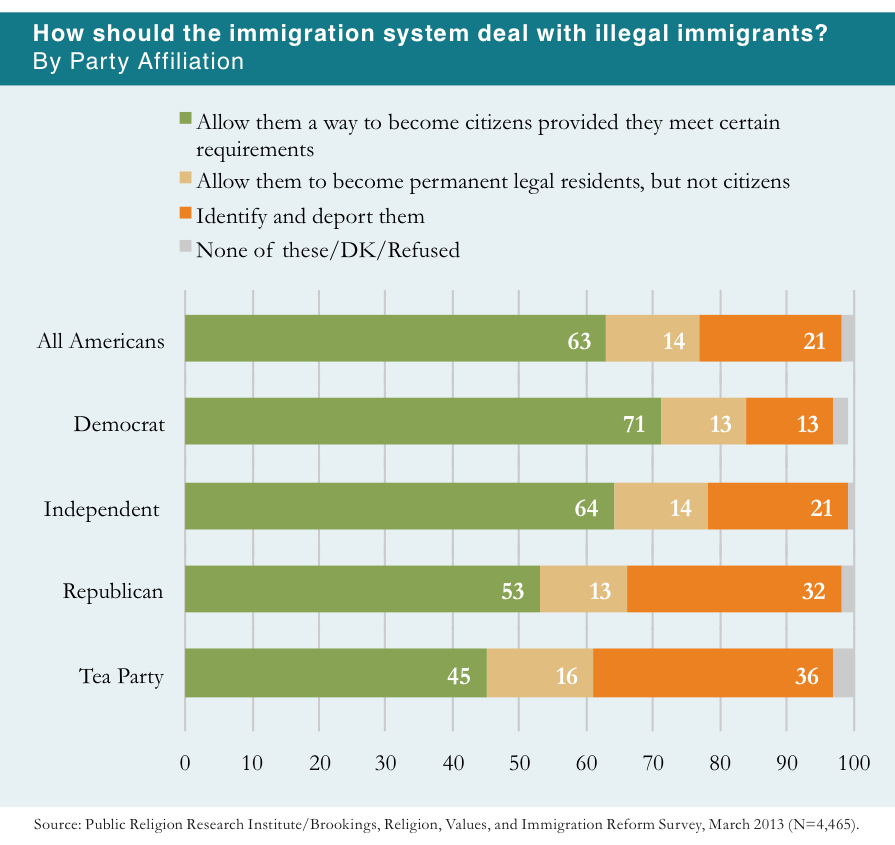

More than 6-in-10 (63%) Americans agree that the immigration system should deal with immigrants who are currently living in the U.S. illegally by allowing them a way to become citizens, provided they meet certain requirements. Less than 1-in-5 (14%) say they should be permitted to become permanent legal residents, but not citizens, while approximately 1-in-5 (21%) agree that they should be identified and deported.

More than 6-in-10 (63%) Americans agree that the immigration system should deal with immigrants who are currently living in the U.S. illegally by allowing them a way to become citizens, provided they meet certain requirements. Less than 1-in-5 (14%) say they should be permitted to become permanent legal residents, but not citizens, while approximately 1-in-5 (21%) agree that they should be identified and deported.

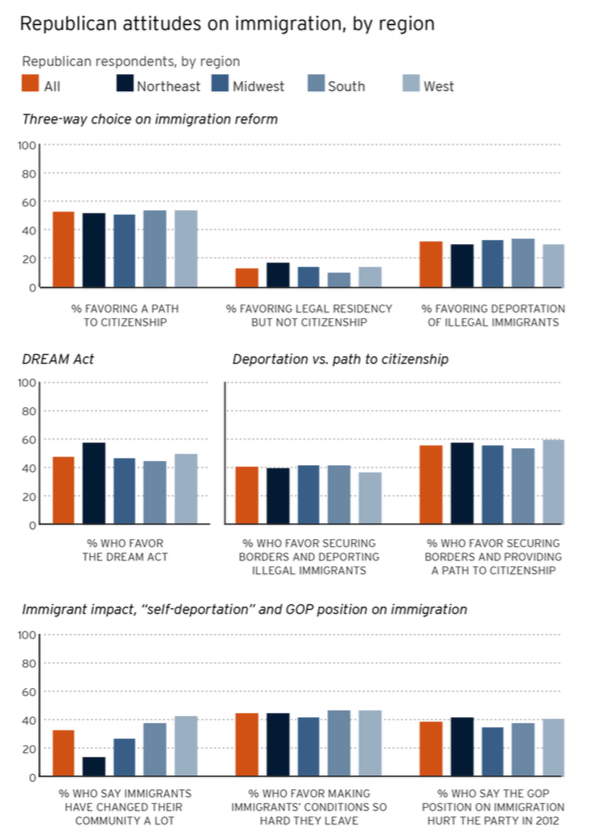

- More than 7-in-10 (71%) Democrats, nearly two-thirds (64%) of independents, and a majority (53%) of Republicans favor an earned path to citizenship. Similar numbers of Democrats (13%), independents (14%), and Republicans (13%) favor a path to legal residency, but not citizenship. Meanwhile, 13% of Democrats, 21% of independents, and 32% of Republicans favor deportation.

- Majorities of all religious groups, including Hispanic Catholics (74%), Hispanic Protestants (71%), black Protestants (70%), Jewish Americans (67%), Mormons (63%), white Catholics (62%), white mainline Protestants (61%), and white evangelical Protestants (56%) agree that the immigration system should allow immigrants currently living in the U.S. illegally to become citizens provided they meet certain requirements.

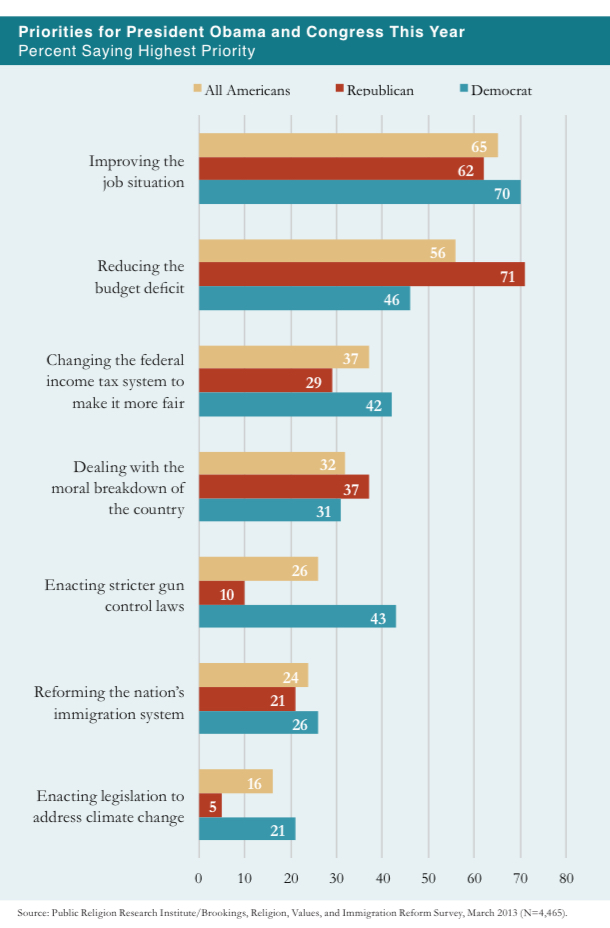

Americans rank immigration reform sixth out of seven issues, far behind economic issues, as the highest political priority for the president and Congress. Less than one-quarter (24%) of Americans say that reforming the nation’s immigration system should be the highest priority for the president and Congress, while 47% of Americans report that reforming the immigration system should be a high priority but not the highest, and nearly 3-in-10 (27%) think that immigration reform should be given a lower priority.

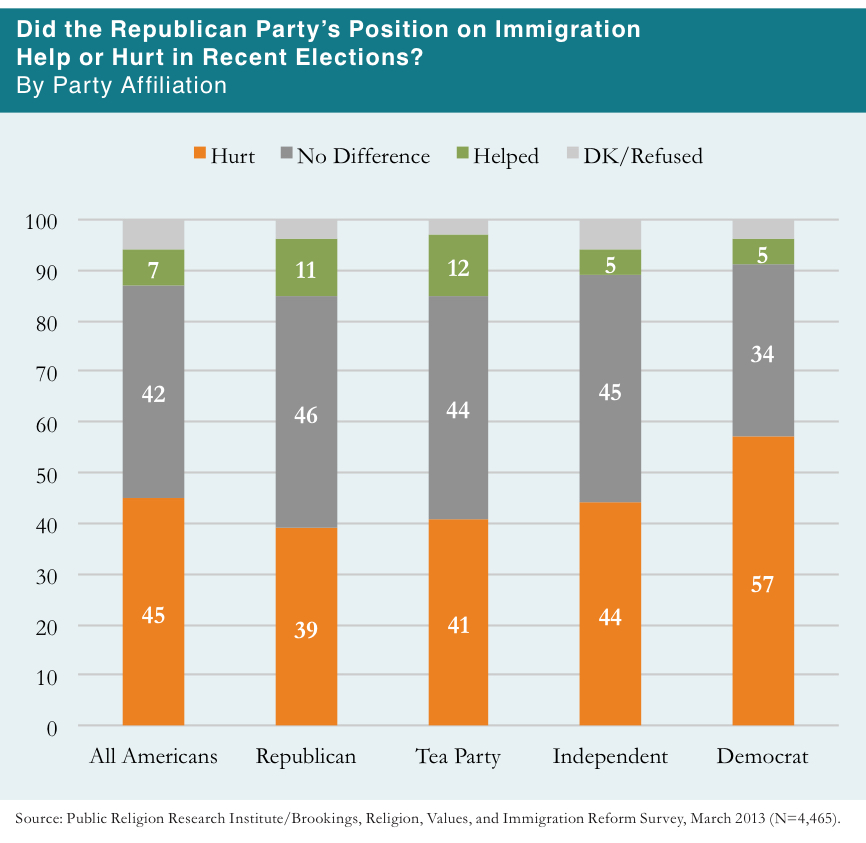

Nearly half (45%) of Americans say the Republican Party’s position on immigration has hurt the party in recent elections. Less than 1-in-10 (7%) Americans say that the Republican Party’s stance on immigration has helped them in recent elections, while more than 4-in-10 (42%) say it has not made a difference.

- Approximately 4-in-10 Republicans (39%) and Americans who identify with the Tea Party (41%) think the Republican Party’s position on immigration has hurt the party in recent elections. Close to half (46%) of Republicans and a similar number of Tea Party members (44%) say it did not make a difference.

- About 4-in-10 (39%) Hispanic Americans overall say the Republican Party’s position on immigration hurt the party in the 2012 election. Approximately 4-in-10 (41%) say it did not make a difference, and 14% say it helped the Republican Party.

