About the Project

In partnership with E Pluribus Unum (EPU), PRRI convened a series of 26 focus groups across 13 southern states to discuss how residents think about public spaces in their communities and about the legacy and future of Confederate monuments.[1] As documented in the Southern Poverty Law Center’s “Whose Heritage?”project, as of 2022, more than 2,000 Confederate monuments and memorials still exist around the country. Most are concentrated in former Confederate states, but many others have been erected across the country. These monuments take the form of statues and memorials, as well as the names of schools, streets, government buildings, and public parks. Many were built in the early 20th century, as a tribute to the “Lost Cause” of the Confederacy, and some were even dedicated in the 21st century.

The past 10 years have brought waves of protests calling for racial justice, triggered by events such as the mass shooting of Black parishioners by a white supremacist at Mother Emanuel Church in Charleston, South Carolina; the “Unite the Right” white-supremacist march in Charlottesville, Virginia; and the killing of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis, Minnesota. These protests have sparked discussions about the nation’s racial history, during which some people have called for the removal of public monuments and memorials that honor the Confederacy and its leaders. Meanwhile, other people have responded by strongly objecting to their removal.

To understand Black and white Americans’ views on this topic, PRRI and EPU convened two focus groups in each of the 13 included states, with participants divided by race: one white group, with a white moderator, and one Black group, with a Black moderator. Having all-white and all-Black groups created a space in which participants were less likely to self-censor their views for fear of offending participants of a different race.

Since part of the purpose of the project was to investigate the role of religion in conversations about race and public spaces, the groups included only those who affiliated with a religion and said it was important in their life. Participants were selected to balance other characteristics within the group, including age, gender, and partisan affiliation.[2] Recruitment for each group was focused on a specific city within each state, but owing to the other criteria, some participants came from outlying areas near the city or even other parts of the state.[3]

As part of the project, PRRI and EPU also fielded a national survey, with oversamples in each of the 13 focus group states, to see how the focus groups resonated with larger representative samples. Results from the survey are provided throughout this report to provide additional context for the focus group findings.[4]

These focus groups provided an important environment for conversations about public spaces and the legacy and future of Confederate memorials. Many Black Americans shared deeply personal anecdotes about how the legacy of the Confederacy has touched their lives and how memorials serve as reminders of a violent past and a tense present. Furthermore, these focus groups shed light on the work that still needs to be done to bridge racial divides in American communities, particularly regarding Confederate memorials.

Memorializing Public Spaces in Action

In addition to hosting the focus groups, EPU also conducted interviews with leaders and members of seven organizations and grassroots groups doing work around memorialization in public spaces. The interviews were aimed at gaining insight into these people’s motivations and approaches to the work, as well as the impact the groups hope to have on their communities. These organizations are grappling with the challenges related to public memorials in different ways. Some are focused on the removal of Confederate monuments and artifacts. Others are looking to install new memorials in remembrance of victims of lynching and other extrajudicial racial violence. Still others are focused on using existing systems of memorialization and preservation to tell stories that have traditionally been left out of mainstream historical accounts. The following seven organizations are highlighted throughout this report:

- The Ida B. Robinson Institute in Richmond, VA

- The Committee for Justice, Equality, and Fairness (CJEF) in Walton County, FL

- The 2022 Day of Repentance in Richmond, VA

- St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, VA

- The Orleans Legacy Project in New Orleans, LA

- The Wesleyan College Lane Center for Social and Racial Justice in Macon, GA

- The Lafayette County Remembrance Project (LCRP) in Oxford, MS

Qualities of Ideal Public Spaces

The Good and the Bad of Existing Public Spaces

To start the groups off with a comfortable topic, participants were asked to list and discuss public spaces in their communities. Most of them listed parks and nature preserves, walking paths and hiking trails, splash pads and playgrounds, concert and event venues, downtown areas, and green spaces.

Nearly all group participants — both Black and white — expressed a desire for high-quality public spaces that are clean, well-maintained, and have areas that are welcoming to children and families. Most participants expressed a desire for parks and outdoor spaces, while some wanted greater access to libraries and other community facilities, such as recreation centers. These results echo those from the 2022 PRRI-EPU Religion and Inclusive Public Spaces national survey, in which nearly all Americans (96%) agreed with the statement “Public spaces in our community, like parks, libraries, government buildings, and public university campuses, should be open and welcoming to people of all races and backgrounds.” Those in agreement included 97% of white Americans and 89% of Black Americans.

Many participants, both Black and white, cited crime and violence as reasons they might avoid public spaces in their community. While the issue of crime was not necessarily a deterrent to using most public spaces, many participants gave examples of shootings at sporting events, muggings or car break-ins, and other petty crimes that had happened in public spaces in their community. Some participants mentioned homeless people or homeless encampments as reasons they might avoid public spaces. Several participants said that crowding and increasing crime in some spaces made them feel unsafe.

“The main thing that they need to work on is the crime. But I guess because of what’s happened with the pandemic, all cities are having issues with crime. So that’s one of the things.… They had a crawfish festival, so I went to the crawfish festival that Friday. That Saturday, they had a shooting at the crawfish festival.”

Black woman, Mississippi

“I used to like to go to Centennial Park because of the museum and just the green space. It’s really pretty there, but the homeless population is just so bad here that it’s just not a safe place to go sometimes. Nothing against the homeless people, I know they can’t help the position they’re in, but it would be nice if the government could do something to help them.”

White man, Tennessee

However, the groups had diverging opinions on what constitutes safety in a public space. Some participants in the Black groups said they would take an increased police presence as a sign that they might not be welcome in a certain space, or that they would assume the police were there to ensure that only certain types of people were welcome (i.e. middle class or affluent white people). However, this view was not universal, and some Black participants noted that they felt better able to use public spaces if they felt more secure in those areas.

“When I see a lot of police somewhere, I genuinely don’t want to go there.”

Black woman, Louisiana

“I love the outdoor spaces and some of them have pretty decent restaurants, but I also want to see good security … because a lot of times you hear about burglaries at some of the public spaces.”

Black woman, Arkansas

“One thing I look at is the security and the surrounding area. If it’s barely lit or you know, just looks like something could happen to you … I usually won’t go.”

Black woman, Louisiana

In cities that have seen a rapid influx of new residents, participants in both Black and white focus groups commented on the resulting changes. Black participants, in particular, noted that their desires seem to go unheeded by local officials or that the cities they live in are more interested in attracting new residents than delivering improvements for existing residents.

“It’s very disturbing the amount of buildings that have been torn down to replace new ones. Beautiful homes, on nice lots, that get big, tall, skinny crammed on them … so that’s kind of disappointing.”

White woman, Tennessee

“I have always wanted to see a more urban place downtown on the river, like an old blues, jazz, gospel kind of thing. They have all the other stuff downtown, but they don’t have anything that’s more Black.”

Black woman, Tennessee

Memorialization in Public Spaces

Nearly all participants felt that it was acceptable to use public spaces to memorialize individual people, and both Black and white participants said people who had a direct, positive effect on their community should be memorialized. Additionally, many participants were opposed to the idea that wealthy or powerful figures should be able to simply buy their way into being memorialized in public spaces.

“It would be cool, like, if someone from that area had done something, like, to name something in their whole area about them. I would feel more like excited [if] it was somebody from the area or somebody who did something specifically for our area was memorialized in some kind of way.”

Black man, Alabama

“I would say what they stood for, what they did while they were alive, or just the work. For an example, we have an elementary school, Mary C. Snow, and they named the school after her, like built the elementary and everything for her work in what she did in the Charleston area.”

Black woman, West Virginia

“Any time I think about a statue, it’s something that not just happened a long time ago and you’re like still seeing the change, but is like they did something for a large amount of time, and it has impacted their community now and is still impacting the communities in front of them and so on. So, I feel like that’s something that doesn’t impact, that goes beyond just the maybe couple years that they’re working in.”

White woman, Alabama

“I don’t believe they should make a statue or something for somebody just because they’ve got a lot of money.”

