The Coronavirus Pandemic’s Impact on Religious Life

The coronavirus pandemic has forced Americans to rethink everyday activities that involve getting together with other people, including religious gatherings, celebrations, and holidays. Whether and how religious Americans gather has been the subject of considerable debate throughout 2020, and without national guidance in place, practices have varied based on state and local restrictions. Most religious groups see the pandemic as a substantial concern, but the politicization of the pandemic has resulted in great differences in support for restrictions, perceptions of trustworthy authorities, and religious practices.

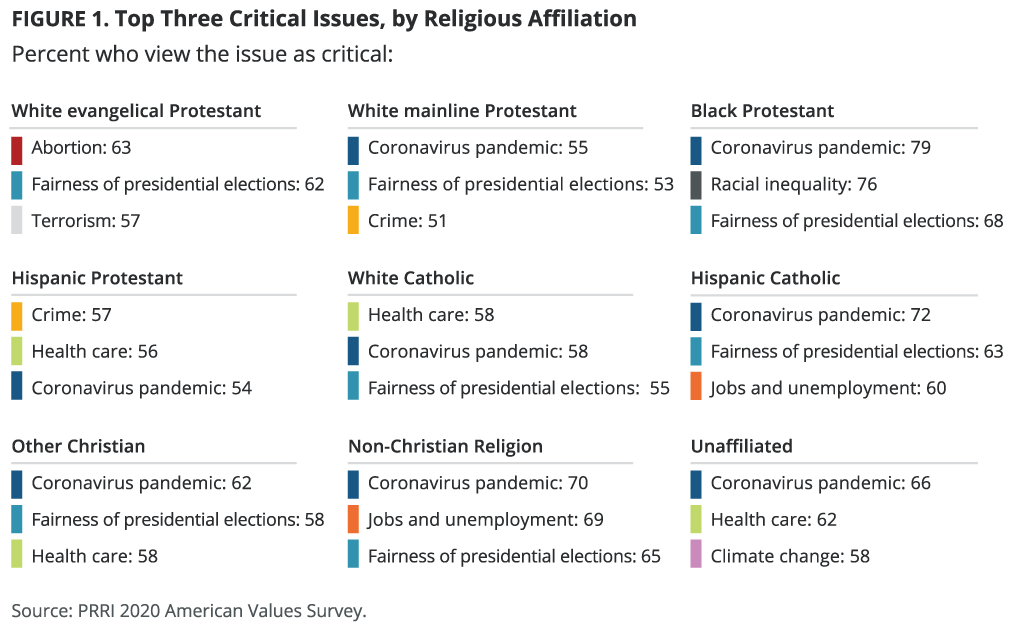

Perceptions of the Coronavirus as a Critical Issue

A majority of Americans (60%) and majorities of most religious groups say that the coronavirus pandemic is a critical issue. The pandemic is a top concern among Black Protestants (79%), Hispanic Catholics (72%), members of non-Christian religions (70%), religiously unaffiliated Americans (66%), other Christians (62%), white Catholics (58%), white mainline Protestants (55%), and Hispanic Protestants (54%). White evangelical Protestants are the only religious group for which the coronavirus pandemic does not rank among the top three issues, with only 35% saying the issue is critical.

Feelings of Connection With Religious Community During the Pandemic

Among Americans who attend religious services at least a few times a year, nearly half (47%) say they feel less connected to their religious congregation since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, about one-third (32%) say they feel about the same level of connectedness, and about one in five (21%) say they feel more connected. These patterns hold across most religious groups, except for white evangelical Protestants and white Catholics, who are more likely to say they feel less connected (54% and 55%, respectively) and less likely to say they feel more connected to their churches or religious congregations (10% each).

Among Americans who say they attend religious services at least a few times a year, a majority (56%) say that the place at which they primarily attend religious services is currently holding in-person indoor services, compared to 43% who say their church or religious congregation is not holding in-person indoor services. [1]

About three in four white evangelical Protestants (77%) and white Catholics (74%) say that the place at which they primarily attend religious services is currently holding in-person indoor services, compared to less than half of Hispanic Catholics (49%) and white mainline Protestants (47%) and only about three in ten Black Protestants (28%).