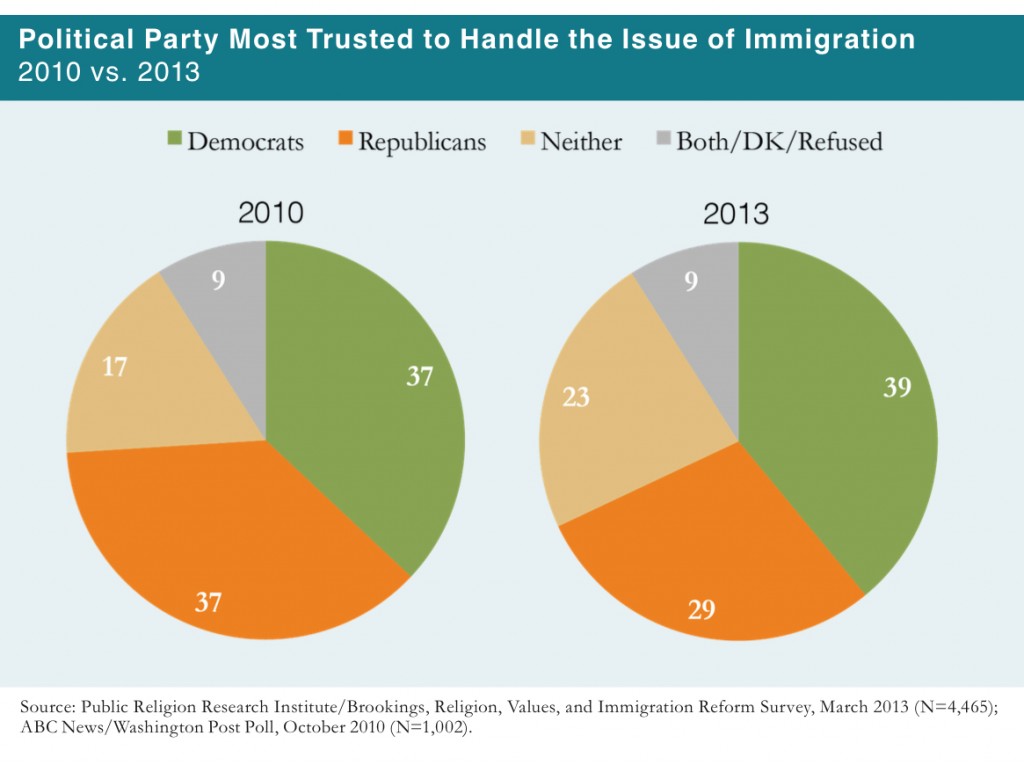

Americans are more likely to say they trust the Democratic Party, rather than the Republican Party, to do a better job handling the issues of immigration (39% vs. 29%) and illegal immigration (43% vs. 30%). However, nearly 1-in-4 (23%) Americans say they do not trust either party to handle the issue of immigration.

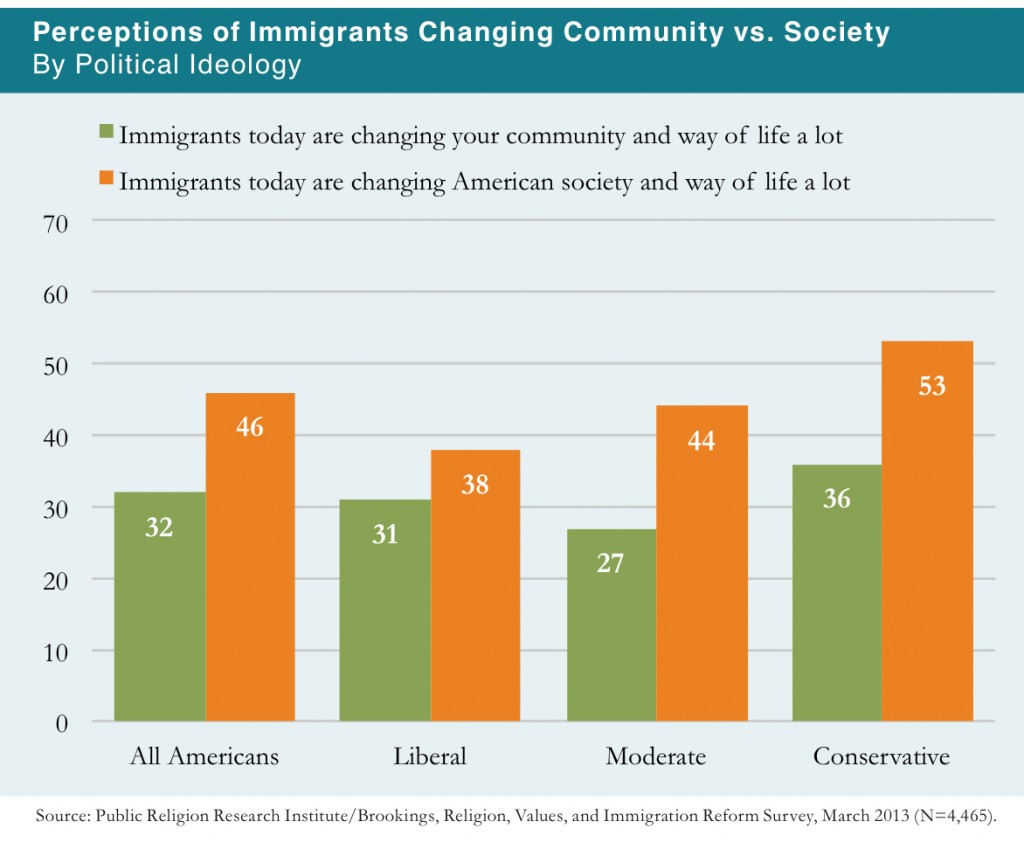

Americans generally perceive that immigrants are having more of an impact on American society as a whole than on their own communities. Less than one-third (32%) of Americans say that immigrants today are changing their community a lot, compared to 46% of Americans who say immigrants today are changing American society a lot.

- Views about immigrants’ impact on American society are strongly associated with political ideology. Conservatives (36%) and liberals (31%) are nearly equally as likely to say that immigrants are changing their own communities a lot. However, conservatives (53%) are significantly more likely than liberals (38%) to say that immigrants are changing American society a lot.

Overall, Americans are more likely have positive rather than negative views about the impact of immigrants.

- A majority (54%) of Americans believe that the growing number of newcomers from other countries helps strengthen American society, while a significant minority (40%) say that newcomers threaten traditional American customs and values.

- A strong majority (59%) of Americans believe that immigrants today see themselves as part of the American community, much like immigrants from previous eras, while 36% disagree.

Americans register some concerns about the economic impact of immigrants. While nearly two-thirds (64%) of Americans agree that immigrants coming to this country today mostly take jobs that Americans don’t want, a majority (56%) of Americans simultaneously say that illegal immigrants hurt the economy by driving down wages for many Americans.

Although deportations of illegal immigrants have increased since the beginning of the Obama administration, less than 3-in-10 (28%) Americans correctly state that deportations have increased over the past five or six years. A plurality (42%) of Americans believe that the number of deportations has stayed the same, while nearly 1-in-5 (18%) say deportations have decreased.

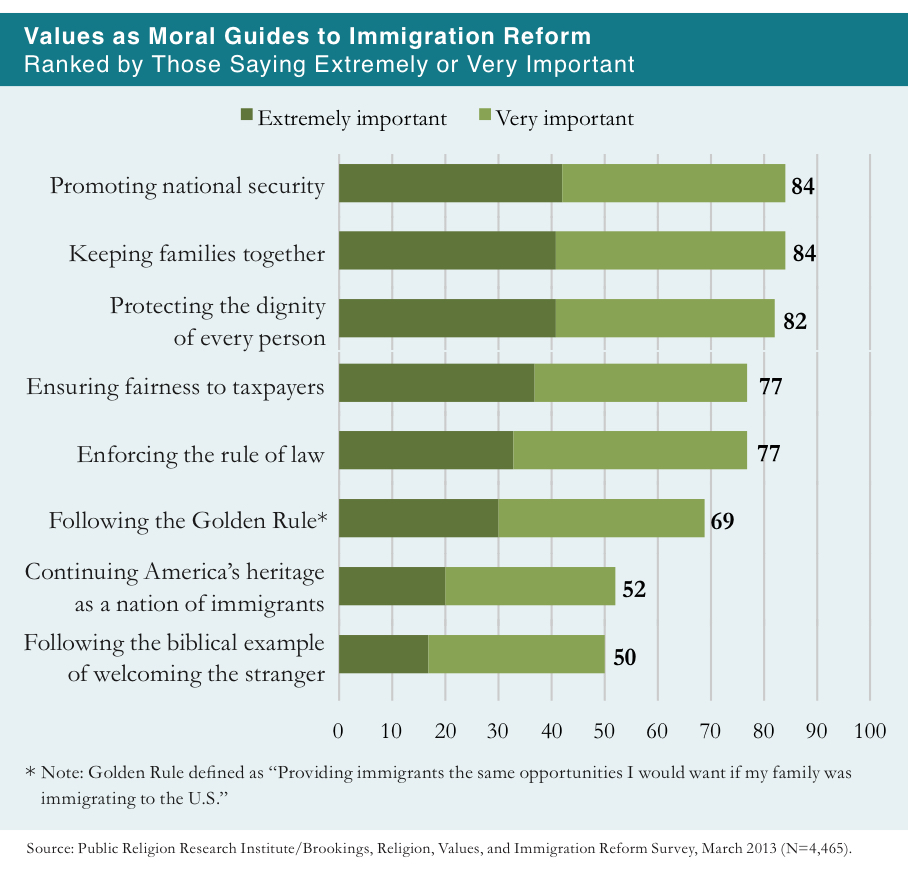

There is broad agreement about a set of values that should guide immigration policy.

- Five values are rated very or extremely important as guides to immigration reform by approximately 8-in-10 Americans: promoting national security (84%), keeping families together (84%), protecting the dignity of every person (82%), ensuring fairness to taxpayers (77%), and enforcing the rule of law (77%).

- Nearly 7-in-10 (69%) also say following the Golden Rule—“providing immigrants the same opportunity that I would want if my family were immigrating to the U.S.”—is a very or extremely important value.

Far fewer Americans say continuing America’s heritage as a nation of immigrants (52%) or following the biblical example of welcoming the stranger (50%) are very or extremely important guides for immigration reform.

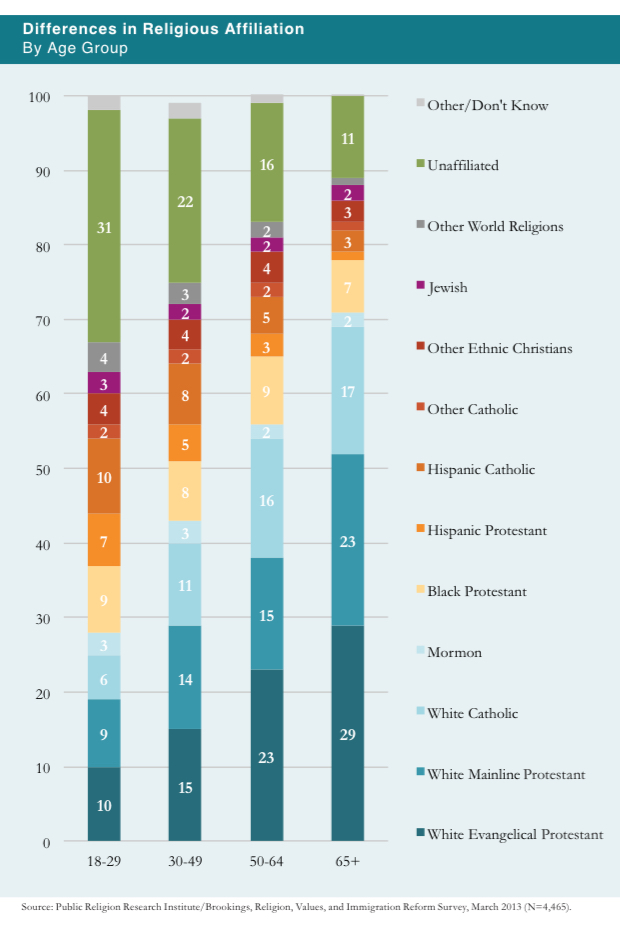

The face of American society has changed dramatically over the course of a single generation. More than 7-in-10 (71%) seniors (age 65 and older) identify as white Christian (29% white evangelical Protestant, 23% white mainline Protestant, and 17% white Catholic). By contrast, less than 3-in-10 (28%) Millennials (age 18-29) identify as white Christian (10% white evangelical Protestant, 9% white mainline Protestant, and 6% white Catholic).

Demographic differences are reflected in sharply contrasting evaluations of how American culture and way of life has changed since the 1950s. A majority (54%) of Americans say that since the 1950s, American culture and way of life has mostly changed for the worse, while 4-in-10 (40%) say it has mostly changed for the better.

- There are significant racial divisions, with 61% of white Americans reporting that American culture has changed for the worse, while majorities of black (56%) and Hispanic Americans (51%) report that things have changed for the better.

When asked directly, only about 1-in-10 white, non-Hispanic Americans say they agree that the idea of an America where most people are not white bothers them, but when asked indirectly in a controlled survey experiment, agreement rises to nearly one-third (31%).