White man, Mississippi

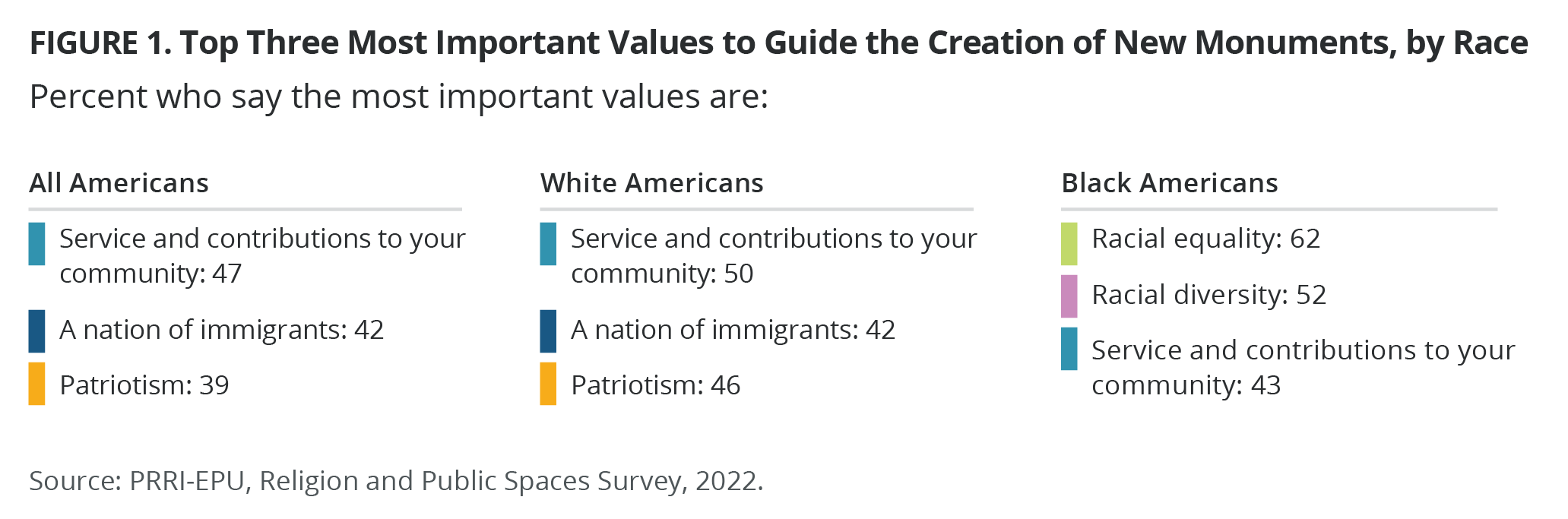

These views are in line with results of the national survey, which asked Americans to select three values, out of a list of 12, that they believe would be the most important in guiding the creation of new monuments and art in public spaces. The top three values selected were service and contributions to the community (47%, including 50% of white Americans and 43% of Black Americans), the idea of a nation of immigrants (42%, including 42% of white Americans and 29% of Black Americans), and patriotism (39%, including 46% of white Americans, but just 14% of Black Americans).

Many white participants spoke only in broad terms of what might disqualify someone for public memorialization. For instance, for many participants, lawbreakers and offensive or controversial figures came to mind as people who should be disqualified, but more specific details were sparse. One white participant mentioned that George Floyd was inappropriate for a memorial because he had broken the law.

“If it’s something heinous like Jeffrey Epstein, people going to this island and memorializing and thinking that’s a great place — that’s in poor form. I know when Black Lives Matter became the hot topic in 2021, everyone here was saying our neighborhoods should be renamed, because we have a lot of things like Wexford Plantation, Wellingrove Plantation, all of these lovely homesites, neighborhoods that have the word ‘plantation’ on them. But ‘plantation’ was just a large plot of land where maybe indigo or cotton or whatever used to be grown at the time. It’s not saying that these places still are enslaving people. So that became such a painful hot topic.”

White woman, South Carolina

“I’m sorry if this upsets anybody, but I think George Floyd [should not be memorialized]. That’s not somebody to be commemorated. And I don’t mean any ill will towards him or his family, but when you have a history of substance abuse and rape charges, et cetera, those are people that I feel it’s a double-edge sword. On one edge, it’s assuming, because I don’t know, because I don’t believe in it, but I’m assuming people want a statue because — I don’t really know why. Just because … I assume people want him because of the way that he was killed. But I think, sadly, on the other end, you want those people to be people that you would be … It also glorifies the other part of the life. Does that make sense?”

White woman, Alabama

Participants in many of the Black groups brought up Confederate memorials in this discussion, anticipating the topic before the moderator introduced it. The majority of them said that Confederate leaders and slave owners do not deserve to be memorialized. In fact, the PRRI-EPU Religion and Inclusive Public Spaces national survey shows that three in four Black Americans (76%) agreed with the statement “We should not memorialize historical figures who supported the Confederacy or racial segregation in public spaces,” compared with less than half of white Americans (48%).

“I don’t believe that publicly tax-funded places should be named for any individual or entity that is used to intimidate, discriminate, marginalize, disenfranchise individuals of any race, sexual orientation, disabilities. I think if it’s public and it’s funded by tax dollars, it should be an inclusive individual.”

Black woman, Arkansas

“I mean, what did the Confederacy stand for? It stands for slavery. When you think of Confederacy, you think of the KKK, you think of all the oppression that we still to this day from the people across the aisle the GOP. So those are things — as a matter of fact, there’s a park in Macon, I can’t remember the name of it, I have a great aunt who lived down here who passed a couple years ago, when she was a kid, black people couldn’t walk through the park.”

Black man, Georgia

“If someone is found to be a racist.”

“Yeah, if you come with a racist group, that kinda cancels out whatever you did.”

“Because that means you didn’t want it for everybody, you only wanted it for a particular group of people.”

Exchange between three Black men in Virginia

IDA B. ROBINSON INSTITUTE

BLACKWELL COMMUNITY OF RICHMOND, VA

“That’s our expectation, that we will do that kind of work to bring … an unstoppable hope.”

Bishop Ernest Moore, The Ida B. Robison Institute

The Ida B. Robinson Institute is a grassroots organization whose mission is to engage faith and community leaders in the continued uplifting and passing down of the stories and legacies of important Black individuals in Richmond’s history. Among other initiatives, the Institute aims to use historical markers, historical designations, and new street names as key elements of its effort to publicly recognize Black history that has not been formally acknowledged in Richmond.

The Legacy Project: A Call to Continue is an initiative of the Institute that focuses on the public memorialization of Black historical figures who have shaped the Richmond landscape. Bishop Annie B. Chamblin and James H. Blackwell are the first two individuals whose stories the project will memorialize.

Bishop Annie B. Chamblin served as a pastor of the Jerusalem Holy Church in Richmond’s Blackwell neighborhood from 1938 to 1977. Having been limited to receiving a third-grade education, Chamblin was a strong proponent of formal education and sought ways to increase education opportunities for Blackwell residents. She established a library in the church, which hosted after-school study hours and supported parishioners in pursuing post-secondary degrees and other training programs. A passionate civil rights activist, the Bishop started and led many initiatives that shaped the culture of the community and responded to the needs of the time. The Institute is working to establish a historic marker on the lawn of the church where she pastored, which is still standing, and to get a street named for her in the Blackwell community.

James H. Blackwell served as the principal of the African American High School in Manchester, Virginia, for 22 years. In 1910, Manchester was annexed into the city of Richmond, which prohibited Black community members from holding positions of authority over white residents. As a result, Blackwell was demoted from principal to teacher, and a white principal was hired in his place. Blackwell had been instrumental in the development of curricula and programming for the school and was a major figure in creating educational and employment opportunities for Black students until his death in 1931. Twenty years after his death, a housing project was named for him, and later the Manchester neighborhood was renamed Blackwell. In 2017, the community came together and successfully fought an attempt to revert the neighborhood’s name back to Manchester. The Institute is supporting community efforts to further memorialize Blackwell, for instance by having his former home designated as a historical site through the Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

As the former capital of the Confederacy, Richmond has a strong system of museums, historical markers, monuments, and tributes dedicated to that era of the city’s history. The Institute is based in the Blackwell community, on the south side of Richmond, a sector that has historically had (and continues to have) a predominantly Black and brown population. Over the decades, many of those Black and brown residents have made amazing contributions to society through the fields of education, science, business, and more. For the Institute, it is important to have memorials and markers in public spaces to tell that story.