Two-thirds of Republicans (66%) and nearly six in ten independents (57%) say that the place at which they primarily attend religious services is currently holding in-person indoor services, compared to 44% of Democrats.

Majorities of Southerners (57%), Northeasterners (59%), and Midwesterners (66%) are notably more likely than Americans who live in the West (43%) to say that the place at which they primarily attend religious services is currently holding in-person indoor services.

Among those who say that the place at which they primarily attend religious services is currently holding in-person indoor services, nearly half (47%) say they feel less connected to their churches or religious congregations since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, while nearly one-third (31%) say they feel about the same and 23% say they feel more connected. Among those who say that their congregation is not holding in-person indoor services, a similar 48% say they feel less connected to their churches or religious congregations, 33% say they feel about the same, and 19% say they feel more connected.

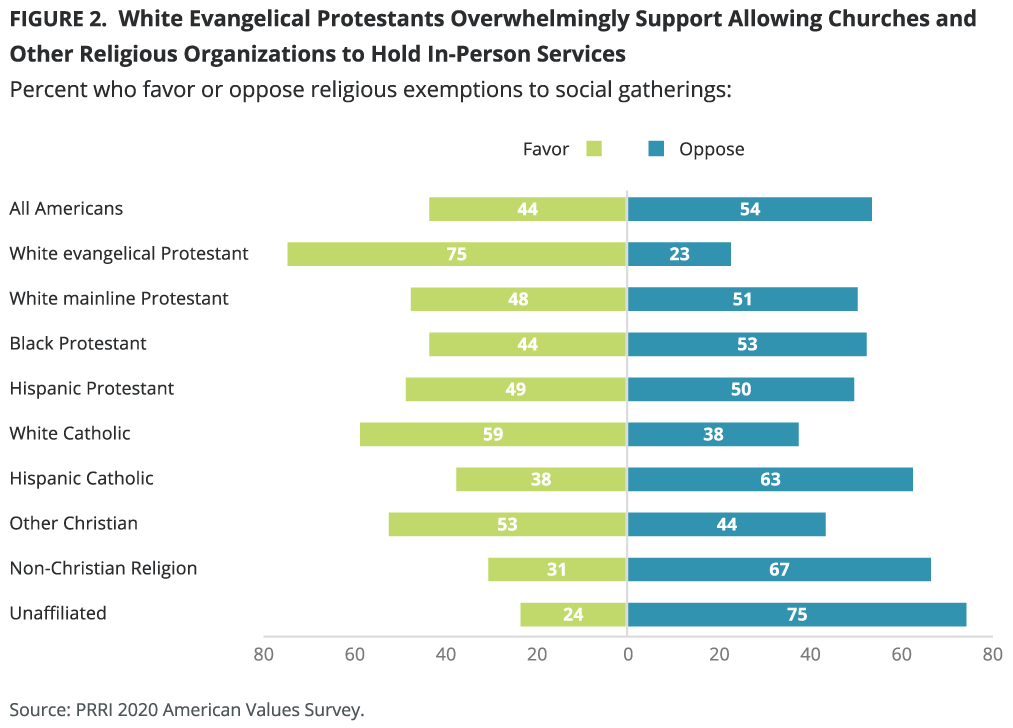

Religious Exemptions to Social Gatherings

More than four in ten Americans (44%) favor allowing churches and other religious organizations to continue to hold in-person services, even when the government has issued orders that limit social gatherings because of the coronavirus, compared to a majority of Americans (54%) who are opposed.

White evangelical Protestants (75%) and white Catholics (59%) are the only major religious groups among whom majorities believe that churches should be able to hold in-person services even when the government has issued orders limiting social gatherings. Substantial majorities of Hispanic Catholics (63%), non-Christian religions (67%), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (75%) oppose allowing churches and other religious organizations to continue to hold in-person services. Other religious groups are more evenly divided on this question: white mainline Protestants (48% favor vs. 51% oppose), Hispanic Protestants (49% favor vs. 50% oppose), Black Protestants (44% favor vs. 53% oppose), and other Christians (53% favor vs. 44% oppose).