More than 6-in-10 (61%) Americans favor allowing illegal immigrants brought to the U.S. as children to gain legal resident status if they join the military or go to college, a policy which comprises the basic elements of the DREAM Act. Approximately one-third (34%) of Americans oppose to this policy.

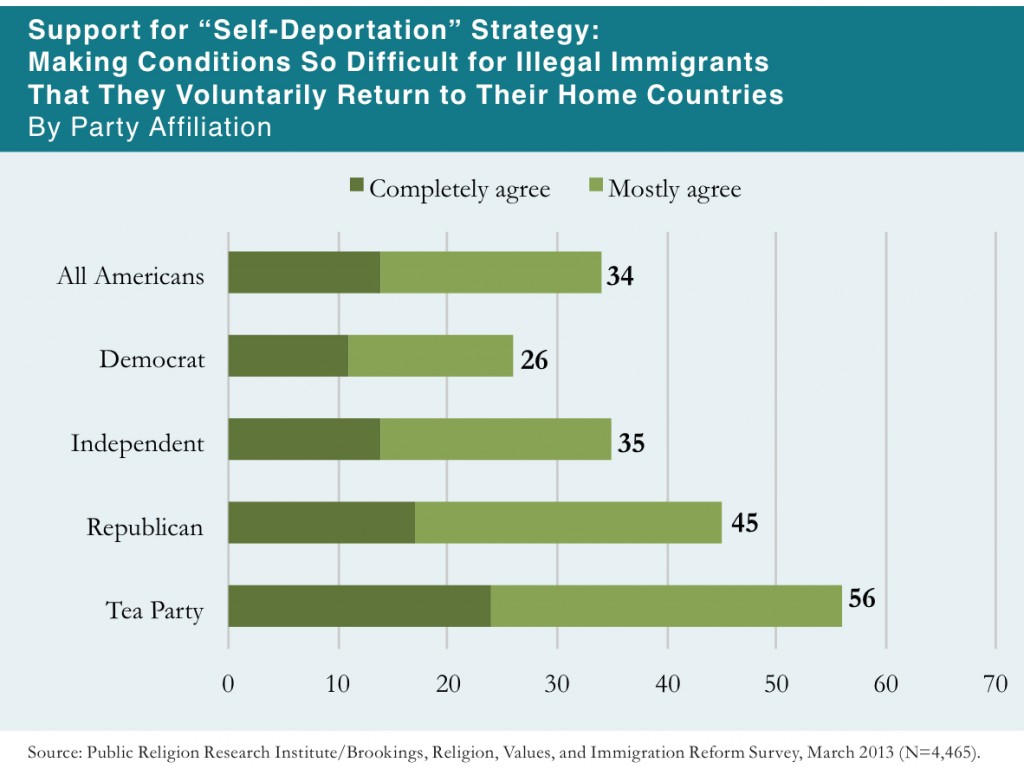

Few Americans favor a policy colloquially known as “self-deportation,” in which conditions are made so difficult for illegal immigrants that they return to their home country on their own. Approximately one-third (34%) of Americans agree that this is the best way to solve the country’s illegal immigration problem, while nearly two-thirds (64%) disagree.

I. Introduction

Since 2006, when the bipartisan efforts of President George W. Bush, Senator John McCain, and the late Senator Edward Kennedy failed to achieve comprehensive immigration reform legislation, the issue of immigration has been a perennial issue of public debate. Yet, despite Americans’ significant discontent with the current immigration system and their broad support for a comprehensive overhaul, immigration reform legislation has languished. Two developments succeeded in making the passage of comprehensive immigration reform less likely. First, the 2008 economic collapse dramatically reshuffled the governing priorities of both parties. For most Americans, the immigration issue ranks much lower than fixing the economy or reducing the budget deficit. Second, the 2010 congressional elections, which gave the GOP a strong majority in the House of Representatives, brought in a large class of Tea Party members who are generally strongly opposed to such legislation.

However, recent events have conspired to put immigration reform back on the legislative agenda. First, even before the 2012 presidential election, President Obama signaled that immigration reform would be the centerpiece of his second-term agenda. Second, the 2012 election demonstrated the growing clout of Hispanic voters, particularly in western battleground states. Obama’s lopsided margin among these voters provided strong incentives for both parties, but especially Republicans who had been opposed to immigration reform, to make immigration reform a more significant priority.

In February 2013, Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI), in partnership with the Brookings Institution, conducted one of the largest surveys ever fielded on immigration policy, immigrants, and religious and cultural changes in the U.S. The survey of nearly 4,500 American adults explores the many divisions—political, religious, ethnic, geographical, and generational—within the nation over core values and their relationship to immigration. The new survey also tracks key questions from surveys conducted by PRRI in 2010-2011.

II. The Political Context: Importance of Immigration Reform and Perceptions of Political Parties

Importance of Immigration Compared to Other Issues

Immigration reform may loom large on the legislative radar, but economic issues remain at the top of Americans’ political priorities. Majorities of Americans report that improving the job situation (65%) and reducing the budget deficit (56%) should be the highest priorities for President Obama and Congress. Immigration reform ranks sixth out of seven issues as the highest priority for Americans. Less than one-quarter (24%) of Americans rank reforming the nation’s immigration system as the highest priority for the president and Congress, while 47% of Americans report that reforming the immigration system should be a high priority but not the highest, and nearly 3-in-10 (27%) think that immigration reform should be given a lower priority. There are few partisan differences on the relative importance of immigration reform compared to other legislative priorities; however, there are some divisions by race and religious affiliation.

Among racial and ethnic groups, Hispanic Americans stand out in prioritizing immigration reform. Nearly half (46%) of Hispanic Americans say that reforming the nation’s immigration system should be the highest priority for the president and Congress, compared to about 3-in-10 (31%) black non-Hispanic Americans, more than 1-in-5 (22%) Asian Americans, and less than 1-in-5 (18%) white non-Hispanic Americans.(1)

These racial and ethnic differences are also visible among religious groups. Half (50%) of Hispanic Catholics think that reforming the nation’s immigration system should be politicians’ highest priority, while more than one-third (34%) think it should be a high priority but not the highest. Similarly, a plurality of Hispanic Protestants (43%) agree that reforming the immigration system should be the highest priority, while an additional 37% report that it should be a high priority, but not the highest.

Political Party Most Trusted to Handle Immigration

Americans are more likely to say they trust the Democratic Party to do a better job than the Republican Party in handling the issue of immigration (39% vs. 29%). However, nearly 1-in-4 (23%) Americans say they do not trust either party to handle the issue. The public expresses similar sentiment when the issue is illegal immigration. The Democrats have a modest advantage over Republicans (43% vs. 30%), while roughly 1-in-5 (19%) Americans report that they do not trust either party to handle the issue.

In 2010, Americans placed roughly equal trust in the two parties’ ability to handle the issue of immigration. Approximately 4-in-10 (37%) Americans reported trusting the GOP over the Democrats, and 37% said they trusted the Democratic Party over the Republicans.(2) Thus, the current Democratic advantage on this issue is due primarily to an eight-point drop in trust of the Republican Party on the issue over the past three years.

Trust in both parties’ ability to handle the issue of immigration is highly politically polarized. Strong majorities of Democrats (84%) and Republicans (75%) trust their respective parties to do a better job handling the issue of immigration. Independents are roughly divided over whether they place more trust in the Democrats (27%) or Republicans (23%) on the issue of immigration. Nearly 4-in-10 (38%) independents say they do not trust either party to handle the immigration issue. Interestingly, Americans who identify with the Tea Party (62%) are significantly less likely than Republicans overall to report that they place more trust in the Republican Party’s ability to handle immigration. Nearly 3-in-10 (28%) say they don’t trust either party on the issue.

Liberals have more faith in the Democratic Party (65%) on the issue of immigration than conservatives have in the Republican Party (48%). More than 1-in-5 (21%) conservatives say they trust the Democratic Party more than the Republican Party on the issue of immigration.

Religious groups are divided over which political party they trust to do a better job handling the issue of immigration. Seven-in-ten (70%) black Protestants say they place more trust in the Democratic Party’s ability to handle immigration. A plurality of religiously unaffiliated Americans (46% vs. 22%) and Catholics (43% vs. 27%) also say they trust the Democratic Party over the Republican Party to handle immigration. Among Catholics, there is a significant ethnic divide: Hispanic Catholics are much more likely to trust the Democratic Party over the Republican Party (59% vs. 14%), while white Catholics are nearly evenly divided (34% vs. 35%).(3) White mainline Protestants are also nearly evenly divided between the parties: one-third (33%) trust the Democrats, 30% trust the Republicans, and 29% say they trust neither party. By contrast, a majority (52%) of white evangelical Protestants say they place more trust in the Republican Party on the issue of immigration, while 18% say they trust the Democratic Party.

There are similar divides by race and ethnicity.(4) Two-thirds (67%) of black Americans say they trust the Democratic Party to do a better job handling the issue of immigration, as do a majority (54%) of Hispanic Americans. Less than 1-in-5 (19%) Hispanic Americans say they trust the GOP more than the Democrats on this issue. White Americans are more divided: 36% trust the Republican Party more on the issue of immigration, while 32% say they trust the Democratic Party.

Political Impact of the Republican Party’s Position on Immigration

Close to half (45%) of Americans say the Republican Party’s position on immigration has hurt the party in recent elections. Less than 1-in-10 (7%) Americans say that the Republican Party’s stance on immigration has helped it in recent elections, while more than 4-in-10 (42%) say it has not made a difference.

Approximately 4-in-10 Republicans (39%) and Americans who identify with the Tea Party (41%) think their party’s position on immigration has hurt the party in recent elections. Nearly half (46%) of Republicans and 44% of Tea Party members say it has not made a difference, and roughly 1-in-10 Republicans (11%) and Tea Party members (12%) believe it has helped the party.

Democrats are more likely than Republicans to believe that the GOP’s position on immigration has hurt the party in recent elections. Nearly 6-in-10 (57%) Democrats think the GOP has been hurt by its position on immigration, while more than one-third (34%) say that it has not made a difference, and only 1-in-20 (5%) think it has helped.

More than 4-in-10 (44%) independents say the Republican Party has been hurt by its position on immigration. A similar number of independents (45%) say the Republican Party’s position on the issue of immigration has not affected its electoral performance in recent elections, while only 5% say it has helped the party.

Religious groups differ on the extent to which the Republican Party was helped or hurt by its position on immigration in recent elections. More than 6-in-10 (63%) Jewish Americans,(5) a majority (53%) of white mainline Protestants, and nearly half (49%) of religiously unaffiliated Americans say the GOP has been hurt by its position on immigration in recent elections. Black Protestants (44% vs. 42%) and white evangelical Protestants (41% vs. 46%) are roughly equally as likely to say the issue of immigration hurt the Republican Party as they are to say it did not make a difference. White Catholics (46% hurt, 45% no difference) and Hispanic Catholics (43% hurt, 38% no difference) are similarly divided.

There are notable divisions on this question by race and ethnicity. About 4-in-10 (39%) Hispanic Americans say the GOP’s position on immigration hurt it in the 2012 election, while approximately 4-in-10 (41%) say it did not make a difference, and 14% say it helped the Republican Party, considerably more than white Americans (5%) and black Americans (7%).

III. The Social Context: Experience with Immigrants and Immigration

Community Context

Number of Immigrants in Local Community

Americans’ exposure to new immigrants varies considerably. Roughly equal numbers say they live in a community with many new immigrants (24%), some new immigrants (23%), only a few new immigrants (23%) or almost no new immigrants (27%). There are no large political or regional differences on this question. However, there are significant divisions by community type, race and ethnicity, religious affiliation, and generation.

A majority (53%) of Americans who live in urban areas say their community has some or many new immigrants, compared to less than one-third (32%) of Americans who live in rural areas.

Asian Americans are more likely than other racial and ethnic groups to report that they live in a community with some or many new immigrants. Nearly two-thirds Asian Americans (66%) say they live in a community with some or many new immigrants, compared to a slim majority (51%) of Hispanic Americans, nearly half (46%) of white Americans, and 4-in-10 (40%) black Americans. Majorities of black (57%) and white (51%) Americans report that they live in a community with only a few new immigrants or almost no new immigrants.