Two Views of History

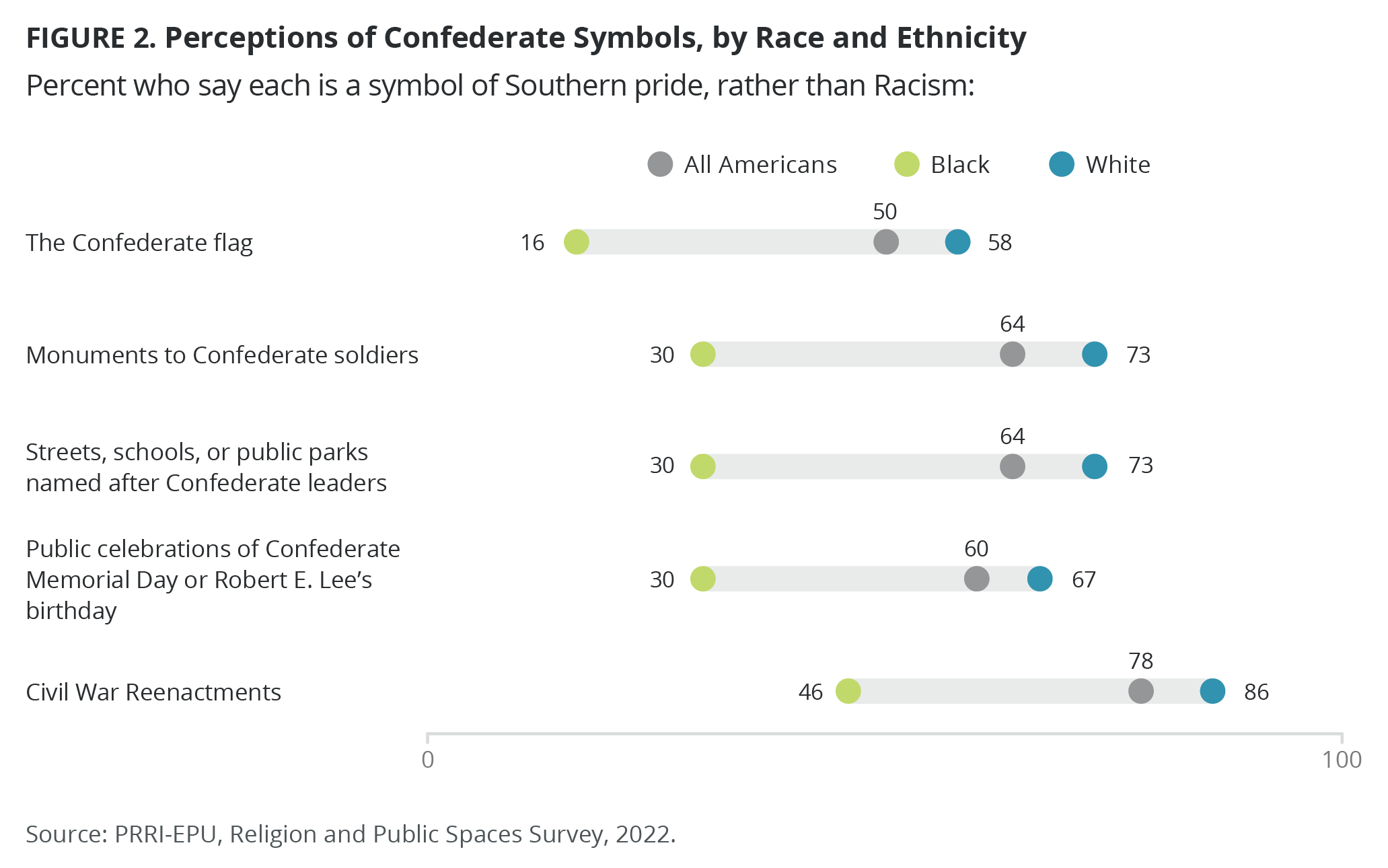

The white and Black focus groups sharply diverged when assessing the meaning of Confederate monuments and memorials and of public spaces named for Confederate leaders or slave owners. The national survey bears this out as well: when Americans were asked if monuments to Confederate soldiers were more a symbol of Southern pride or more a symbol of racism, about two-thirds (64%) said they were symbols of Southern pride, but only 30% of Black Americans agreed, compared with 73% of white Americans. By contrast, most Black Americans (63%) say that such monuments are symbols of racism, while only 25% of white Americans say the same.

In some of the most powerful moments of the focus groups, many Black participants shared blunt thoughts about Confederate memorials.

“It’s not about heritage. If it was about heritage, then the people who say ‘heritage’ would also teach what they were doing [was] wrong, like they do in Germany.”

Black man, Virginia

“It is the heritage, but what is that heritage that you’re talking about? … No other country in the world are the losers of the war honored except United States of America. I’m not from the South. I’m from New York. I was born in New York. You all lost the war. They keep telling us to get over it. Get over it.”

Black woman, South Carolina

“I was thinking just now [about] riding around as a boy in Richmond and seeing the statues of Robert E. Lee and all that, before I learned about who they were. I used to think those statues were so cool. So, I actually felt hurt behind it, I kind of felt like betrayed.… Me being a Black man, you know, thinking that stuff was cool. How’s that supposed to make me feel and look?”

Black man, Virginia

Several Black participants also discussed how they view Confederate memorials in the context of the nationwide racial justice protests in the summer of 2020, particularly in cities like Richmond, Virginia, and New Orleans, Louisiana, where prominent Confederate memorials have been removed.

“As far as the statues coming down … it was about time. They should have did this a long time ago. And the fact that they waited so long, I feel like it promoted racism here. I can’t speak about all over the United States, but here in Richmond it promoted racism. So it’s like they needed to come down. It was just a waiting process. We’ve been waiting on it.”

Black woman, Virginia

“They were traitors to this country, and they should’ve been considered as that and remain in history as traitors. Don’t celebrate their history by commemorating them with buildings, statues.… I applaud every city and state that took all those down. I applaud the State of Mississippi that took that Confederate flag apart and come up with a new one. It’s just a great thing.”

Black man, Mississippi

The monuments are not an issue of history for Black participants. Many focused on what Confederate monuments mean to them in the present. Many feel that they are indicators of unwelcomeness or remind them that they are second-class residents.

“If you were mistreating and owning slaves, what is so great about you? What did you do that was so wonderful? OK, you fought in the war, but then people were fighting for their lives on your plantation.”

“What she’s saying is basically: How can I feel supported in a state or an area if they’re making monuments that were full of racism and slave owners and practically Ku Klux Klan members? … I get exactly where she’s coming from.”

Exchange between two Black women in Kentucky

Other Black respondents extended this discussion to touch on their experiences with other Confederate iconography, such as Confederate flags. Many Black Americans in the survey indicate views similar those expressed in the focus groups: 77% of Black Americans (compared with 40% of white Americans) say the Confederate flag is more of a symbol of racism than of Southern pride.

“When I see people riding around in their big trucks with the Confederate flag blowing in your face, or when Trump was president and it was the Trump 20-whatever and then the Confederate flag. And it’s just, I felt like in a way it’s kind of like a slap in the face.… It’s meant to hurt your feelings. It’s not just there for their own big ego, let me just put it that way.”

Black woman, Tennessee

“[My daddy told me], `If you see this, this is them pretty much saying like they don’t like Black folks, so be aware of the flag.’ So that stuck with me, and when I see any of it — the flag, the Confederate statues — like, they have to go. When someone of color is doing something that’s monumental, we’re not plastering their statue in different places. Like, even at Ole Miss … the first Black guy that integrated Ole Miss, I think they have his statue out there. And I want to say during, you know, when the Black Lives Matter, all the protests and stuff, started with the killings and stuff, like around ‘19 and ‘20, they vandalized his statue.… You have literally one statue of a Black man on this campus, and you vandalize it, but you have all these Confederate statues, and you know, they’re at the parks.”

Black woman, Mississippi

The issue of Confederate monuments and memorials was much less salient to the overwhelming majority of white participants. Many white participants saw monuments and memorials as physical manifestations of a vague “history,” but very few had developed thoughts on why Confederate memorials exist in their current form, beyond the simple fact that they memorialize someone notable from the past.

“I think it’s a big mistake to remove anything that reflects a piece of history, regardless of whether it was a good thing at the time or a bad thing at the time. If you go to countries, there are centuries and centuries of monuments and architecture and sculpture that may or may not have been a good or bad thing at the time, but they’re still there. And I don’t agree with removing major things that have occurred throughout the southeast just because now people find them offensive, because you’re removing a piece of history, which is there for us to now learn from.”

White woman, South Carolina

“I mean, slavery was really common in the South. Not to say it was right — it wasn’t, by any means — but to say that anybody who owned slaves was a bad person, I mean, if you look at most of the major presidents and things, people in our country, they probably all owned slaves to some extent. So, I think looking at some of these things from … a modern lens, seems a little strange to me in a sense of, I don’t necessarily want to try to wipe away memorials and events that happened in the past.”

White man, North Carolina

“We had an incident here in Danville where there was a very large statue that was removed from a more-or-less public space. And I thought it was a shame, because that man was a man. My husband has family that fought in the Civil War on the Confederate side — none of whom owned slaves, by the way, they were all poor. But they’re people, and they fought for something they believed in, whether now we look back and think whether it’s right or wrong. So, yeah, I don’t think taking things away from history like that is correct.”

White woman, Kentucky

Most white participants seemed to lack a vocabulary for talking about race and racism, and very few white participants ever brought up the concept of race or mentioned that Confederate monuments could be offensive or hurtful specifically to Black people. Most white focus group participants spoke in vague terms about the fact that “some” might be offended or hurt by Confederate symbols but did not specifically mention Black community members specifically.

Furthermore, many white participants felt that it was impossible to balance sensitivities when determining whether someone was worthy of memorialization. When probed, many white participants felt that some people would be offended by any monument or memorial, and therefore reform was not a worthwhile effort. This aligns with survey data: 71% of Americans agree that when it comes to monuments and art in public spaces, everything will be offended by something, so there is no point in trying to please everyone. White Americans (75%) are much more likely than Black Americans (51%) to agree with this sentiment. A handful of white participants took this to an extreme, suggesting that no one should be memorialized, that streets should be given completely generic names, or that there should be no monuments or statues memorializing people.

“I guess if they did [rename streets named after Confederates], then you should have no street names with anyone’s name on it, or any nationality on it, or any religion on it. I mean, they should all be Main Street, Locust Street, Elm Street, or a numbered street — no Martin Luther King or Daisy Baker’s Drive, or Robert E. Lee Drive, or Elvis Presley Drive, or Bill Clinton Drive, none of that. Because if you’re going to appease one, you can’t take the risk of upsetting anyone.… They all have to be street trees and flowers and numbers and colors, that would be the only way that a city could be fair.”