Americans who attend religious services at least once a week are about twice as likely as Americans who seldom or never attend religious services to favor allowing churches and other religious organizations to continue to hold in-person services, even when the government has issued orders that limit social gatherings because of the coronavirus (64% vs. 33%). Americans who attend religious services once or twice a year or a few times a year are evenly split on this question (49% favor vs. 49% oppose).

Republicans (71%) are nearly three times more likely than Democrats (27%) to favor allowing churches and other religious organizations to continue to hold in-person services, even when the government has issued orders that limit social gatherings because of the virus. Independents fall in between, with 42% favoring this policy.

Southerners (50%) and Midwesterners (45%) are more likely than Northeasterners (37%) and Westerners (39%) to favor allowing churches and other religious organizations to continue to hold in-person services.

Beliefs About the Pandemic

Belief That God Will Protect the Faithful

About one in four Americans (23%) agree that “God always rewards those who have faith with good health and will protect them from being infected by the coronavirus,” while three in four disagree (76%), including a majority who strongly disagree (56%).

Black Protestants (52%) and Hispanic Protestants (39%) are most likely to agree that God will protect the faithful from the coronavirus, although notably these groups are also among the most likely to report always wearing a mask when they go out in public and to say that shutdowns, mask mandates, and other actions are reasonable attempts to protect people.

Less than three in ten white evangelical Protestants (29%), Hispanic Catholics (29%), and other Christians (23%) agree. Even fewer white mainline Protestants (19%), non-Christian religious Americans (17%), white Catholics (15%), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (10%) hold this view.

Americans who attend religious services once a week or more (29%), or those who attend once or twice a month or a few times a year (33%), are about twice as likely as those who seldom or never attend religious services (14%) to agree that God will protect them from the coronavirus.

Around one in four Republicans (26%) and Democrats (25%), compared to 19% of independents, agree that God rewards those who have faith with good health and will protect them from the coronavirus.

Protections and Precautions

Shutdowns and Mask Mandates

Around three in four Americans (76%) say that shutdowns, mask mandates, and other steps taken by state and local governments since the pandemic began are reasonable attempts to protect people, while 23% say that they are unreasonable attempts to control people.

Majorities of all religious groups say that these actions are reasonable attempts to protect people. More than seven in ten non-Christian religious Americans (84%), religiously unaffiliated Americans (81%), white Catholics (79%), white mainline Protestants (76%), and Protestants of color (71%) agree that these steps are reasonable. White evangelical Protestants stand out as the least likely to agree that these steps are reasonable (59%) and are more likely to say these actions are unreasonable attempts to control people (39%).[2]

Americans who attend religious services once a week or more, or once or twice a month or a few times a year, are slightly less likely than those who seldom or never attend services to say that shutdowns, mask mandates, and other government actions are reasonable attempts to protect people (70% and 73% vs. 80%).

Republicans (56%) are much less likely than independents (71%) and Democrats (94%) to say that shutdowns and mask mandates are reasonable attempts to protect people. Around four in ten Republicans (43%), compared to just 28% of independents and five percent of Democrats, say these requirements are unreasonable attempts to control people.

Americans who agree that God will protect the faithful from the coronavirus are less likely than those who do not to say that shutdowns and mask mandates are reasonable attempts to protect people (66% vs. 79%, respectively).

Mask-Wearing

More than three in four Americans (78%) say they always wear a mask when in public places. An additional 19% say they sometimes wear a mask, and just 3% say they never wear a mask.

Women are more likely than men to say they always wear a mask in public places (81% vs. 74%). White women (79%) are more likely than white men (71%) to say they always wear masks. Differences by gender are not significant for other race and ethnic groups.