Proximity to immigrants varies by religious affiliation: Mormons (59%), Hispanic Catholics (53%), religiously unaffiliated Americans (51%), and Jewish Americans (51%) are somewhat more likely than white Catholics (44%), white mainline Protestants (44%), white evangelical Protestants (43%), and black Protestants (35%) to report that they live in a community with some or many new immigrants.

There are also some divisions by generation. A majority (51%) of Millennials (age 18-29) report that they live in a community with some or many new immigrants, compared to 36% of seniors (age 65 and older). More than 6-in-10 (61%) seniors say they live in a community with only a few new immigrants or almost no new immigrants.

Frequency of Contact With People Who Speak Little or No English

Fully half (50%) of Americans say they often come in contact with immigrants who speak little or no English. About one-quarter (26%) say they sometimes interact with immigrants who speak little or no English, and less than one-quarter say they rarely (18%) or never (5%) come in contact with immigrants who speak little or no English.

There are few political divisions on this question. However, Hispanic Americans (65%) are more likely than black (48%), white (47%), or Asian (41%) Americans to report that they come in contact with immigrants who speak little or no English often.

Hearing About Immigration in Church

Most religious Americans are not hearing frequently about the issue of immigration in church. Among those who attend church at least once or twice a month, roughly 1-in- 5 say their clergy leader speaks about the issue of immigration sometimes (16%) or often (6%). About one-quarter (27%) of regular church attenders say that their clergy leader speaks about the issue of immigration rarely, and nearly half (49%) report that their clergy leader never speaks about the issue of immigration.

Hispanic Catholics (54%) are the only religious group among whom a majority report that their clergy leader speaks about the issue of immigration sometimes or often. Nearly 4-in-10 (38%) Hispanic Protestants (6) also say that they hear about immigration sometimes or often in church, although more than 6-in-10 say they hear about immigration rarely (16%) or never (46%). Majorities of black Protestants (51%), white evangelical Protestants (52%), and white mainline Protestants (56%) say their clergy leader never speaks out about the issue of immigration.

Similarly, nearly half (45%) of Hispanic Americans who attend church at least once or twice a month say their clergy leader speaks out about immigration sometimes or often, compared to 26% of black regular church attenders and 17% of white regular church attenders.

Friends and Family

Friends Born Outside the U.S.

More than 6-in-10 (61%) Americans say they have a close friend who was born outside the U.S., while nearly 4-in-10 (39%) say they do not. There are divisions on this question by religious affiliation, race and ethnicity, generation, class, region, and community type.

Although majorities of most religious groups report that they have a close friend who was born abroad, minority religious groups are more likely than other groups to report that this is true of them. Hispanic Catholics (86%), Jewish Americans (77%), Hispanic Protestants (75%), Mormons (69%), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (64%) are more likely than white Catholics (55%), white mainline Protestants (55%), white evangelical Protestants (52%), and black Protestants (47%) to say they have a close friend who was born outside the country. A majority (52%) of black Protestants say they do not have a close friend who was born outside the U.S.

Similarly, Asian (89%) and Hispanic (81%) Americans are more likely than white (57%) or black (52%) Americans to report that they have a close friend who was born outside the U.S.

Millennials (68%) are twenty percentage points more likely than seniors (48%) to say they have a close friend who was born outside the U.S. White college-educated Americans (68%) are also nearly twenty percentage points more likely than white working-class Americans (49%) to report that they have a close friend born outside the country, although this varies significantly by age.(7)

Americans who live in urban areas (65%) are also more likely than Americans who live in rural areas (48%) to say they have a close friend who was born outside the U.S. Meanwhile, Americans from the West (71%) and Northeast (66%) are more likely than Americans who live in the South (57%) and Midwest (52%) to report that they have a close friend who was born outside the country.

First, Second, and Third-Generation Americans

Most Americans (82%) are at least third-generation, which means that they were born in the United States to American-born parents. Four percent of Americans are second-generation, born in the U.S. to foreign-born parents. More than 1-in-10 (13%) Americans, meanwhile, are first-generation, meaning that they were born in another country.

There are sizeable divisions by race and ethnicity. Half (50%) of first-generation Americans are Hispanic, while slightly more than 1-in-5 (21%) are white, and approximately 1-in-10 are Asian (12%) or black (11%). Similarly, a plurality (44%) of second-generation Americans are Hispanic, while one-third (33%) are white, 12% are Asian, and 4% are black. The vast majority (75%) of third-generation Americans are white, while more than 1-in-10 (12%) are black, and less than 1-in-10 are Hispanic (7%) or Asian (1%).

Knowledge of Family’s Immigration Story

Nearly 7-in-10 Americans say they know the story of how their family first came to the U.S. somewhat (26%) or very (43%) well. Less than 3-in-10 (29%) say they know their family’s immigration story not too well or not at all well. There are few differences by political affiliation and generation. However, there are variations according to race and ethnicity, religious affiliation, and class.

Majorities of all racial and ethnic groups say they know the story of how their family came to the U.S. somewhat or very well. However, Asian (58%) and Hispanic (54%) Americans are more likely than black (44%) and white (39%) Americans to say that they know the story of how their family came to the U.S. very well.

Similarly, there are variations among religious groups. Hispanic Catholics (81%), Mormons (76%), Jewish Americans (76%), white Catholics (73%), and white mainline Protestants (70%) are more likely than white evangelical Protestants (63%) and black Protestants (59%) to say they know the story of how their family came to the U.S. somewhat or very well.

There are also gaps according to social class. White college-educated Americans (76%) are more likely than white working-class Americans (61%) to say they know the story of how their family first came to the U.S. somewhat or very well.

IV. The Cultural Context: Nostalgia and Perceptions of Immigrants in a Changing America

The Changing Racial and Religious Landscape

The face of American society has changed dramatically over the course of a single generation, in part due to new immigration, birth rates, and shifting patterns of religious affiliation. American society, which for most of its history has been predominantly white Christian, is quickly becoming a racially and religiously multi-cultural nation. Currently, 65% of Americans identify as white, non-Hispanic, 11% as black, non-Hispanic, 14% as Hispanic, 3% as Asian, and 7% as mixed race or some other race. However, these patterns mask dramatic differences by age.

The racial differences between seniors, America’s oldest adults, and Millennials, America’s youngest adults, are dramatic. More than 8-in-10 (82%) seniors (age 65 and older) identify as white, compared to 9% who identify as black, 5% as Hispanic, 1% as Asian and 4% as some other race or mixed race. By contrast, only a slim majority (52%) of Millennials (age 18-29) identify as white, while nearly one-quarter (23%) identify as Hispanic, 12% identify as black, 5% as Asian, and close to 1-in-10 (8%) as some other race or mixed race.

The religious differences between these two generations are equally strong. More than 7-in-10 (71%) seniors identify as some type of white Christian, including white evangelical Protestant (29%) white mainline Protestant (23%), or white Catholic (17%). In contrast, less than 3-in-10 (28%) of Millennials identify as white Christian (10% white evangelical Protestant, 9% white mainline Protestant, and 6% white Catholic). Seniors are about three times more likely than Millennials to identify as white Catholic (17% vs. 6%). Conversely, Hispanic Catholics make up a much larger proportion of Millennials (10%) than seniors (3%). Among Americans under the age of 30, the majority (56%) of Catholics are now Hispanic. One other important religious difference separating seniors and Millennials is the number of each who identify as religiously unaffiliated. Nearly one-third (31%) of Millennials identify as religiously unaffiliated, compared to roughly 1-in-10 (11%) seniors. Millennials (13%) are also about four times more likely than seniors (3%) to identify as atheist or agnostic.

Feelings of Nostalgia and Cultural Protectionism

Perceptions of Changes Since 1950’s

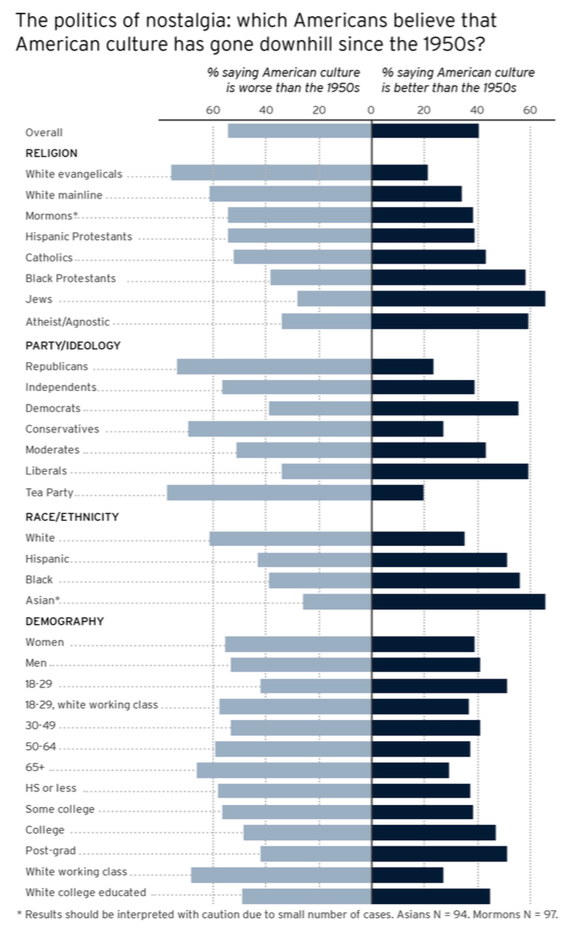

These significant demographic differences are reflected in sharply contrasting views about how American culture and way of life has changed since the 1950s. A majority (54%) of Americans say that since the 1950s, American culture and way of life has mostly changed for the worse, while 4-in-10 (40%) say it has mostly changed for the better. There are profound differences by political affiliation, religious affiliation, race and ethnicity, and generation. Notably, there are no significant differences by gender.

Political differences on this question are quite pronounced. Roughly three-quarters of Americans who identify with the Tea Party movement (76%) and Republicans (73%), as well as a majority (56%) of political independents, believe that American culture and way of life has changed for the worse. A majority (55%) of Democrats disagree, saying that American culture and way of life has changed for the better since the 1950s.

White Christians strongly embrace the belief that American culture has changed for the worse since the 1950s. Three-quarters (75%) of white evangelical Protestants and more than 6-in-10 white mainline Protestants (61%) and white Catholics (62%) say American culture and way of life has changed for the worse over the past half-century. Majorities of Hispanic Protestants (54%) and Mormons (54%) also agree that American culture and way of life has mostly changed for the worse. By contrast, nearly two-thirds of Jewish Americans (65%) and majorities of Hispanic Catholics (57%) and black Protestants (58%) believe that American culture has changed for the better.

There are also significant racial divisions, with 61% of white Americans reporting that American culture has changed for the worse, while majorities of Asian (65%), black (56%), and Hispanic (51%) Americans report that things have improved since the 1950s.

Nostalgic feelings about America’s past are much more apparent among those who lived during the 1950s. Nearly two-thirds (66%) of seniors believe that American culture has changed for the worse since that time, while a slim majority (51%) of Millennials say that American society has mostly changed for the better.