White man, Arkansas

“I think one thing that people forget is that it was also a geopolitical war and not just a race-based war. There were people that were just enlisting into the military and went through the ranks and they were generals, so they had never owned slaves, it was never racially charged for them. And I think it gets to a point where it’s like, if we take down literally everything, we’d have to take down the pyramids in Giza, the Roman Colosseum, because they were all enslaved there.”

White woman, Kentucky

However, a few white participants did indicate discomfort with statues some view as racist, or at least empathy with that viewpoint, particularly when thinking about the history of when and why the statues were put up.

“We should not memorialize untruths.… I had mixed feelings at the beginning, because I did not want to rewrite history. But then when I learned the real history — that the only reason they were put up is that the Daughters of the Confederacy did not want anyone to think that their poor souls died for a lost cause. But they did die for a lost cause. That’s the truth. So don’t put up a memorial that’s gonna say something that’s not even true.”

White man, Louisiana

“I didn’t like when we moved here and the high school that my boys would’ve gone to was [Confederate General and Ku Klux Klan leader Nathan] Bedford Forrest. And I knew what his role in the founding of the Ku Klux Klan was. That bothered me. I always said my boys will never go to a school who’s named for that.”

White woman, Florida

Assessing the groups holistically shows that there are deep rifts between Black and white Southerners when it comes to how they view the Confederacy within the broader context of history. Many white participants see current memorials as evidence that a famous historical figure existed and did important things, while many Black participants see these monuments as warnings about the violent system that punished and enslaved their ancestors, or as reminders that they are still seen as second-class citizens across the South.

THE COMMITTEE FOR JUSTICE, EQUALITY, AND FAIRNESS

WALTON COUNTY, FL

“We no longer have ‘white only’ markings around town. We no longer have segregated schools. But that Confederate flag being there goes back to that time for me.”

Drexel Harris, Committee for Justice, Equality, and Fairness

“I want the ones that are in power to understand what it means to us when we go to that courthouse to pay our taxes, to get our tags, to vote. It’s a little sting every time that you have to pass it and endure it. It’s like a slap in your face.”

Victoria Crystal, Committee for Justice, Equality, and Fairness

The Committee for Justice, Equality, and Fairness (CJEF) is a community-based group in Walton County, Florida that is advocating for the removal and relocation of a Confederate monument and flag that currently sit on the grounds of the Walton County Courthouse in the town of DeFuniak Springs. Originally a subcommittee of the Walton County Democratic Executive Committee, CJEF evolved into an independent group in 2017. Since then, CJEF members have tirelessly attended county commission meetings, written letters, published articles, and met with city and county officials in an effort to build understanding about how having a Confederate monument on public grounds impacts many community members and to foster a discussion about the possibility of moving the memorial.

The Walton County monument has the distinction of being the first Confederate monument erected in Florida. Commissioned by a women’s association in 1871, it was originally situated on a church property and was later moved to a nearby town before being relocated to DeFuniak Springs when it became the seat of Walton County. The Confederate flag, however, was added in April 1964, as the nation and the local community were engaged in heated debate over integration and the Civil Rights Act, which was signed into law just three months later. This is an important point for CJEF and others who support the relocation of the monument, as it demonstrates that the placement of the flag was not simply an act of historical memorialization but rather an overtly racist action in protest of desegregation. Per a report published in 2000 by the Senate Research Office of the state of Georgia, many Southern states began to raise the Confederate flag over their capitol buildings and other government properties as a kind of “intimidation of those who would enforce integration and a statement of firm resolve to resist integration.” Members of the Georgia Senate viewed the flag installations during this period as a direct response to the passage of the Civil Rights Act.To date, the only action taken by the county commission has been to replace the widely recognized “Southern cross” Confederate flag with the original, less well-known “Stars and Bars” design, as a form of compromise in lieu of relocation. The Stars and Bars was the first official national flag of the Confederacy.

Despite challenges and setbacks around the monument removal, CJEF plays a major role in the community in other ways. Members share that the group has provided a way for them to meet and connect with neighbors who want the best for their county. They find that the organization creates a space that allows for dialogue, exchange of ideas, and advocacy around the kinds of issues that are still rarely discussed in Walton County. This in turn allows members and partners to have hope for the future of the community.

Looking to the Future

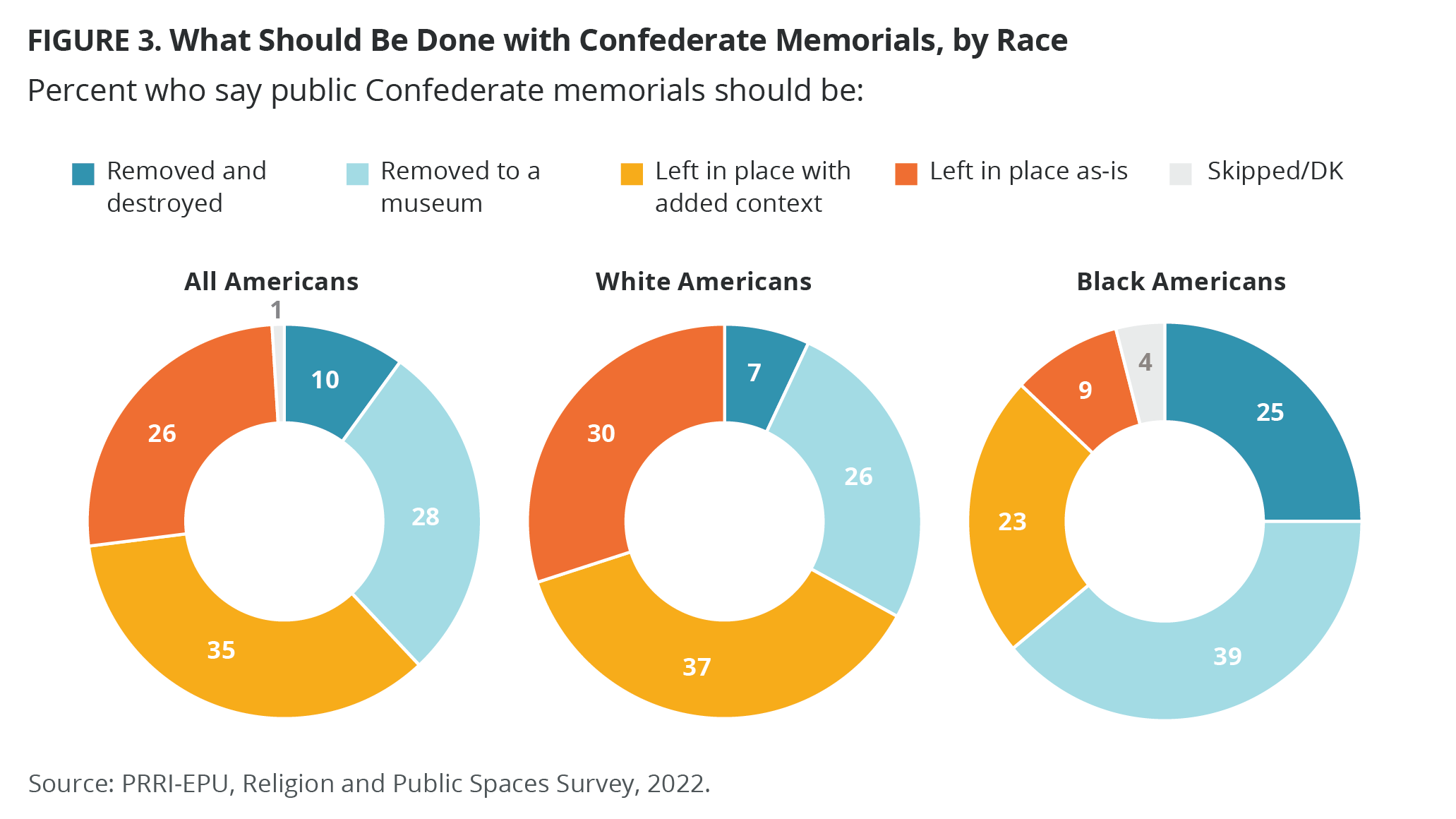

White and Black focus group participants were divided over what should happen to the Confederate memorials that are still in place. In our national survey, we asked respondents about four possible options concerning monument reform: leave monuments in place as they are; leave them in place but add historical context in the form of a plaque or other marker that explains the honoree’s role in Confederate history; remove the monuments and put them in a museum or in storage (but don’t destroy them); or remove the monuments and destroy them entirely.

The national survey showed that white and Black Americans have very different views on this topic. Three in ten white Americans (30%) say the statues should stay in place as they are, 37% say they should be left in place but have additional context added, 26% support moving the statues to a museum, and 7% say the statues should be removed and destroyed. Black Americans fall almost completely in the opposite direction: 9% say to leave the statues as they are, 23% say to leave them and add context, 39% support moving them to a museum, and 25% would like to see the statues removed and destroyed. Overall, 26% of Americans support leaving the statues as they are, 35% say leave them but add context, 28% say put them in a museum, and 10% say they should be removed and destroyed.