White evangelical Protestants (63%) stand out as the religious group least likely to say they always wear a mask. Around eight in ten or more of nearly every other religious group say they always wear a mask, including 85% of non-Christian religious Americans, 82% of religiously unaffiliated Americans, 80% of other Christians, 79% of Black Protestants, 79% of Hispanic Catholics, 78% of white Catholics, 78% of Hispanic Protestants, and 77% of white mainline Protestants.

Much of the difference in mask-wearing rates among white evangelical Protestants is due to a large gender gap. Just 55% of white evangelical Protestant men report always wearing a mask, while 41% say they sometimes wear a mask and 3% say they never wear a mask. White evangelical Protestant women (70%) are much more likely to report always wearing a mask, while 26% say they sometimes wear a mask and 5% say they never wear a mask. The gender gap in mask-wearing is much smaller among other religious groups, but women are consistently slightly more likely than men to wear a mask.

Democrats are most likely to report always wearing a mask (90%), while just 8% say they sometimes wear a mask and 1% never wear a mask. Independents are slightly less likely to always wear a mask (78%), while 20% sometimes wear a mask and 2% never wear a mask. Around two-thirds of Republicans (65%) report always wearing a mask, while 31% sometimes wear a mask and 4% never wear a mask. There is not a significant gender gap among Republicans or Democrats, but independent women are more likely than independent men to say they always wear masks in public (82% vs. 73%).

Interestingly, those who agree that their faith in God will protect them from the coronavirus are only slightly less likely than those who disagree to say they always wear a mask (72% vs. 80%).

Inevitability of the Pandemic

Nearly seven in ten Americans (69%) say that the spread of the coronavirus in the U.S. could have been controlled better, while three in ten say an outbreak of this size was inevitable. White evangelical Protestants are the only religious group who are more likely to say that the outbreak was inevitable (55%) than to say it could have been controlled better (44%). Majorities of every other religious group say the spread could have been controlled better, including 85% of Black Protestants, 84% of non-Christian religious Americans, 78% of religiously unaffiliated Americans, 75% of Hispanic Catholics, 74% of Hispanic Protestants, 65% of white Catholics, and 57% of white mainline Protestants.

Those who frequently attend religious services are much more likely than those who attend less frequently to say the size of the outbreak was inevitable. Four in ten Americans who attend services at least once a week (40%), compared to 28% of those who attend once or twice a month or a few times a year and 25% of those who seldom or never attend services, say an outbreak of this scale was inevitable.

Six in ten Republicans (60%) say an outbreak of this size was inevitable, while 40% say it could have been controlled better. Independents and Democrats are much more likely to say that the outbreak could have been controlled better (70% and 92%, respectively) than they are to say the size of the outbreak was inevitable (29% and 7%, respectively).