Concerns About Foreign Influence

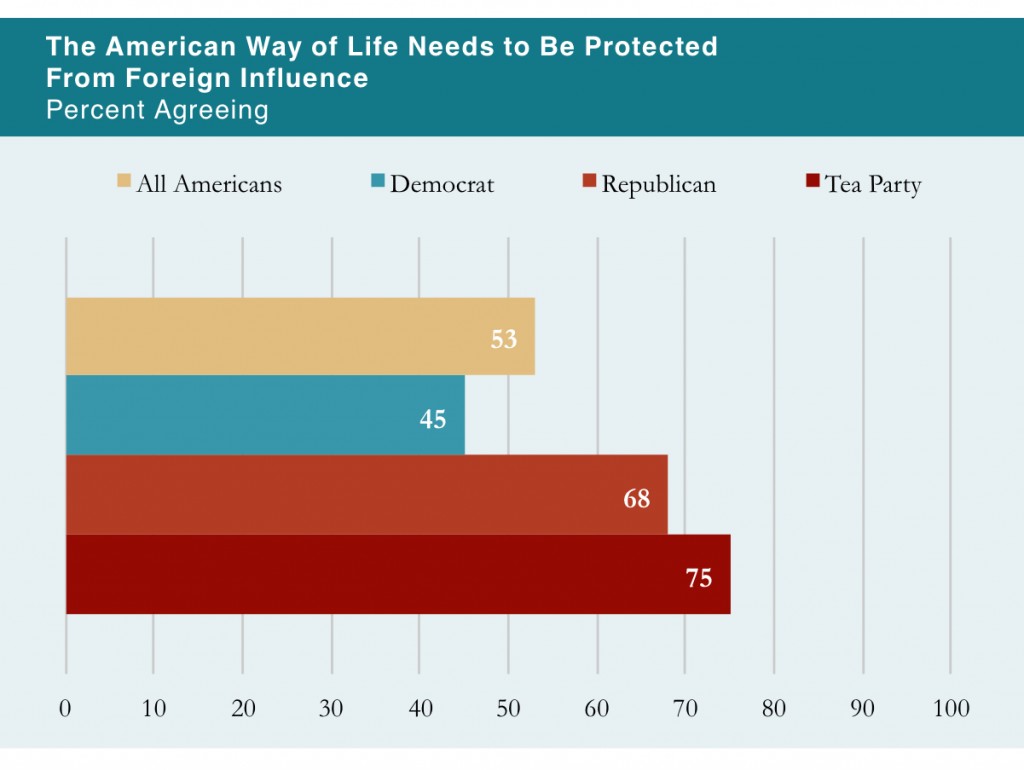

Americans are more divided over whether the American way of life needs to be protected against foreign influence: a majority (53%) agree, while 45% disagree. Political, religious and generational divisions on this question are substantial.

Nearly 7-in-10 (68%) Republicans agree that the American way of life needs to be protected, compared to roughly half of Democrats (45%) and independents (51%). Three-quarters (75%) of Americans who identify with the Tea Party believe that the American way of life needs to be protected, including nearly half (46%) who completely agree.

Most Christians, regardless of race or ethnicity, believe that the American way of life needs to be protected from foreign influence, including 69% of white evangelical Protestants, 65% of black Protestants, 59% of Hispanic Protestants, 57% of white Catholics, and 53% of white mainline Protestants. Hispanic Catholics are roughly evenly divided: half (50%) agree that the American way of life needs to be protected from foreign influence, while 46% disagree. Nearly 7-in-10 (68%) Jewish Americans, nearly 6-in-10 (58%) religiously unaffiliated Americans, and 52% of Mormons disagree that the American way of life needs to be protected from foreign influence.

There are also some generational divides. More than 6-in-10 (64%) seniors agree that the American way of life needs to be protected from foreign influence, compared to only 41% of Millennials.

Concerns About a Majority-Minority Nation

Despite feelings of nostalgia about mid-twentieth century culture, most Americans say that an idea of an America where the majority of the population is not white does not bother them. Only 14% of Americans report that they would be bothered by this notion, while more than 8-in-10 (84%) disagree. There are only modest differences by political affiliation. Less than 1-in-5 (18%) Republicans agree that a majority nonwhite America would bother them, compared to 14% of Democrats and 11% of independents. Nearly one-in-four (23%) Americans who identify with the Tea Party say that the idea of an America where most people are not white bothers them.

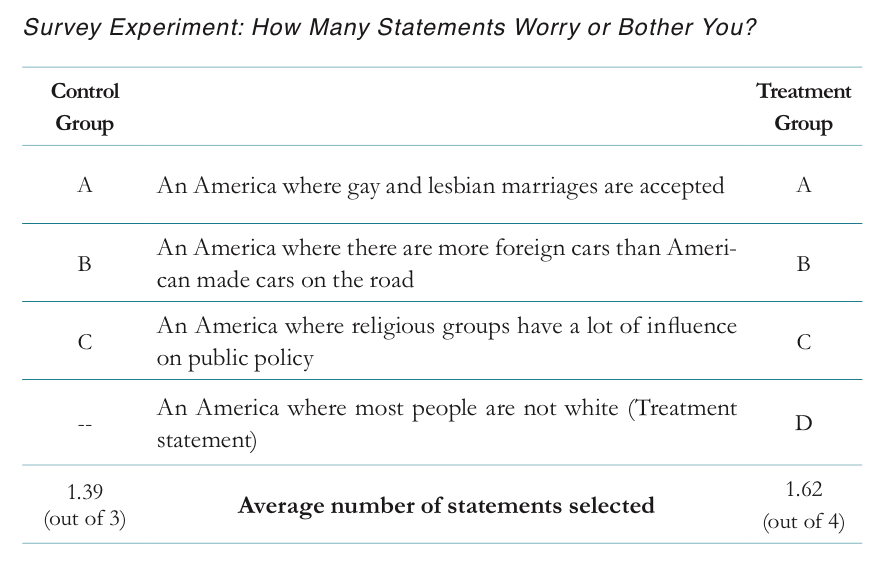

However, on issue of race, previous research (Sniderman and Carmines 1997) suggests that survey respondents may misrepresent their actual views on sensitive topics to live interviewers if these views are not consistent with what respondents believe is a socially desirable response. In order to measure whether a “social desirability effect” was operative when respondents were asked whether the idea of an America where most people are not white bothers them, a controlled experiment was conducted in a follow-up survey among a nationally representative sample of American adults (N=1,028).(8) The experiment, commonly known as a List Experiment, randomly divides the sample into two demographically identical groups, a control group and a treatment group. Each group was read a list of statements and instructed to report how many statements—not which specific statements—would bother or worry them. The first group was read a list of three control statements (A-C below), while the second group was read an identical list of statements with an additional fourth statement, the treatment statement: “An America where most people are not white.”

Thus, Americans who are reluctant to assert directly to an interviewer that an America where most people are not white bothers them were given a way to register this concern indirectly. Unless a respondent selected all four statements, which occurred in only 7% of all cases, they could be assured that the interviewer would not know which specific statements bothered them. Given that respondents were randomly assigned to the two groups, the only reason for a difference in the average number of statements selected by each group is the selection of the treatment statement. Therefore, by subtracting the average number of statements selected by the treatment group from the average number of statements selected by the control group, the experiment reveals an estimate of the percentage of Americans who are bothered by the idea of an America where most people are not white.

The List Experiment demonstrates that significantly more Americans overall are willing to say that the idea of an America where most people are not white bothers them when asked indirectly (23%), compared to when they are asked directly (14%). Among white non-Hispanic Americans, the gap between indirect and direct measures on this question doubles from 9 points to 18 points; only 13% of non-Hispanic whites say the idea of an American where most people are not white bothers them, but when given the opportunity to register this view indirectly, more than 3-in-10 (31%) do so.

The New American Community: Impact of Immigrants and Social Groups

Impact of Newcomers From Other Countries

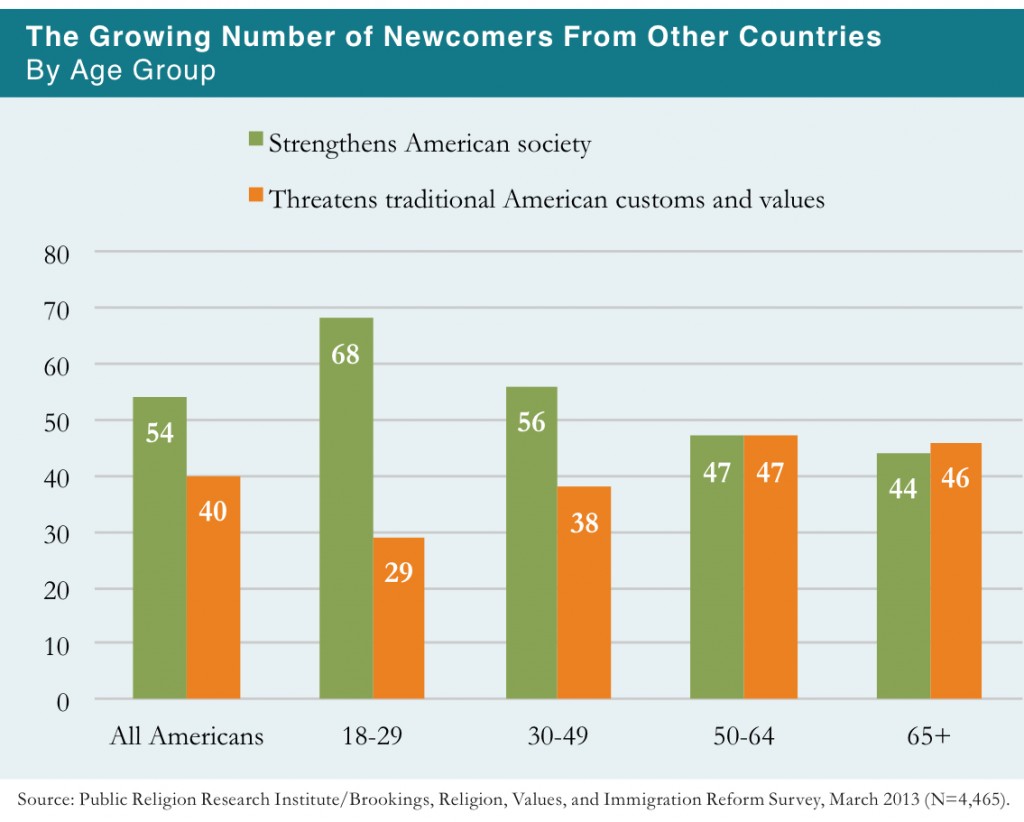

A majority (54%) of Americans believe that the growing numbers of newcomers from other countries help strengthen American society, while a significant minority (40%) say that newcomers threaten traditional American customs and values. Views about immigrants’ contributions have been stable since 2011, when 53% of the public believed that newcomers were strengthening American society.(9) However, there are yawning differences of opinion by political affiliation and generation.

Six-in-ten (60%) Americans who identify with the Tea Party and a smaller majority (55%) of Republicans believe that the growing number of newcomers from other countries threaten American customs. Nearly two-thirds (64%) of Democrats and a majority (54%) of independents believe the opposite—that the growing numbers of newcomers make America stronger.

Younger Americans exhibit more positive sentiments about the contributions of immigrants than do older Americans. Nearly 7-in-10 (68%) Millennials believe that immigrants coming to the U.S. strengthen society. By contrast, seniors are nearly evenly divided, with 46% saying that immigrants constitute a threat to traditional American customs and 44% saying that they benefit American society. These generational divides are also evident within the political parties. A majority (52%) of Millennial Republicans agree that immigrants strengthen American society, compared to only one-third (33%) of senior Republicans. There is an equally large generational divide among Democrats. Nearly three-quarters (74%) of Millennial Democrats say immigrants strengthen American society, compared to a smaller majority (52%) of senior Democrats.