Focus group opinions provide additional insight into these figures. Many Black participants expressed a wish for the monuments to be removed and either destroyed or moved to a museum where they could be more fully contextualized.

“I feel like maybe they should take them down, but before they take them down why not add on a plaque to the statue, bring an awareness to all the messed-up stuff that that person has done. Instead of it being like a memorial in a good way, it’s like a remembrance of the wrong and all the bad things that have happened.”

Black man, Florida

Many white participants also expressed a desire for additional context, though fewer white participants wanted to see memorials removed, instead preferring that context be added to monuments where they presently stand.

“I don’t think necessarily Confederate statues should be torn down, but I think if there’s something educational that, like, people want to put up.… I think it just has to be done in a manner that’s empathetic to how it could affect everybody that’s going to come and look at this. And I don’t think necessarily when these statues were put up that anything was done in like a ‘Oh, this is really going to piss some people off like to do this.’ I don’t think people were thinking that, but I think now, I guess, when you put up a statue … that seems like I’m honoring maybe the negative things that were done in his name, but maybe I use a plaque and tell a story and give the information or something like that.”

White woman, Alabama

“I would still want access to those monuments, but the information at the base would have like the full story or why this statue is here in the first place, why it was moved, what we believe now to be, why our views have changed since then, so we’re not erasing, because we need to be able to learn from our mistakes.”

White woman, West Virginia

“I’d rather see a community come together and create an additional plaque or something that goes along besides that particular piece to explain who it was, what it was, what happened, and now today why things are different. Because wow, is that a teaching moment if you are a parent of young children, if you’re going to visit a new city and you’re visiting things like this, and maybe you’re from the Pacific Northwest and you’re not really familiar with what happened in certain parts of the South back in decades and decades ago.”

White woman, South Carolina

However, many white participants and some Black participants felt that taking any action regarding the monuments was unnecessary, or a waste of time and resources that could be put to better use. Some white participants felt the process would lead to a constant cycle of building and tearing down monuments once the members of a future generation decide they are offended by them. Several Black participants felt that taking down monuments or adding context to them would be empty gestures that did little to improve the economic situation or daily lives of Black residents.

“Honestly, I feel that the removal of the statues alone is not going to be effective…. The only real solution to this type of problem is to address the root, which is ignorance and racism. Hatred towards a group of people based on unknown, based on lack of information, your lack of familiarity, your own seemingly lack of ability to relate — those things need to be addressed before any of these other things will ever be seen as potentially problematic by anybody except who it affects directly.”

Black woman, Alabama

“I think that had America fulfilled its promises and contract with Black people post-slavery, these statues wouldn’t even exist. For every other group of Americans in American history who have been wronged in totality, the government has in some way attempted to make them whole, and that has never happened with Black people.”

Black woman, Louisiana

Adding context to memorials, whether in museums or in their current locations, seems to be the solution with the most common ground across states and racial groups. While white participants are generally unlikely to acknowledge how monuments are offensive to Black residents, many felt that added context would be helpful for explaining “both sides” of the story. Many Black participants felt that adding context would help tell the stories of past and present harms and help explain why many Black people consider Confederate monuments hurtful.

“The removal of some of the statues is understandable, but … history is history, and just because it’s not important to me doesn’t mean that it wasn’t important to somebody and that that is part of their history. But there has to be a common understanding that just because there’s a statue doesn’t mean that this person really is great or that they are good. But just because they’re not great or not good doesn’t mean that we have to disrupt the history of other people. That’s probably not a very popular opinion, but that’s how I feel.”

Black woman, Kentucky

THE 2022 DAY OF REPENTANCE

RICHMOND, VA

“There are a lot of hurts that have happened. There are a lot of hurts that are still happening. Have we as a city really repented for this?”

Katie St. Germain, The 2022 Day of Repentance

“When we look to the Bible, we do see that the Lord talks about generational sin. There are sins of our fathers that are handed down through the family line. We need to own that as family and atone for it, repent for it so that we can move forward.”

Katie St. Germain, The 2022 Day of Repentance

The 2022 Day of Repentance was an event that aimed at bringing about community healing through prayer, repentance, and forgiveness. The initiative was started by a lay parishioner who had experienced spiritual and physical healing after a personal journey of truth-seeking and repentance. They envisioned using a similar process within the Richmond community to help address the deep division in the city. A steering committee of local pastors and nonprofit leaders was formed to execute what became the 2022 Day of Repentance.

A service of prayer and reflection was held in September 2022 at a church on Monument Avenue, near a site where a monument of Robert E. Lee had stood for 131 years. This site had taken on a new significance following the death of George Floyd and the resulting unrest, which brought renewed intensity to an ongoing public debate about the collection of Confederate monuments along the city’s Monument Avenue. The statue of Lee, in particular, became a key gathering place for events, vigils, activities, and general efforts to bring attention to issues of race and equity. By the end of July 2020, the city had removed four of these monuments. But the state-controlled Lee monument would not come down until September 2021, and it fueled tensions for the additional year that it remained in place. To hold a service of repentance during the anniversary month of the monument’s removal, at the site where the monument once stood, was a powerful experience for the 85 community members who came together that morning. By design, the Day of Repentance set the tone for the inaugural Clergy for Racial Reconciliation Conference, which was held the following month, preparing the clergy for the work they would engage in during the conference.

The leaders of the Day of Repentance initiative see the Lee monument site as playing a key role in their work moving forward, owing to its symbolic connection to both faith and the Confederacy. According to the lead organizer, the Lee monument was the first on the Avenue, and it was funded through church organizing, sat on land donated by a church, and was erected in 1890 with a dedication and prayer service led by a Presbyterian pastor. Historical sources show that the dedication ceremony was attended by an estimated audience of between 100,000 and 150,000 people, who came from all over the South.

As the Day of Repentance steering committee gears up for the 2023 event, they have engaged in a lot of reflection. While many desire peace and healing, not all are on the same page about the idea that repenting for atrocities that took place before they were born is necessary. There is recognition among the initiative leaders that the words selected can impact the way people feel about and choose to engage with the service, and therefore the name of the initiative may change in the future. Regardless, the group is fully committed to the healing of their city and will continue to grow and shape this event to respond to the needs of Richmond.

How Religious Beliefs Frame the Discussion

As with other topics, there were distinct differences between the way the Black focus groups discussed religion and the way the white focus groups addressed the topic. Black groups were able to directly connect religion to the issue of racism and the question of how to organize for change, noting at times that white religious communities had often not been helpful in these efforts.

“Well, the Confederacy is a symbol of hate, hatred, and so … I’m going off of my Christian views, that would be one reason alone to feel like they should be removed. Because they do promote acts of hatred, acts of violence.”

Black man, Alabama

“My religious beliefs do influence me to see [the] Confederacy as … It’s like you’re rubbing it in our face or sitting it on a pedestal or something. Like, nobody wants to see this and this sparks hatred. Like, racism is nothing but hatred and negativity.… The flags just need to go. It’s not even positive. It’s just—on every level it needs to go.”

Black woman, North Carolina

Some Black participants also shared that they believe racial segregation within Southern religious communities contributes to the difficulty of addressing racism in the wider community, because it contributes to white Christians’ unwillingness to consider the perspectives and experiences of Black Americans.

“We have the church for the African Americans, we have the church for the Caucasians. I feel like here in Virginia it’s just divided.… So do I believe that church is, like, going to be the voice? No, because we learn two different things in two different ways because of our skin color. I don’t know how here — and I’m only speaking for Richmond — I don’t know how the church would help.”

Black woman, Virginia

At the same time, many Black respondents also said that their churches play an important role in preserving and teaching Black history and are essential voices in helping to change the debate about removing symbols of the Confederacy.

“The fact that we are in such a minority, the church has to step in. Because, as in any Black community, the pastors and the ministers, those are the leaders … I think, [who] were very instrumental in getting rid of Stonewall Jackson, which was initially a high school.… They made it a middle school and now it is West Side.”

Black woman, West Virginia

“The church plays an important role in preserving some of our history and teaching the history. Even today, while we may not talk a lot about the history … our pastor is really on it, getting us out there to vote, being aware of issues within the community, being very proactive.”

Black man, Georgia

Other Black respondents said that while church leaders remain essential in driving these conversations, ultimately the work involved in racial healing relies on community members themselves.

“I just think that we have to have those tough conversations. I think for a lot of Caucasian people, they may be scared to have that conversation because they lack the knowledge.… Then with the history of America being the way it is, it almost reinforces that misunderstanding.… I think it just has to start with understanding and knowledge. Really. That’s the foundation. With spiritual leaders, I believe that they could definitely help be that voice, help be that beacon, but I also feel like we all play a role in trying to curb this whole thing.”

Black Man, Tennessee

White groups had more to say on the role of churches and religious groups in the community, but generally did not make direct connections between religion and racism or the debate over monuments. They also tended not to mention religion playing a role in shaping attitudes about racism and inclusive public spaces.