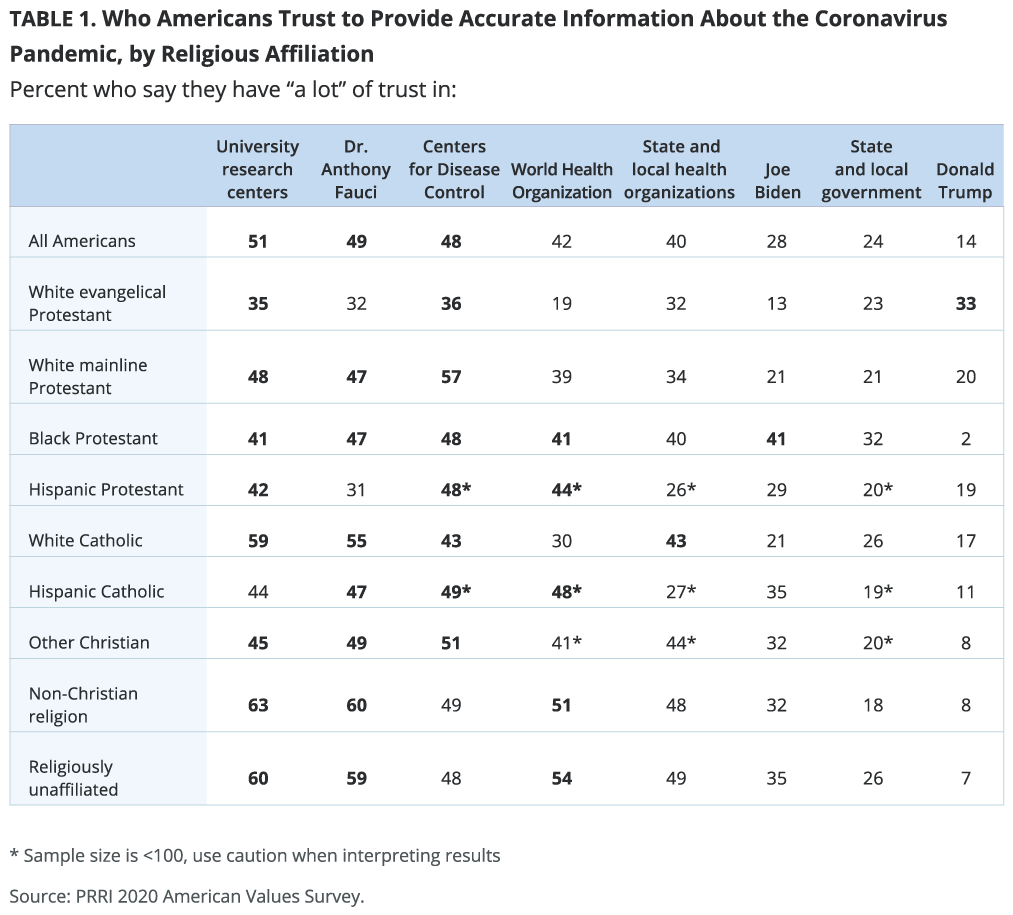

Whom Religious Americans Trust for Pandemic Information

The deluge of misinformation and disinformation about the pandemic seems to have taken a toll on Americans’ trust in sources of information across the board. Even the most trusted sources of information barely garner a majority who say they trust them “a lot.” About half of Americans say they have a lot of trust in university research centers (51%), Dr. Anthony Fauci (49%), and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (48%). About four in ten have a lot of trust in the World Health Organization (WHO) (42%) and state and local health organizations (40%). Fewer than three in ten have a lot of trust in President-elect Joe Biden (28%) or state and local governments (24%). Notably, only 14% of Americans say they hold a lot of trust in President Donald Trump to provide accurate information and advice regarding the pandemic.

The figures and organizations that different religious groups trust generally mirror the groups’ partisan leanings. White Christian groups are generally more likely to trust President Trump and somewhat less likely to trust Joe Biden or two sources Trump has called into question, Dr. Anthony Fauci and the WHO.

Religious groups are divided over how much trust they place in institutions and leaders. White evangelical Protestants, Black Protestants, Hispanic Protestants, and Hispanic Catholics who say they have a lot of trust in any of the groups or leaders tested do not reach majority levels. White evangelical Protestants are some of the least likely to place a lot of trust in most groups or people. Fewer than four in ten place a lot of trust in the CDC (36%), university research centers (35%), or Donald Trump (33%). Black Protestants are most likely to have a lot of trust in the CDC (48%), Dr. Anthony Fauci (47%), Joe Biden (41%), and the WHO (41%). Hispanic Protestants are most likely to say they have a lot of trust in the CDC (48%), the WHO (44%), and university research centers (42%). Just under half of Hispanic Catholics put a lot of trust in the CDC (49%), the WHO (48%), or Dr. Anthony Fauci (47%).