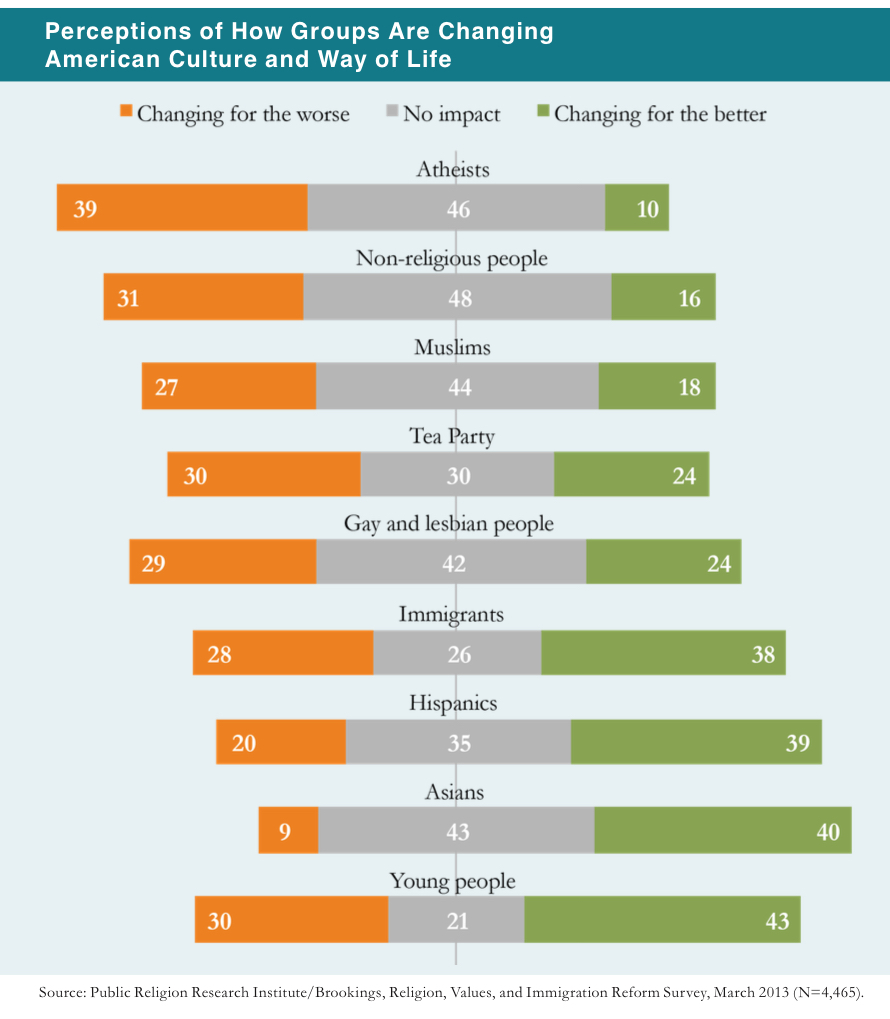

Influence of Groups on American Culture

Americans hold mixed views about certain social groups’ influence on American culture and way of life, and there are no groups whose effects are perceived to be wholly positive or negative. However, some groups, including Asians (40% better vs. 9% worse), Hispanics (39% better vs. 20% worse), immigrants (38% better vs. 28% worse), and young people (43% better vs. 30% worse), are viewed, on balance, as more likely to be changing American culture for the better than they are to be changing it for the worse.

On the other hand, by a nearly 4-to-1 margin, Americans believe that atheists are changing American culture for the worse (39%) rather than for the better (10%). There is roughly a 2-to-1 gap in views about the impact of non-religious people (31% worse vs. 16% better). The Tea Party (30% worse vs. 24% better), gay and lesbian people (29% worse vs. 24% better) and Muslims (27% worse vs. 18% better) are also perceived as having a somewhat more negative than positive impact on American culture and way of life.

There are sizable political differences in perceptions of these groups’ social impact. The biggest difference between Republicans and Democrats is, not surprisingly, in views of the Tea Party. Nearly half (47%) of Democrats say that the Tea Party is changing American culture and way of life for the worse, compared to 10% of Republicans. By contrast, nearly half (48%) of Republicans say the Tea Party is changing American culture and way of life for the better.

There are also political divisions in Americans’ perceptions of atheists, gay and lesbian people, immigrants, and Muslims. Nearly 6-in-10 (59%) Republicans say that atheists are changing American culture for the worse, compared to one-third (33%) of Democrats. Roughly half (49%) of Republicans say that gay and lesbian people are also changing American culture for the worse, compared to 1-in-5 (20%) Democrats. Republicans (40%) are also about twice as likely as Democrats (21%) to say that immigrants are changing American way of life for the worse. Americans who identify with the Tea Party do not differ substantially from Republicans in their views of most groups, with two exceptions. Members of the Tea Party are more likely than Republicans to say that Muslims (54% vs. 45%) and gay and lesbian people (57% and 49%) are changing American society for the worse.

The generational gaps are similarly substantial. Overall, Millennials are more likely than seniors to perceive all social groups, with the exception of the Tea Party, as having positive impact on American culture. The largest divides between Millennials and seniors are in views of atheists, gay and lesbian people, and Muslims. A majority (55%) of seniors say that atheists are changing American culture and way of life for the worse, compared to less than 1-in-4 (24%) Millennials. More than 4-in-10 (44%) seniors say that gay and lesbian people are changing American culture for the worse, compared to 14% of Millennials. There is a similar gap in views about Muslims, with 40% of seniors saying they are changing American culture for the worse compared to 12% of Millennials. Millennials (50%) are also more likely than seniors (37%) to see young people’s contribution to American culture as positive.

Impact of Immigrants on Local Communities and American Society

Americans generally perceive that immigrants are having more of an impact on American society than on their own communities. Less than one-third (32%) of Americans say that immigrants today are changing their community a lot, 46% say they are changing it a little, and roughly 1-in-5 (21%) say they are not having any impact. Meanwhile, close to half (46%) of Americans say immigrants today are changing American society a lot, 45% say they are changing it a little, and less than 1-in-10 (8%) say they are not having any impact.

Views about immigrants’ impact on American society are strongly associated with political ideology. Conservatives (36%) and liberals (31%) are about equally as likely to say that immigrants are changing their own communities a lot. However, conservatives (53%) are more likely than liberals (38%) to say that immigrants are changing American society a lot.

Americans who believe immigrants are having at last some impact are significantly more likely to say that immigrants’ influence on their own community is good (54%) rather than bad (37%). Views about immigrants’ impact on American society are more divided. Half (50%) of Americans say that these changes are a good thing, while more than 4-in-10 (41%) disagree, saying they are a bad thing. There are significant differences by political affiliation.

Among Americans who say that immigrants are changing their community at least a little, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to believe that immigrants’ influence on their community and American society more broadly is a good thing. Democrats (65%) are significantly more likely than Republicans (40%) or members of the Tea Party (30%) to say this influence is a good thing. Six-in-ten (60%) Americans who identify with the Tea Party and a majority (52%) of Republicans say this is a bad thing. The pattern of responses is similar in views about immigrants’ impact on American society as a whole.

Immigrants’ Perceptions of Themselves as Americans

Overall, nearly 6-in-10 (59%) Americans believe that immigrants today think of themselves as Americans, much like immigrants from previous eras, while 36% disagree.

Majorities of Democrats (66%), independents (59%), and Republicans (51%) agree that immigrants today think of themselves as Americans just as much as immigrants from earlier eras did. By contrast, 44% of Americans who identify with the Tea Party agree with this statement, while a majority (52%) disagree.

There are few racial differences on this question. More than 6-in-10 Asian (64%), black (64%), and Hispanic (63%) Americans believe that immigrants today are just as likely to think of themselves as Americans as immigrants from earlier eras did, as well as 57% of white Americans.

Majorities of all religious groups, including 68% of Jewish Americans, 66% of Hispanic Catholics, 64% of Hispanic Protestants, 63% of religiously unaffiliated Americans, 61% of black Protestants, 59% of white Catholics, 56% of white mainline Protestants, 54% of Mormons, and 51% of white evangelical Protestants, agree that immigrants today think of themselves as Americans just as much as immigrants from other eras did.

Interestingly, first-generation Americans (62%) are about equally as likely as second-generation (64%) and third-generation (58%) Americans to say that immigrants today think of themselves as Americans just as much as immigrants from earlier eras did.

Immigrants’ Impact on Jobs and the Economy

Although most Americans agree that immigrants coming to the U.S. today take jobs that most Americans don’t want, they also express significant concern about illegal immigrants’ effect on wages. Nearly two-thirds (64%) of Americans agree that immigrants coming to this country today mostly take jobs that Americans don’t want, while less than 1-in-3 (27%) say that immigrants take jobs away from American citizens. Meanwhile, a majority (56%) of Americans also agree that illegal immigrants hurt the economy by driving down wages for many Americans, while more than one-third (36%) say they help the economy by providing low-cost labor. There is a general consensus among political, racial, and religious groups that immigrants mostly take jobs that Americans don’t want. There is, however, less agreement among these groups on illegal immigrants’ overall effect on the economy.

While majorities of Democrats (69%), independents (64%), and Republicans (56%) agree that immigrants coming to this country today mostly take jobs Americans don’t want, there is less agreement on whether illegal immigrants hurt the economy by driving down wages. Two-thirds (67%) of Republicans and a majority (55%) of independents agree that illegal immigrants mostly hurt the economy by driving down wages for many Americans, while Democrats are more divided. Nearly half (49%) of Democrats agree that illegal immigrants hurt the economy by driving down wages, while more than 4-in-10 (43%) disagree, saying that illegal immigrants help the economy by providing low-cost labor.

Nearly 8-in-10 (79%) Hispanic Americans and approximately 6-in-10 white (62%) and black (59%) Americans agree that immigrants coming to the country today mostly take jobs Americans don’t want. However, there are significant levels of disagreement on whether illegal immigrants help or hurt the economy. Six-in-ten white (60%) and black (60%) Americans agree that illegal immigrants hurt the economy by driving down wages for many Americans, while nearly as many (59%) Hispanic Americans disagree, saying that illegal immigrants help the economy by providing low-cost labor.

There are sizeable class divisions on immigrants’ impact on jobs and the economy. Although majorities of white working-class (52%) and white college-educated Americans (75%) agree that immigrants coming to the U.S. today mostly take jobs Americans don’t want, a sizeable minority (39%) of white working-class Americans disagree, saying that immigrants mostly take jobs away from American citizens. Similarly, while more than 7-in-10 (71%) white working-class Americans agree that illegal immigrants mostly hurt the economy by driving down wages, only 42% of white college-educated Americans agree. Half (50%) of white college-educated Americans say illegal immigrants help the economy by providing low-cost labor.

Some of the largest divisions in views about the impact of illegal immigrants are between first-generation and third-generation Americans. Nearly 8-in-10 first-generation (78%) Americans agree that immigrants coming to the U.S. today mostly take jobs Americans don’t want, compared to 61% of third-generation Americans. Meanwhile, nearly 6-in-10 (58%) first-generation Americans also believe that illegal immigrants mostly help the economy by providing low-cost labor, while 61% of third-generation Americans say illegal immigrants hurt the economy by driving down wages.

V. Immigration Reform Policy and Values

Perceptions of the Immigration Process

Knowledge of Deportation Rates

Overall, most Americans are not aware of changes in deportation rates over the past few years. Although deportations have increased since the beginning of the Obama administration, a plurality (42%) of Americans believe that the number of illegal immigrants who were deported back to their home countries has stayed the same over the past five or six years, while nearly 1-in-5 (18%) say deportations have decreased, and less than 3-in-10 (28%) correctly state that they have increased.(10)

Democrats (32%) and independents (29%) are more likely than Republicans (21%) to correctly report that the number of deportations has increased over the past five or six years. By contrast, Republicans (25%) are nearly twice as likely as Democrats (13%) to report that the number of immigrants who were deported back to their home countries has decreased over the past five or six years.

One of the most substantial knowledge gaps on this question is between different racial and ethnic groups. Close to half (46%) of Hispanic Americans correctly report that the number of illegal immigrants who were deported back to their home countries has increased over the past five or six years, compared to 34% of Asian Americans, 31% of black Americans, and less than one-quarter (24%) of white Americans.

First-generation Americans are also more likely than second-generation or third-generation Americans to correctly identify deportation trends. Nearly half (47%) of first-generation Americans report that the number of illegal immigrants who were deported back to their home countries has increased over the past five or six years, compared to more than one-third (35%) of second-generation Americans and one-quarter (25%) of third-generation Americans.

Condition of the Immigration System

On the whole, most Americans believe the immigration system in the United States is broken. Less than 1-in-10 (7%) Americans believe that the immigration system is generally working, while 29% say it is working but with some major problems. Four-in-ten (40%) Americans report that the current immigration system is broken but working in some areas, while 23% say it is completely broken.

Public opinion on this question has remained relatively stable since 2010, when 7% reported that the immigration system was generally working, about one-third (34%) reported that it was working but with some major problems, roughly one-third (35%) Americans reported that it was broken but working in some areas, and more than 1-in- 5 (21%) said it was completely broken.(11)

There are modest partisan differences in views of the immigration system. More than 7-in-10 Republicans (73%) say that the immigration system is mostly or completely broken, compared to 62% of independents and 57% of Democrats.

