March 16 marks the first anniversary of the Atlanta spa shootings, when a 22-year-old white man named Robert Aaron Long murdered eight people, including six Asian American women: Daoyou Feng (age 44), Hyun Jung Kim Grant (age 51), Suncha Kim (age 69), Soon Chung Park (age 74), Xiaojie Tan (age 49), and Yong Ae Yue (age 63). The shooter’s killing spree took him to three massage parlor businesses across two counties. Among the eight deaths, five were owners or employees of the targeted businesses, two were customers, and one was a passerby.

Stop AAPI Hate, an online reporting portal, has tracked the explosion of anti-Asian hate incidents that began with the COVID-19 pandemic. Two-thirds of those who have reported incidents are women. As Jenn Fang wrote in a February 25th blog post, the targeting of Asian American women is often based on the assumption that they are easy marks. PRRI data from 2020 and 2021 revealed a growing belief among Americans that a rise in violent anti-Asian rhetoric contributes “a lot” to violent actions in society. Examples of violent rhetoric include U.S. government officials blaming the Chinese for the spread of SARS-CoV-2, or what some, including former President Donald Trump, dubbed the “China virus.” In 2020, 51% of Americans saw a strong link between anti-Asian rhetoric and violent acts; in 2021, that share rose to 60% of Americans.

One year after the Atlanta shootings, and 14 months after an attempted insurrection to obstruct the peaceful transfer of power to a president who has not embraced anti-Asian statements, what has changed?

Many hoped that the violence would decrease. But it seems those hopes have not been borne out. According to the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism, the number of anti-Asian hate crimes increased 339 percent in 2021 compared to the year before. In the first two months of 2022, the gruesome deaths of Michelle Go on a New York City subway platform and Christina Yuna Lee in her Chinatown apartment, and the shooting death of two Chinese American women in New Mexico massage parlors, speak to the persistence of anti-Asian violence, especially targeting women.

As Fang notes, perpetrators are unlikely to face serious punishment under hate crime and nondiscrimination laws, which are ill equipped to prosecute anti-Asian bias. The prosecution of the Atlanta murders illustrates this ongoing confusion. In Cherokee County, where Long shot and killed four people, including two Asian women, the district attorney (DA), a white woman, has refused to pursue hate crime charges, finding no evidence of racial intent. By contrast, the Black woman DA in Fulton County, where Long killed four Asian women, is pursuing prosecution as a hate crime.

The history of prosecution of hate crimes against Asian Americans is short and spotty. The first federal civil rights trial involving an Asian American was the 1983 murder of Vincent Chin, a 27-year-old Chinese American man beaten to death by two white autoworkers who were angry at Japanese car manufacturers for creating competition and job losses in the Detroit-based auto industry. The men bludgeoned Chin to death with a baseball bat on the night of his bachelor party, while yelling, “It’s because of you little motherf***** that we’re out of work.” After the two perpetrators received no jail time and suspended sentences, activists fought hard for the Justice Department to take up the case as a civil rights matter. They successfully convinced federal officials to prosecute the men on hate crime charges, but neither one ever served any jail time.

In the years since, it has remained rare for attacks on Asian Americans to be prosecuted as hate crimes. Many think the persistence of the model minority myth to describe Asian Americans still makes it hard for some white Americans to believe that Asians can be targets of racism and violence. A similar tendency to reject the existence of structural racism causes many white Americans to downplay the severity of racism against Black Americans, who remain the most targeted group in terms of hate crimes in the United States. PRRI polls over decades have shown that white American Christian churchgoers are consistently more likely to deny the existence of structural racism than white people who do not go to church.

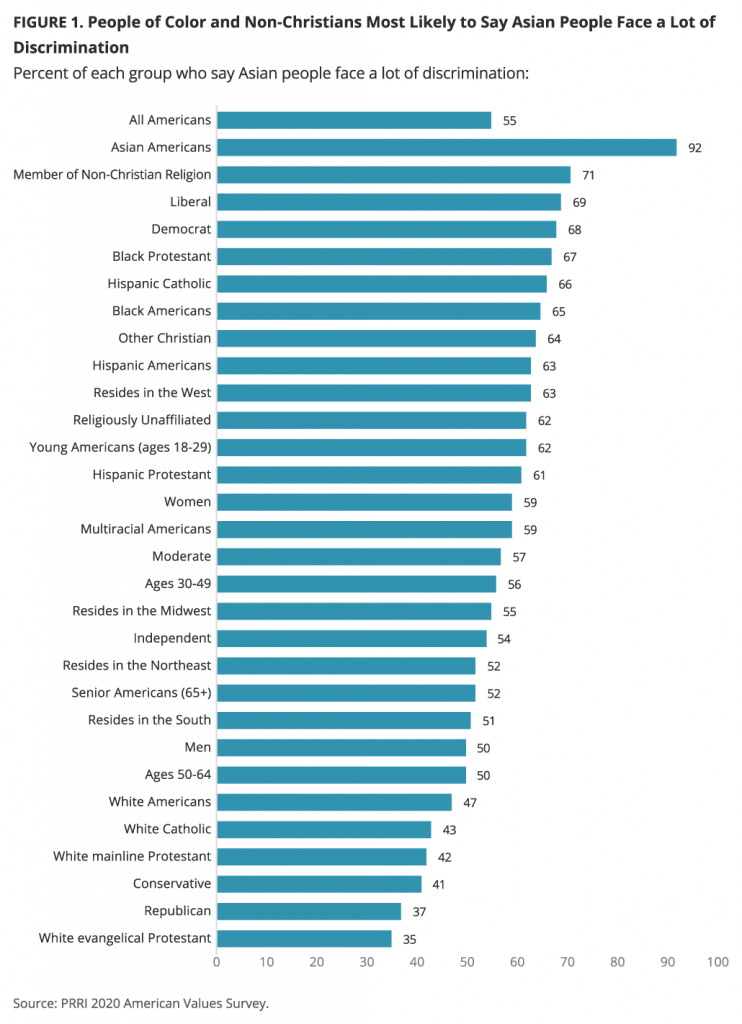

As the differences between the DAs in Cherokee and Fulton counties suggest, hate crimes are also in the eyes of the beholder. The two DAs could also be influenced by the politics and composition of their communities, particularly their local white evangelical populations. PRRI’s 2020 Census of American Religion data showed that white evangelicals made up 32% of Cherokee County’s population, compared with only eight percent of Fulton County’s. (For context, PRRI’s 2020 American Values Atlas showed that white evangelicals make up 14% of the population nationally.) White evangelicals were the least likely of any racial and religious group to agree that Asians faced significant discrimination in the United States. Only 35% of white evangelicals agreed with that statement, along with 37% of Republicans. By contrast, virtually all Asian Americans (92%), a large majority of Democrats (68%), and a smaller majority of all Americans (55%) agreed that Asians face significant discrimination.

Jane Hong is a member of the 2021-2022 cohort of PRRI Public Fellows.