“You could find plenty of people who are Christians who … don’t see any problem with these monuments and statues of people who were slave owners, who were racist…. [But] I don’t believe that Jesus would condone not even it so much as a graven image but just condone what it would stand for and all that kind of stuff, just condone the people behind what we’re celebrating, like what they stood for. That’s my thing. But on the other hand, there’s people, Southern Baptist Christians don’t see any problem with it, so maybe it’s a personal morality thing.”

White woman, Kentucky

“But, in my mind, my religion … is absolutely irrelevant, because public spaces and those memorials and the Confederate memorials, in my mind, just like the Founding Fathers of this country, there is a division between church and state.”

White man, Louisiana

However, a few white respondents did say that their faith leads them to have conflicted feelings about such statutes, or that their faith might lead them to believe that such monuments should be removed from public spaces because their presence is hurtful to their Black neighbors.

“I don’t know if connected, like, in a close manner with my religious beliefs. I think with my faith, like acceptance and welcoming in, like giving a loving, having that kind of identity. I guess would reflect with my religious beliefs. And I guess in a way, when I think about it, that’s a little bit of my mindset with my opinions on the statues and the Confederate statues and things like that. I guess in the aspect that if it’s hurting somebody, then put it somewhere else where it’s not hurting somebody. I guess maybe I could align that with my faith of trying to have the identity of being loving and welcoming to everybody. So I guess if you dig real deep, then that would be connected to my faith.”

White woman, Alabama

“I think, as a Christian, and wanting to live a life like Christ, it’s hard to walk through the street and see these statues of people who are being essentially idolized in our city that did things that are so against my beliefs.”

White woman, West Virginia

Religion as Morality and “Love Your Neighbor”

Both white and Black groups expressed the belief that churches are fundamentally doing good in their communities. Some participants in groups of both races said they think a small number of churches and pastors are just trying to make money, but, overall, most seemed to see churches and church leaders as far more trusted than political institutions and leaders.

“I’m pretty sure I would trust the pastor over an elected official…. I like seeing churches that do a lot of charity work, like Coats for Kids, and all kinds of different little things like that. They really add up, they really help the community. I used to do community service for a church I went to.”

White man, Mississippi

“Yeah, I think the church needs to understand its demographic and what’s around them and listen to the needs of what they can do to impact their area or their neighborhood, whether it’s sending people to the church to go volunteer at Feed More, or go ahead and go to the park and help plant trees or flowers, or just understanding your community and how you can benefit them.”

White man, Texas

ST. PAUL’S EPISCOPAL CHURCH

RICHMOND, VA

In light of our Christian faith, we will trace and acknowledge the racial history of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in order to repair, restore, and seek reconciliation with God, each other and the broader community. Mission Statement of St. Paul’s History and Reconciliation Initiative

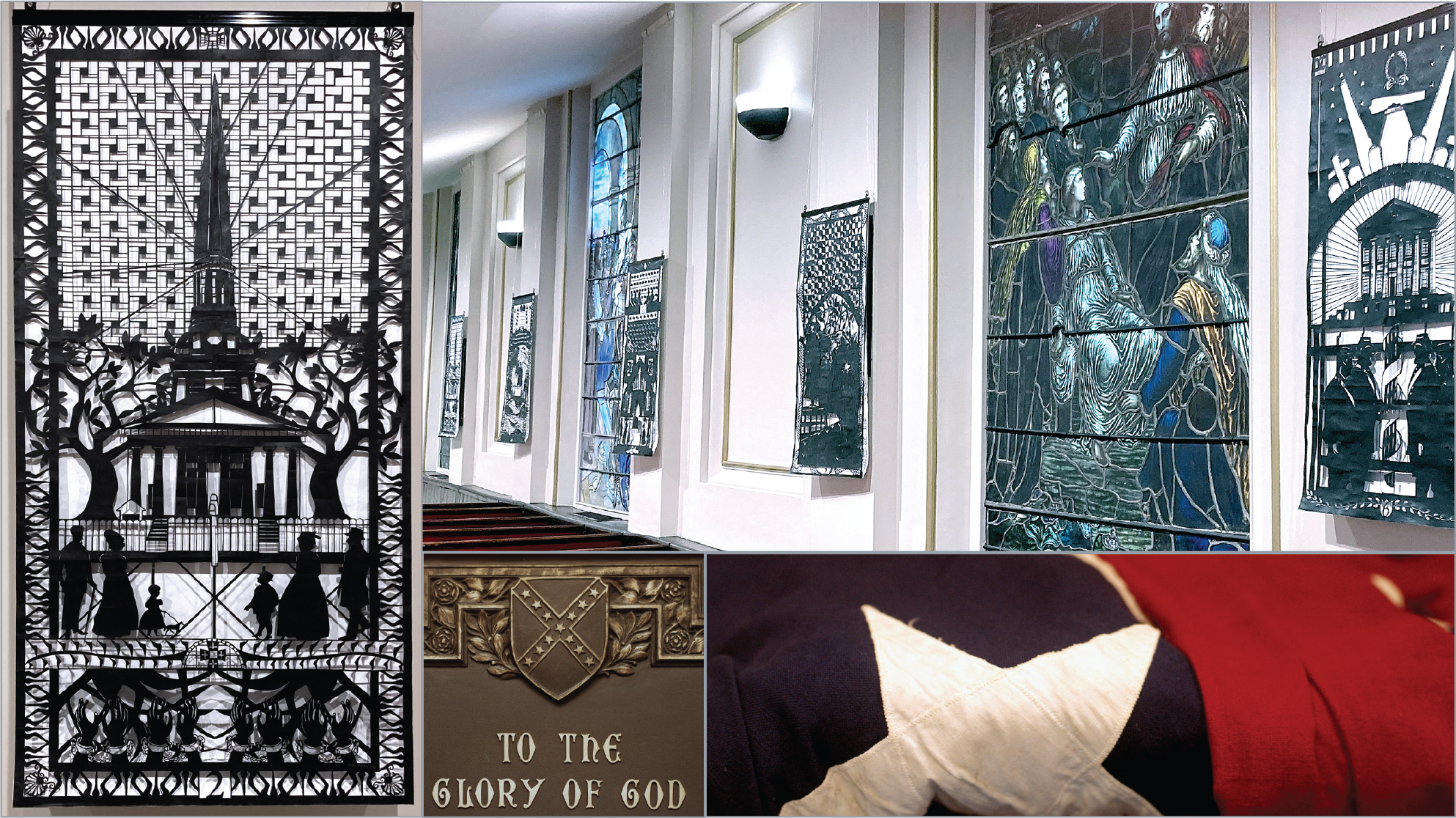

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church of Richmond, once known as the “Cathedral of the Confederacy,” embarked in 2015 on a process of truth-seeking, reckoning, and reconciliation around its racial history. These efforts have been transforming the church and its work.

St. Paul’s once counted Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis as communicants and held massive funeral services for Confederate leaders. Plaques, flags, and kneelers with Confederate battle flag motifs were once displayed throughout its building. Today, St. Paul’s has done years of historical research, hosted dialogues and prayerful conversations on the subject of race, held services of lament and reconciliation, and facilitated the creation of new artwork, music, and a book about the church and its racial history.

The building, which is a Virginia Historic Landmark and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, was constructed in 1845 across the street from the Virginia Capitol, which, during the Civil War, became the capitol building of the Confederacy. After the war, St. Paul’s became known as a shrine for those embracing the Lost Cause. Still, over many decades, the church also became known for its community outreach in many areas, including education, housing, food insecurity, and health.

After the 2015 massacre at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, church members began to take a closer look at whether St. Paul’s was as welcoming to all people as they wanted it to be. In 2016, the church established the History and Reconciliation Initiative (HRI) to examine the roles of race, slavery, and segregation in the history of the church and to discern their ongoing legacies today.

Over the past seven years, the congregation of St. Paul’s has pored over extensive church records, attended presentations about the findings, and held discussions to process what they were learning — including a public forum in which the presiding bishop of the U.E. Episcopal Church participated. Parishioners went on pilgrimages to Selma and Montgomery, in Alabama, to deepen their understanding of the civil rights movement. HRI committees hosted “prayerful conversations,” which allowed the church to collectively decide what they wanted to value moving forward. One result was the congregation’s decision to remove all vestiges of Confederate identity from its building. Wall plaques and kneelers with battle flag motifs or images associated with Lost Cause sentiment were removed from display and stored in the church’s archives. Additionally, stained-glass windows initially dedicated to Confederate leaders were rededicated to the glory of God.

Today, St. Paul’s has new memorials on display. In 2020, after protesters spray-painted the names of victims of police brutality on the front steps of the church, the congregation decided to leave the names there, as a reminder of the need for continued work toward justice and equity. The church also commissioned an art installation called the Stations of St. Paul’s as part of a prayerful liturgy of acknowledgement, lamentation, and reconciliation. The installation is made up of fourteen unique pieces of art that depict moments in the church’s history related to racial issues. They are displayed in the sanctuary each Lent for visitors and congregants to reflect upon.

While the official initiative has concluded, St. Paul’s aims to incorporate the lessons it learned from the HRI effort into its mission today and going forward. Its Community Engagement Ministry continues the work of discovery, atonement, reconciliation, and healing started by HRI, and the church offers support to other faith-based groups wishing to embark on a similar journey.