There are sizeable racial gaps, with Asian Americans standing out as one of the few groups expressing more optimistic views about the functionality of the immigration system. Nearly 6-in-10 (59%) Asians Americans say the immigration system is either generally working or working with some major problems, compared to approximately 4-in-10 Hispanic Americans (41%) and black Americans (38%), and one-third (33%) of white Americans. Majorities of white (65%), black (61%), and Hispanic (57%) Americans say the immigration system is either mostly or completely broken.

Immigration Reform Policy

A Path to Citizenship for Illegal Immigrants

There is a general consensus among Americans that the immigration system should include an earned path to citizenship for immigrants who are currently living in the U.S. illegally, while few Americans favor an approach that focuses exclusively on deportation.

When asked a binary question, Americans are substantially more likely to say that the best way to solve the country’s illegal immigration problem is to both secure our borders and provide an earned path to citizenship for illegal immigrants already in the country (68%) than they are to say that the best way to solve this problem is to secure our borders and arrest and deport all those who are here illegally (29%). Support for an earned path to citizenship has increased by six points since 2011, when Americans were also more likely to prefer the comprehensive approach (62%) over the enforcement-only approach (36%).(12)

Americans also strongly support a path to citizenship when asked a three-part question that includes an option for permanent legal residency. More than 6-in-10 (63%) Americans agree that the immigration system should deal with immigrants who are currently living in the U.S. illegally by allowing them a way to become citizens provided they meet certain requirements. Less than 1-in-5 (14%) say they should be permitted to become permanent legal residents, but not citizens, and approximately 1-in-5 (21%) say they should be identified and deported.

Although majorities of all partisan groups favor an earned path to citizenship for immigrants currently living in the U.S. illegally, there are significant variations in intensity. More than 7-in-10 (71%) Democrats, 64% of independents, and a majority (53%) of Republicans favor an earned path to citizenship. Similar numbers of Democrats (13%), independents (14%), and Republicans (13%) favor a path to legal residency, but not citizenship. Nearly one-third (32%) of Republicans, more than 1-in-5 (21%) independents, and approximately 1-in-10 (13%) Democrats favor deportation.

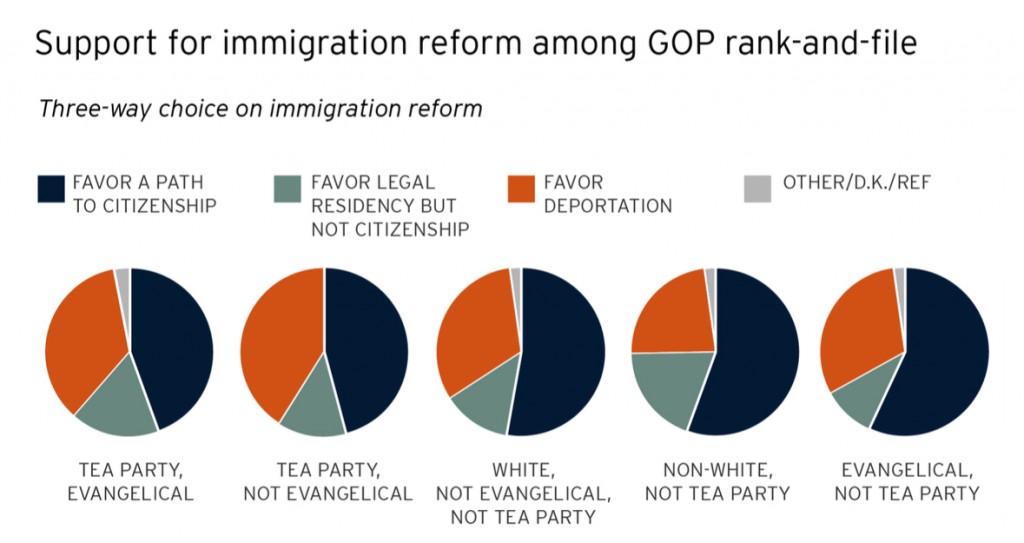

There are significant differences between two important constituencies that tend to support the Republican Party: white evangelical Protestants and Americans who identify with the Tea Party. A majority (56%) of white evangelical Protestants support a path to citizenship for immigrants living in the U.S. illegally, compared to less than half (45%) of Tea Party members. A majority of Americans who identify with the Tea Party say that immigrants in the U.S. illegally should be allowed to apply only for permanent residency status and not citizenship (16%) or be deported (36%). Nearly 6-in-10 (59%) white evangelical Protestants who do not identify with the Tea Party support a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants, compared to 41% of white evangelicals Protestants who also identify with the Tea Party (sometimes referred to as “Teavangelicals” [Brody 2012]), and 47% of Tea Party members who do not identify as evangelical.

Majorities of all religious groups, including Hispanic Catholics (74%), Hispanic Protestants (71%), black Protestants (70%), Jewish Americans (67%), Mormons (63%), white Catholics (62%), white mainline Protestants (61%), and white evangelical Protestants (56%) agree that the immigration system should allow immigrants currently living in the U.S. illegally to become citizens provided they meet certain requirements.

With the exception of Asian Americans, solid majorities of all racial and ethnic groups favor allowing immigrants currently living in the U.S. illegally to become citizens provided they meet certain requirements, although there are some notable variations. Approximately 7-in-10 Hispanic (71%) and black (68%) Americans favor an earned path to citizenship, as do more than 6-in-10 (61%) white Americans. By contrast, half (50%) of Asian Americans favor a path to citizenship. Asian Americans are, however, more than twice as likely to favor allowing illegal immigrants to become permanent legal residents but not citizens (32%), as they are to believe that they should be identified and deported (15%). Meanwhile, white Americans are twice as likely to favor deportation for illegal immigrants (25%) as they are to favor legal residency only (12%).

Deportation and “Self-Deportation”

Most Americans remain opposed to an immigration strategy that focuses exclusively on deportation, although support for this option is higher than when paired with alternatives. A majority (55%) of Americans disagree that we should make a serious effort to deport all illegal immigrants back to their home countries, while approximately 4-in-10 (43%) agree with this policy. Public opinion on this question is essentially unchanged since 2010, when 56% opposed a deportation-only approach and 42% were in favor.(13)

Even fewer Americans favor a policy colloquially known as “self-deportation,” in which conditions are made so difficult for illegal immigrants that they return to their home country on their own. More than one-third (34%) of Americans agree that this is the best way to solve the country’s illegal immigration problem, while nearly two-thirds (64%) disagree.

All partisan groups oppose a strategy of self-deportation as the best solution to the Source: Public Religion Research Institute, Religion, Values, and Immigration Reform Survey, March 2013 (N=4,465). country’s illegal immigration problem, although there are varying levels of opposition. More than 7-in-10 (72%) Democrats and nearly two-thirds (65%) of independents oppose a self-deportation approach to immigration. A majority (53%) of Republicans are also opposed, although 45% are in favor of such a proposal. By contrast, a majority (56%) of Americans who identify with the Tea Party agree that the best way to solve the country’s illegal immigration problem is to make conditions so difficult for illegal immigrants that they return to their home country on their own.

There are also significant generational divisions among both Democrats and Republicans. Among Republicans, a majority (52%) of seniors (age 65 and older) agree that a self-deportation strategy is the best solution to the country’s illegal immigration problem, compared to roughly 4-in-10 (39%) Millennial Republicans (age 18-29. More than one-third (34%) of senior Democrats favor a self-deportation strategy, compared to 19% of Millennial Democrats.

The DREAM Act

More than 6-in-10 (61%) Americans favor allowing illegal immigrants brought to the U.S. as children to gain legal resident status if they join the military or go to college, a policy which comprises the basic elements of the DREAM Act. Approximately one-third (34%) of Americans are opposed to this policy. Perspectives on this issue have not changed substantially since 2011, when nearly 6-in-10 (57%) Americans favored the basic tenets of the DREAM Act and 4-in-10 (40%) were opposed.(14)

More than 7-in-10 (72%) Democrats and 6-in-10 (60%) independents favor the basic tenets of the DREAM Act. Republicans are evenly divided, with 48% in favor of the basic elements of the DREAM Act, and 48% opposed.

With the exception of white evangelical Protestants, all religious groups, including 83% of Hispanic Catholics, 78% of Mormons, 71% of Jewish Americans, 68% of Hispanic Protestants, 64% of black Protestants, 58% of white mainline Protestants, and 55% of white Catholics, favor the basic tenets of the DREAM Act. White evangelical Protestants are divided, with 47% in favor of the basic tenets of the DREAM Act, and 48% opposed.

Majorities of all racial and ethnic groups favor allowing illegal immigrants brought to the U.S. as children to gain legal resident status if they join the military or go to college, but there are some variations in intensity. Approximately three-quarters of Hispanic (77%) and Asian (74%) Americans favor the basic tenets of the DREAM Act, compared to 64% of black Americans and 58% of white Americans.

First-generation (79%) and second-generation (77%) Americans are substantially more likely than third-generation Americans (58%) to favor the basic tenets of the DREAM Act.

Other Immigration Policies

Americans exhibit strong support for several policies that have been debated as part of a larger package of immigration reform legislation. More than 8-in-10 (81%) Americans favor creating a database that would allow employers to verify the immigration status of new hires, three-quarters (75%) of Americans favor allowing immigrants who get degrees from U.S. colleges or universities in math, science, or technology to work legally in the U.S., and 72% of Americans favor expanding “guest worker” programs that would give a temporary visa to non-citizens who want to work legally in the U.S. There is strong support for these policies across various subgroups.

Preferences for Different Groups of Immigrants

There is a general consensus that immigrants with family members living in the U.S. legally, as well as immigrants who attended an American college or university, should be given preference by the immigration system, even if it means others may have to wait longer. Approximately 6-in-10 Americans agree that immigrants seeking legal status who have a spouse currently living in the U.S. legally (63%), have children or parents currently living in the U.S. legally (60%), or have a degree from an American college or university (59%) should be given preference by the immigration system, even if it means less space for others. Americans are nearly evenly divided on whether immigrants who can speak English fluently should be given preference by the immigration system (48% agree, 47% disagree).

Notably, Americans are less willing to give preference to two groups. More than 6-in-10 (63%) Americans disagree that preference should be given to immigrants who have a gay or lesbian spouse currently living in the U.S. legally. Two-thirds (67%) of Americans also disagree that preference should be given to immigrants who are from Western Europe.

Overall, Democrats are more supportive than Republicans of giving preference to certain types of immigrants. More than two-thirds (68%) of Democrats and nearly 6-in-10 (59%) independents agree that immigrants who have children or parents currently living in the U.S. legally should be given preference by the immigration system, compared to less than half (49%) of Republicans. Democrats (67%) are also more likely than Republicans (52%) to agree that immigrants who have a degree from an American college or university should be given preference, while independents (58%) fall in between.

There is a significant generational divide in whether preference should be granted for immigrants with gay spouses. Nearly half (46%) of Millennials say that immigrants with a gay or lesbian spouse currently living in the U.S. legally should be given preference, compared to only 21% of seniors.

Values Guiding Immigration Reform Policy

Just as there is general agreement about immigration policy, especially support for a path to citizenship, there is also a broad consensus about a set of values that should guide immigration policy. Five values are rated very or extremely important as moral guides to immigration reform by approximately 8-in-10 Americans: promoting national security (84%), keeping families together (84%), protecting the dignity of every person (82%), ensuring fairness to taxpayers (77%), and enforcing the rule of law (77%). Nearly 7-in-10 (69%) also say following the Golden Rule—“providing immigrants the same opportunity that I would want if my family were immigrating to the U.S.”—is a very or extremely important value. Fewer Americans say continuing America’s heritage as a nation of immigrants (52%) or following the biblical example of welcoming the stranger (50%) are very or extremely important guides for immigration reform.

Since 2010, levels of support for each of these values have remained relatively steady, with one exception.(15) The percentage of Americans saying that ensuring fairness to taxpayers was an extremely or very important value fell 7 points from 2010 (84%) to 2013 (77%).(16) This decrease was due primarily to a nine-point drop in support for this value among Democrats (from 82% in 2010 to 73% in 2013).