Majorities of white mainline Protestants, white Catholics, other Christians, non-Christian religious Americans, and religiously unaffiliated Americans have a lot of trust in at least one institution or figure. Around six in ten white mainline Protestants trust the CDC (57%), and about half hold a lot of trust in university research centers (48%) and Dr. Anthony Fauci (47%). White Catholics are most likely to trust university research centers (59%), Dr. Anthony Fauci (55%), and the CDC (43%), or state and local health organizations (43%). A slim majority of other Christians have a lot of trust in the CDC (51%), while just under half trust Dr. Fauci (49%) or university research centers (45%). Around six in ten non-Christian religious Americans trust university research centers (63%) or Dr. Fauci (60%), and a slim majority trust the WHO (51%). Religiously unaffiliated Americans are also most likely to trust university research centers (60%), Dr. Fauci (59%), or the WHO (54%).

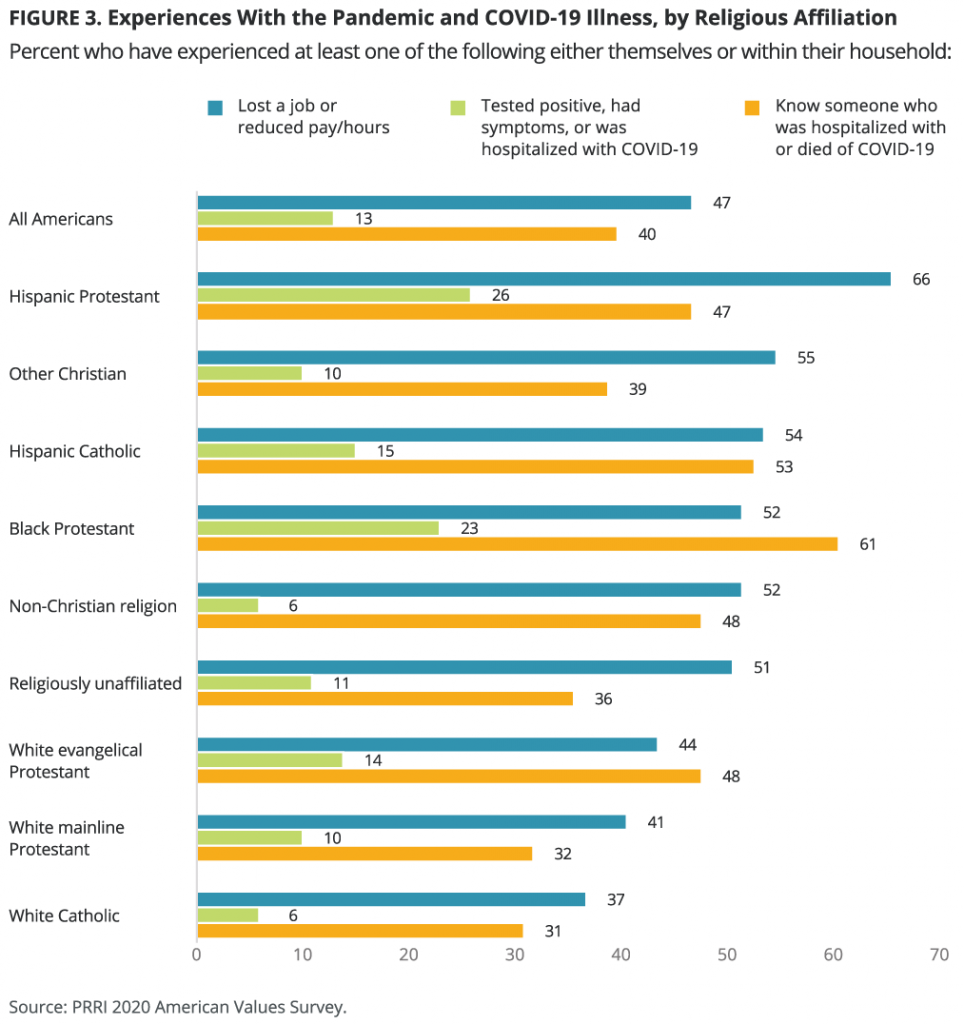

How the Pandemic Has Affected Americans

Economic Impacts of the Pandemic

Nearly four in ten Americans (38%) report that they or someone in their household has had their hours or pay cut as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. More than one in five (22%) say they or someone in their household have lost a job due to the pandemic.