Groups of both races discussed how religion guides their moral compass, particularly regarding the principle of loving your neighbor. This concept, in particular, creates an opportunity for starting discussions about finding common ground.

“I truly in my heart of heart believe that that is probably the only way that there is restoration is that if Word says, kind of reconciliation. There has to be that where we repair relationships and I think that I truly believe that the man of faith, that God can do that.… That has to come from Black churches and white churches, and there has to be something in the middle.”

Black man, Virginia

“I think there’s a spot for communities and religious communities to come together and work together as one organization, because I guess, again, when you think about it, there’s more power in numbers.”

White man, Kentucky

“I think that the basis of most people’s faith is love, and when you lead with love and when you see your fellow person as a person, as a human, you’re empathetic to what they’ve gone through, who they are as a person.… When it comes to discussions like we’re having, I think that we as a people have been some of the most forgiving, resilient, welcoming people, in spite of everything. And I think that we still, despite of a lot of the things that are said in the media, a lot of the betrayals from the Black community that the media portrays that we’re aggressive and all these other things, I think when you really sit back and look at it, it shows that we lead with love.”

Black woman, South Carolina

Moving Forward: The Role of Race and Religion in Building New Public Spaces

The national survey shows that an overwhelming majority of Americans support “efforts to tell the truth about the history of slavery, violence, and discrimination against racial minorities in their communities,” including 90% of white Americans and 89% of Black Americans. Substantial majorities also support “efforts to promote racial healing by creating more inclusive public spaces in their communities,” including 77% of white Americans and 87% of Black Americans. However, the focus groups made clear that the pathway to resolution is complex, and there are considerable differences between these racial groups on the question of how to approach public spaces — particularly in the case of Confederate memorials. The results of the focus groups suggest that any policy solutions aimed at realizing the vision of inclusive public spaces will need to take into account major racial differences on this issue.

Acknowledging Race and Racism

It was clear in the focus groups that the white and Black participants had vastly different levels of awareness and comfort when discussing their racial identity. Black participants would frequently jump right to discussions of Confederate memorials when talking about public spaces, even before the moderator broached the topic, while white participants had to be directed to consider the memorials. Black participants were very open about their own experiences with racism and how the memorials hurt them.

“Those monuments and all the symbolism, all of that, it was all meant for intimidation. It was to control the populations of people in those towns and those areas and to assert the authority of the groups that they represent. It was to instill fear and control, that’s what it was all about. They did not want to lose their place in authority. And even with losing the war, they put these things there to keep — every time a Black person walked by, to remind them, you know, ‘This is what happened. You know we’ll fight for ours. You know what we’ll do to you.’ That’s what it was about. And also to keep that legacy alive with their children.”

Black woman, West Virginia

“My grandparents lived well into their 90s, so I have the unique, I guess, history of my mom and my parents and what they went through, my grandparents and what they went through. I think it was last year … we actually found slave documents of where our family was willed to the families of the slave owners. It’s actually a will and testament in detail, willing our family to the slave owners and what happens if one dies, it’s replaced with another one, just like its property, which we were considered.”

Black woman, South Carolina

“It’s kind of bad that I’m learning it at my age…. If you lived anywhere outside your state, then you learn a whole lot of history, how racism is, what Jacksonville was, and the way they were doing Black people back in the days. I never knew that. I was born and raised [here], and I’ll tell you, it shocks me. It makes me angry to learn that those statues are up there, and it has something to do with racism. It’s not right. It’s not right.”

Black woman, Florida

The national survey puts numbers to these sentiments: 20% of Americans say they have personally experienced hostility or discrimination based on their race, ethnicity, or skin color in the past few years. This number is more than four times as high among Black Americans (43%) as it is among white Americans (10%).

While most white focus group participants were defensive about the memorials and generally wanted to leave them alone, a few did recognize that the memorials might be problematic for Black people. Particularly in Richmond, where memorials had been removed, white participants recognized the hurtful nature of the monuments.

“I grew up in Richmond and I would go see those monuments for like the Easter Parade and all these different things, and I never thought twice about it until I was older and started learning about it in school. And that’s when I started having negative associations with them.”

White woman, Virginia

“After learning how so many of these monuments were built so long after the Confederacy, too, and kind of learning about why these monuments were put in the strategic locations they were put in the first place, kind of more to instill fear in people.… I don’t know if I think it’s erasing history by putting them more in a private space or moving them altogether when they’re definitely like a hate symbol towards some people.”

White man, Virginia

“I think we have a duty to correct the errors of the mistakes we’ve made in the past.… I don’t think it’s something that we have to appease everyone with, but I also feel like you should make something right.”

White woman, West Virginia

Even with these realizations, though, some white participants were unsure of the best solution. On one hand, they thought keeping the statues would be a reminder of America’s dark past. On the other hand, they acknowledged that the presence of the statues could be harmful and offensive.

“We cannot erase our history and that’s just — that’s part of our history. I don’t think any of it should be taken down. It’s just certain people feel a certain way about certain things, and that’s just our history. We can’t help that.”

White woman, Arkansas

ORLEANS LEGACY PROJECT

NEW ORLEANS, LA

“Markers are important in bringing forward the conversation about how this is not just history, but it’s living with us today, and we have a responsibility to recognize it as the same thing, the same use of white supremacy to oppress and subjugate Black people.”

Dr. Becky Meriwether, Orleans Legacy Project

“Mass incarceration is the latest face [of oppression], along with police brutality and vigilantism. And all of these things have been alive and well in the much more recent history of this city, and certainly this nation.”

Dr. Becky Meriwether, Orleans Legacy Project

The Orleans Legacy Project (OLP) is a grassroots organization that aims to support racial reconciliation and healing by memorializing victims of racially motivated lynchings in the New Orleans, Louisiana, area. The group started as part of the Community Remembrance Project of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), which supports local groups involved in this kind of work by providing assistance with soil sample collection from locations where lynchings were carried out and historic marker installations at lynching sites.

The OLP began meeting in the fall of 2018 to research the history of extrajudicial killings in New Orleans. The group selected the 1900 Mass Lynching, also known as the Robert Charles Massacre, as the first historical incident to focus on, because it embodied so many of the issues at the core of racism and injustice: white supremacy, Jim Crow, lynching, and mass incarceration. Additionally, members felt that the incident was a representation of the way those issues still show up today. Prior to the massacre, local law enforcement had offered a reward for the capture of Robert Charles, who was wanted for murder. The search for Charles developed into a white mob of rioters that terrorized the city for four days, ending in the deaths of Charles, a 60-year-old grandmother named Hannah Mabry, and several others, in addition to many injuries. Contemporary news articles contain some discrepancies on the total number of killed and injured, but they agree on the fact that most of the victims were Black.

OLP collaborated with EJI and with historians who had previously worked on historical markers that told the story of the trade of enslaved persons. Their task was to determine how to relay the complex story of the massacre in a meaningful way within the word constraints of the marker.In December 2020, in a ceremony that included statements from a city councilman, a state representative, and the mayor, OLP unveiled a historical marker memorializing the 1900 Mass Lynching at the intersection of Oretha Castle Hailey Boulevard and Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in New Orleans. This location was selected for several reasons. It is near the actual site of the massacre, but it’s also in a spot well-traveled by both tourists and locals. This makes it more accessible and increases opportunities for the public to engage with and learn from the marker. The location is also along the path of a Civil Rights trail that has been conceptualized for MLK Boulevard, providing the opportunity for it to be included in that trail once that project is developed. The marker is also across the intersection from the existing MLK memorial. All of these factors were key in deciding the placement — a decision that was made in conjunction with city planners and an advisory group associated with the mayor’s office. The dedication ceremony also included a calling of the ancestors by Kumbuka African Drum & Dance Collective and a remembrance ceremony with a descendant of Hannah Mabry. Since then, the group has collected a soil sample from the site of the 1893 William Fisher lynching, held a remembrance ceremony for him, and started work on plans for the installation of a historical marker.

The Orleans Legacy Project is a powerful example of how just a few people can have an impact on an entire community. The work that they have started has provided a pathway for further engagement and conversation around how to discuss and share New Orleans’ history moving forward, as the community continues to voice a desire for transparent and inclusive acknowledgment in public spaces.

Trust and Building Community

Even though the national survey shows that a majority of Americans agree with statements “I try to build relationships with people of a different race than me” (87%) and “I try to respect and learn from the views of others, even if I disagree with them” (93%), a common sentiment among all the focus groups was cynicism toward others. Neither the Black nor the white groups seemed to trust the other. This again speaks to the idea that despite people having shared visions for the future across racial lines, the plans could fall apart during any actual implementation.

On a more positive note, white groups in places where monument debates and removals have already occurred were more sensitive to how memorials affect Black people, even if they did not necessarily agree with the action taken with local monuments. As noted above, white Richmond participants acknowledged the racial division in ways that did not happen in most other places. In the white Louisiana group, some participants from New Orleans, where removal debates have taken place, supported removal.