Generally speaking, there is much agreement across party lines, with partisan differences amounting mostly to contrasting emphases rather than wholesale disagreements. The largest difference between Democrats and Republicans, for example, is 13 percentage points.

These differences cluster into two areas: pragmatic-legal vs. cultural-religious values. Republicans rank the pragmatic-legal values of promoting national security, enforcing the rule of law, and ensuring fairness to taxpayers consistently higher than Democrats by double-digit margins. The largest pragmatic-legal values gaps occur on the values of promoting national security (Republicans 94%, Democrats 81%) and enforcing the rule of law (Republicans 86%, Democrats 73%), where Republicans rate each of these values 13 points higher than Democrats. Democrats, by contrast, rate many of the cultural-religious values higher than Republicans. The largest cultural-religious values gaps occur on the values of following the Golden Rule (Democrats 75%, Republicans 62%) and continuing America’s heritage as a nation of immigrants (Democrats 59%, Republicans 47%). Democrats rate these values 13 points and 12 points higher respectively than Republicans.

Religious groups across the spectrum largely agree on a set of values that should guide approaches to immigration reform. For instance, white evangelicals are just as likely as white mainline Protestants, Catholics, and religiously unaffiliated Americans to say protecting the dignity of every person or keeping families together is very or extremely important. However, white evangelical Protestants and black Protestants are significantly more likely to say that the biblical value of welcoming the stranger is an important moral guide (65% each), compared to white mainline Protestants (41%) or religiously unaffiliated Americans (31%). Despite the strength of this value among white evangelical and black Protestants—groups that share an evangelical theological orientation and devotion to the Bible—the biblical value of welcoming the stranger still ranks comparatively lower than most other values among these groups.

The value of continuing America’s heritage as a nation of immigrants has much stronger appeal among Americans with a closer personal connection to the historical centers of previous waves of immigration, such as Americans living in the Northeast, older Americans, and Catholics. More than 6-in-10 (62%) Americans living in the Northeast, including 65% of New Yorkers, say this value is extremely or very important, compared to only half (50%) of Americans in the South and Midwest. Seniors are significantly more likely than Millennials to say this value is extremely or very important (58% vs. 45%). There is also a significant religious divide between white Catholics, a group connected with high levels of immigration in the early twentieth century, and white Protestants, groups that typically have much older immigration histories. Nearly 6-in-10 (57%) white Catholics say that continuing America’s heritage as a nation of immigrants is extremely or very important, compared to less than half of white evangelical Protestants (49%) and white mainline Protestants (49%).

These values are correlated with views on immigration policy in different ways. Agreement with three values—continuing our heritage as a nation of immigrants, following the Golden Rule, and protecting the dignity of every person—predicts higher support for a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants. Agreement with two values—ensuring fairness to taxpayers and enforcing the rule of law—predicts lower support for a path to citizenship.(17) For example, there is a 30-point gap in support for a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants between those who say two different kinds of “rules” are important as moral guides for immigration reform. Among those who say that following the Golden Rule is extremely important, 78% say immigrants who are currently living in the U.S. illegally should be allowed to become citizens provided they meet certain conditions, compared to only 48% of those who say enforcing the rule of law is extremely important.

Notably, the values of promoting national security, following the biblical example of welcoming the stranger, and keeping families together are not independent predictors of support for a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants currently living in the U.S.

The Influence of Knowledge and Perceptions of Social Change on Support for a Path to Citizenship

In addition to values, knowledge of the numbers of deportations over the past few years and perceptions of how American culture and communities are changing are strongly correlated with a key part of immigration reform: support for a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants who are already in the U.S.

Among those who correctly believe that the number of illegal immigrants who have been deported back to their home countries has increased over the last five or six years, 7-in-10 (70%) support a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants, 15% say they should be given permanent legal status but not citizenship, and 13% say they should be deported. By contrast, among those who incorrectly believe the number of deportations has decreased over this period, less than half (49%) support a path to citizenship, 13% support permanent legal status but not citizenship, and more than one-third (35%) say illegal immigrants should be deported. However, knowledge about deportations is at least partially conditioned by political orientation. Self-identified liberals are significantly more likely than conservatives to say deportation has increased (36% vs. 24%), while conservatives are twice as likely as liberals to say it has decreased (24% vs. 12%).

Perceptions of whether American culture and way of life has changed for the better or the worse since the 1950s also influence support for a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants. Among those who say American culture has changed for the better since the 1950s, nearly three-quarters (73%) support a path to citizenship, 14% support permanent legal status but not citizenship, and 12% say illegal immigrants should be deported.

Among those who say American culture has changed for the worse, a majority (56%) support a path to citizenship, 13% support permanent legal status, and nearly 3-in-10 (28%) say they should be deported. Among the nearly one-third (32%) of Americans who believe that immigrants today are changing their communities a lot, less than half (47%) support a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants, 16% support permanent legal resident status but not citizenship, and more than one-third (34%) say they should be deported. These views are sharply different from Americans who say immigrants are changing their communities a little. Among this group, nearly two-thirds (64%) support a path to citizenship, 19% support permanent legal resident status, and 15% say illegal immigrants should be deported.

VI. Political Change, Cultural Change, and Immigration Reform’s Opportunity

Perspectives on Survey Findings By E. J. Dionne Jr. and William A. Galston

There is a surprising level of hope among Democrats and Republicans negotiating comprehensive immigration reform legislation. An issue that has been deeply divisive and has long resisted a legislative solution finally seems ripe for action. It is widely said that Republicans, having seen their presidential share of the Hispanic vote drop to a disastrous 27%, are prepared to take steps they were unwilling to consider before the 2012 election.

But this view has been expressed largely at elite levels of the Republican Party. When it comes to legislation, the chances for action seem greater in the Senate than in the House of Representatives. A large share of the Republican majority in the House represents strongly conservative districts where GOP margins are so high that a member’s greatest fear is a primary from the right, not a general election challenge. This essay examines whether changes in the Republican view extend beyond the party’s elite. It also looks at cultural factors affecting views on immigration, in particular the attitudes of the white working class, and also whether there is a politics of nostalgia that looks back to the 1950s as a particularly blessed time for the nation.

One of the most striking overall findings of the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) survey is that the opening politicians see on immigration reflects something more than opinion at the top of the political system. Rank-and-file Americans also seem prepared to support broad immigration reform that includes a path to citizenship. This view is held by a majority of Republicans. One of the survey’s most striking findings is that the halfway position of providing illegal immigrants with a path to legal status but not citizenship – a position held by many Republican political leaders – is the least popular option among rank-and-file Republicans.

When Republicans are given a choice of legalization with a path to citizenship, legalization in the form of permanent legal resident status without a path to citizenship, and deportation, 53% favor a path to citizenship, only 13% favor legalization without citizenship, and 32% favor deportation. Among Democrats, 71% favor a path to citizenship, while the legalization-without-citizenship and the deportation options receive just 13% each. Independents fall slightly closer to the Democrats, with 64% supporting a path to citizenship, 14% favoring legalization without citizenship, and 21% favoring deportation. As is often the case, the views of the country as a whole are nearly identical to those of independents.

There is a consensus for action on immigration, and it crosses partisan lines.

It’s certainly true that there remain strong feelings inside the GOP against illegal immigration. Majorities of Republicans in the Midwest and the South agree that newcomers are threatening to the United States, and 65% of both groups agree that we should make a serious effort to deport all illegal immigrants back to their home countries. Tea Party members are also more skeptical of immigration reform than are other Republicans.

All this points to what may be the largest challenge to immigration reform efforts: Republicans face a problem of coalition management that Democrats do not confront. Republicans are sharply divided by the issue; Democrats are not.

Still, even a plurality of Tea Party Republicans favors a path to citizenship. Importantly for GOP members of Congress from strongly Republican parts of the country, a majority of Republicans in the red states — 56% — favor reform with a path to citizenship.

What explains support among Republicans for immigration reform? This survey is not the first to find considerable support for immigration reform that includes a path to citizenship. But it does underscore the extent to which Mitt Romney’s poor showing among Hispanic Americans because of his stance on immigration is a political fact affecting the views of the Republican rank-and-file as well as the attitudes of the party’s political consultant class. Asked if the Republican Party’s stance on immigration hurt it or helped in recent elections, 39% of Republicans say the party was hurt and only 11% say it was helped by its position on immigration. (The rest say it made no difference or are unsure.) This view is held by Republicans across regions, though it is held slightly more strongly by Republicans in the Northeast and in the West. A concern for the party’s long-term well-being may well be driving a shift in Republican attitudes on immigration all the way down to its grass roots.

Surveys of opinion are imperfect guides to future legislative maneuvering. But the PRRI survey suggests that an immigration bill providing for legalization without a path to citizenship may be the least promising option politically. The Republican Party’s most vociferous opponents of immigration reform are against it altogether and prefer a deportation strategy; it is not clear that they would be appeased by a halfway solution. And when given a straight binary choice between deportation and a path to citizenship, Republicans favor a path to citizenship by a 56% to 41% margin; support for citizenship rises to 58% among Republicans in the Northeast and 60% among Republicans in the West. At the same time, the legalization-without-citizenship approach would not likely help the party to broaden its political appeal. It is rejected by both Democrats and independents, and is strongly rejected by Hispanic Americans, 71% of whom favor a path to citizenship.

Underscoring the fact that Republicans are not as punitive in their approach to illegal immigrants as conventional analysis often suggests, the survey finds that Romney’s “self-deportation” proposal – making illegal immigrants’ situations so difficult that they would leave the country voluntarily – is actually opposed by most Republicans: only 45% support it; 53% oppose it.

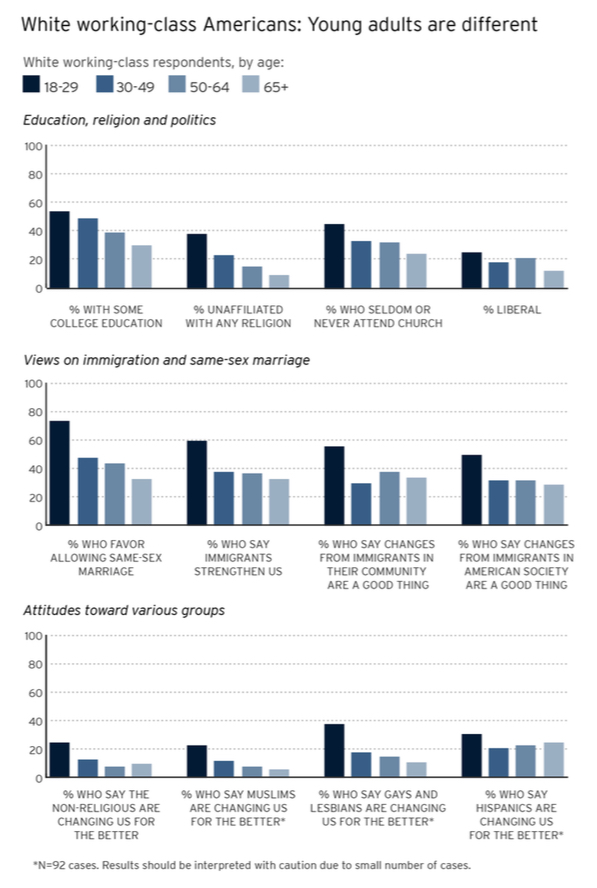

Not only do Republicans in Congress appear to have room to support comprehensive immigration reform; many in their rank-and-file seem to welcome this possibility. And this view extends to white working-class Americans who have grave concerns about illegal immigration and worry that immigrants are driving down wages. Nonetheless, white working-class Americans also reject a purely punitive approach to the problems created by a broken immigration system.

The White Working Class

Since the end of the 1960s, the shifting sentiments and allegiances of the white working class have shaped the contours of American politics. Once at the heart of the New Deal coalition, the rise of racial politics and the counterculture sent many members of this demographic group on a quest for alternatives to post-New Liberalism. Over the past three decades, white working-class Americans have supported many Republican and conservative candidates, a trend that has intensified in recent years.