Another encouraging sign for the possibility of creating community came from some of the Black participants, who described having difficult conversations about race with white people.

“Just to see an educated Black person, white people are shocked. Like, ‘Oh my gosh, you work at the school? Are you an assistant?’ I’m like, ‘No, I’m a teacher. I’m a whole teacher.’ They’re not used to that and so for them to even see me over there, it’s like, Oh, OK, well she’s not like them. They’re actually open. And I hate it’s even like that, but it’s the world we live in, right? So for them to even come and try to have that conversation, it’s like, OK … you’re actually seeking to understand. The area that I came from was majority white and I even had some of my white softball teammates get in touch and say `Hey, girl, I’m just reaching out to you to see how you’re taking this whole George Floyd thing.’ And maybe that’s not the case for everybody, but I had a bunch of people reach out to me and from 2020 up that I haven’t talked since over 20 years that are just, like, seeking to understand.”

Black woman, Mississippi

“My boss was a younger white guy, and we used to have to drive around the state to the different counties to do—I worked for the health department, so we drive around the city and do different things. And we were on our way somewhere and he asked me, ‘What is the deal with Black people and the Confederate flag? I don’t get what the deal is.’ … Now he was a truck-driving, rifle rack in the back, Confederate flag on the license plate. After we had the conversation, he told me, he said, and he was in his mid-thirties then, and he said, ‘You’re the first Black person I felt comfortable [enough] to ask these questions to.’ And he’s 30-something years old. Knows a lot of Black people, works with a lot of Black people around, Black people all the time, he said, but you’re the first one I felt comfortable enough to ask the question…. When he came to work the next day, the gun rack was still in the back of truck, but that Confederate flag was gone. He’s a war history buff. He said, ‘It really was about the heritage,’ he said, ‘but I did not realize I was offending you.’”

Black woman, South Carolina

The national survey shows that nearly six in ten Americans (58%) agreed with the statement “When Confederate monuments are removed, communities should create new public monuments and art that represent the values of racial equality and inclusivity,” including 51% of white Americans and 77% of Black Americans.

LANE CENTER FOR SOCIAL AND RACIAL EQUITY

MACON, GA

“I think making history visible is important. What we’re talking about is hidden history, occluded history, things that have been erased, erasure of certain history selectively.”

Dr. Melanie Doherty, The Lane Center for Social and Racial Equity

The Lane Center for Social and Racial Equity houses the diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice work of Wesleyan College in Macon, GA. Also known as the Equity Center, it aims to support Wesleyan in its commitment to foster an anti-racist campus and create new opportunities for the college and Macon residents to build community together. The Equity Center was formed as part of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s Crafting Democratic Futures Project — a cohort of college and university centers working to create frameworks for reparative justice. For the Equity Center, the first step in this process is telling Macon’s collective story in a way that honors and acknowledges the city’s history in its fullness.

The year 2023 marks Macon’s 200th anniversary, a milestone that has been and will continue to be marked with cultural, educational, and entertainment events throughout the year. The bicentennial provides a special opportunity for the Equity Center to advocate for inclusive approaches to historic storytelling in order to lay a new foundation for the way the city understands its history moving forward. Through a series of community discussions in 2021 and 2022, the Equity Center worked with key stakeholders from different segments of the Macon community to identify their priorities, concerns, and ideas for maintaining the things they love about their city while finding effective solutions for the things they would like to improve. As a result of this work, the Equity Center and members of the community group are collaborating with the Macon Bicentennial Subcommittee on Historic Markers. Through this collaboration, the Equity Center has been able to support the subcommittee in centering racial history, based on the idea that both accomplishments and atrocities must be acknowledged and discussed in order to repair past injustice and set the stage for a more equitable future.

The Bicentennial Subcommittee on Historic Markers voted to install three historic markers as the first phase of what is intended to be a long-term, ongoing effort to make the official recognition of Macon’s history more inclusive through the use of historic markers. The initial phase will include markers that highlight the contributions that Black people have made to the community, such as noting Historic Cotton Avenue, an area that was once home to a thriving district of Black-owned businesses. Additionally, there will be markers that acknowledge atrocities, such as one on Poplar Street, which will identify a site in downtown Macon where enslaved people were once sold.

The sites will be marked with a bronze plaque that will provide a brief historical summary. Attached to the plaque will be aluminum QR codes. Scanning the QR code will connect visitors to a database of oral history recordings, maps, photographs, and additional facts about that specific site. The database will be housed in the digital archives of Wesleyan College.

How to Create Consensus

The evidence here shows that efforts to build bridges across the racial divide and to have discussions about redesigning public spaces and removing Confederate memorials will largely rely on conversations between individuals. White people need to hear about the experiences that Black people have and listen to their views on the subject. The focus groups revealed that many white participants simply did not understand how Black people saw the issue and showed that, in some cases, their views had changed when they gained understanding.

At the same time, Black participants felt frustrated by the continued patterns of racism in their lives, and some had no interest in taking on the burden of educating white people about why they find Confederate memorials offensive. Yet others were willing to take on the difficult conversations and work toward consensus.

LAFAYETTE COMMUNITY REMEMBRANCE PROJECT

OXFORD, MS

“This kind of group is such a model for how we can do this work together, how to build beautiful things from a terrible history.”

April Grayson, Lafayette Community Remembrance Project

The Lafayette Community Remembrance Project (LCRP) is a grassroots organization dedicated to memorializing victims of lynching in Lafayette County, Mississippi. The group uses the Equal Justice Initiative’s (EJI) model of soil collection and historical marker installation to publicly acknowledge the physical sites of incidents that shaped the previously little-discussed history of the county.

LCRP can trace its roots to a 2017 presentation by a researcher at the Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project at Northeastern Law School. The presentation told the story of Elwood Higginbottom (sometimes spelled Higginbotham), the victim of the last recorded lynching in Lafayette County. Higginbottom’s story had touched the community before, when it was the subject of an op-ed published in the local Oxford Eagle paper in 2015. Building on that two years later, the presentation was received enthusiastically and sparked the development of the LCRP.

Members of LCRP have made it their mission not only to memorialize victims of lynching but also to create spaces and opportunities for dialogue, learning, and reckoning around Lafayette County’s racial history. The LCRP has a regular presence at the annual Juneteenth celebration and leads outreach to local students during Black History Month. With EJI, the group also supported a scholarship contest for high school students. In 2018, the LCRP held its first soil collection ceremony, in memory of Elwood Higginbottom, and later that year installed a historic marker near the lynching site. Since then, LCRP has conducted three more ceremonies to collect soil, in remembrance of three other lynching victims: William McGregory, William Steen, and William Chandler. Most significantly, the group successfully advocated for the installation of a memorial on the Lafayette County Courthouse lawn to recognized each of the county’s seven known victims of lynching. That marker was installed in 2021, and a large public dedication event was held on the courthouse square in April 2022.

Even with the hard-earned success around soil collections and marker installations, many in LCRP most cherish the relationships and bonds that they have formed with the families of victims during this work, and the way the work has also brought the community together. The marker unveiling for Elwood Higginbottom in October 2018 brought together 500 county residents of different races, backgrounds, religions, and ages, including nearly 45 members of the Higginbottom family. A family member of William Steen heard about the work and joined the Steering Committee. The dedication on the courthouse lawn attracted individuals that some LCRP members never thought they would see participate. All in all, the work has offered a pathway toward healing, not just for the families of the victims but for the broader community. In 2023, the group completed a strategic planning process to set a path for its work for years to come.

[1]The survey details and methodology are available in the onliappendices.

[2]The full screener is included in the appendices.

[3] These cities are Birmingham, AL; Little Rock, AR; Jacksonville, FL; Atlanta, GA; Louisville, KY; New Orleans, LA; Jackson, MS; Raleigh-Durham, NC; Charleston, SC; Nashville, TN; Dallas-Fort Worth, TX; Richmond, VA; and Charleston, WV.

[4] These states include all the states that make up the former Confederacy: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia, with the addition of the border states of Kentucky and West Virginia.

Focus Group Methodology

In partnership with E Pluribus Unum (EPU), PRRI conducted 26 focus groups to understand how residents think about public spaces in their communities and about the legacy and future of Confederate monuments. Each of the focus group meetings took place over Zoom from May 3 until July 14, 2022 across major cities in 13 states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia. See the number of participants below.

Participants were divided by race: one white group, with a white moderator, and one Black group, with a Black moderator. Having all-white and all-Black groups created a safe space in which participants were less likely to self-censor their views. Moderators moved participants through open-ended questions across four key topics modules: (1) introductions and ground rules, (2) overview of the community and feelings towards it, (3) debates on Confederate memorials and public space, and (4) public space ideal types. Moderators kept discussions within ninety minutes.

PRRI and EPU distributed screeners to identify the most representative participants in the study who reside in a metropolitan area, with a mix of various age groups and gender parity. Other qualifications for participants included having any religious belief as the most important or one of the most important parts of their life and self-identification with a political party. The number of strongly aligned Democrat and Republican respondents were capped. For those who met these qualifications, respondents were stratified on their education level, marital status, and political leanings (outside of party names).