When responses to both questions are combined, 37% of Americans have experienced one of the two economic hardships within their household, and an additional 12% have experienced both. A slim majority of Americans (52%) have not experienced either of these economic consequences of the pandemic themselves or within their households.

People of color are more likely than white Americans to report facing job loss, cuts in hours or pay, or both. Six in ten Hispanic Americans (60%) report one or both situations in their household, as do 55% of Asian, multiracial, or Americans of another race and 52% of Black Americans.[3]

By contrast, only 44% of white Americans report facing job losses or pay cuts in their households.

Among religious groups, those most likely to report one or both of these situations are Hispanic Protestants (66%), other Christians not included in any other category (55%), Hispanic Catholics (54%), Black Protestants (52%), those who belong to non-Christian religions (52%), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (51%). White Christian groups are less likely to have faced these pandemic-induced economic struggles, although around four in ten white evangelical Protestants (44%), white mainline Protestants (41%), and white Catholics (37%) report facing one or both of these situations. Nearly one in four Hispanic Protestants (23%) report experiencing both job loss and cuts in hours or pay in their households, which is almost twice as much as any other group.

Republicans are less likely than independents to report facing one or both situations (43% vs. 51%), but neither group differs significantly from Democrats (48%).

Not surprisingly, those who report their financial situation is in excellent shape (29%) are less likely than those who report it is in good shape (42%), fair shape (54%), or poor shape (65%) to report facing job loss, cuts in hours or pay, or both.

Personal Household Experiences With COVID-19 Illness

When this survey was fielded, 6% of Americans reported that they or someone in their household had tested positive for COVID-19, 10% reported that they or someone in their household had gotten sick with COVID-19 symptoms, and 2% reported that they or someone in their household had been hospitalized with COVID-19. When responses are combined, 14% of Americans have experienced at least one of these COVID-19 situations in their household.

Black and Hispanic Americans (19% and 18%, respectively) are approximately twice as likely as white (10%) and Asian, multiracial, or Americans of another race (10%) to report experiencing at least one of these situations in their households.

Hispanic Protestants (26%) and Black Protestants (23%) are the most likely religious groups to face at least one of these COVID-19 illness situations in their household. Fewer Hispanic Catholics (15%), white evangelical Protestants (14%), religiously unaffiliated Americans (11%), other Christians not included in any other category (10%), and white mainline Protestants (10%) report experiencing one or more COVID-19 illness situations. Few white Catholics (6%) and non-Christian religious Americans (6%) report one or more of these experiences.

Knowing People Who Were Hospitalized With or Died of COVID-19

At the time of the survey, 34% of Americans reported they knew someone who had been hospitalized with COVID-19, and 22% reported knowing someone who had died from it. Combined, 40% of Americans know someone who has been hospitalized with or died of COVID-19.

Overall, Black (58%), Hispanic (50%), and Asian, multiracial, or Americans of another race (46%) are more likely than white Americans (36%) to know someone who was hospitalized with or died of COVID-19.

More than six in ten Black Protestants (61%) know someone who has either been hospitalized with or died of COVID-19. This is notably higher than among any other group, including Hispanic Catholics (53%), white evangelical Protestants (48%), non-Christian religious Americans (48%), and Hispanic Protestants (47%). Less than four in ten other Christians not included in any other category (39%), religiously unaffiliated Americans (36%), white mainline Protestants (32%), and white Catholics (31%) know someone who has either been hospitalized or died of COVID-19, or both.

Republicans are significantly less likely than independents or Democrats to report knowing someone who has been hospitalized or died of COVID-19 (36% vs. 42% and 46%, respectively).

Those who do not know anyone who has been hospitalized or died of COVID-19 (55%) are less likely than those who know someone who has been hospitalized or who has died (63%) to say that the coronavirus pandemic is a critical issue (55%). Those who know someone in both cases are the most likely to say the pandemic is a critical issue (76%).

Estimating COVID-19 Exposure for Religious Subgroups in the United States

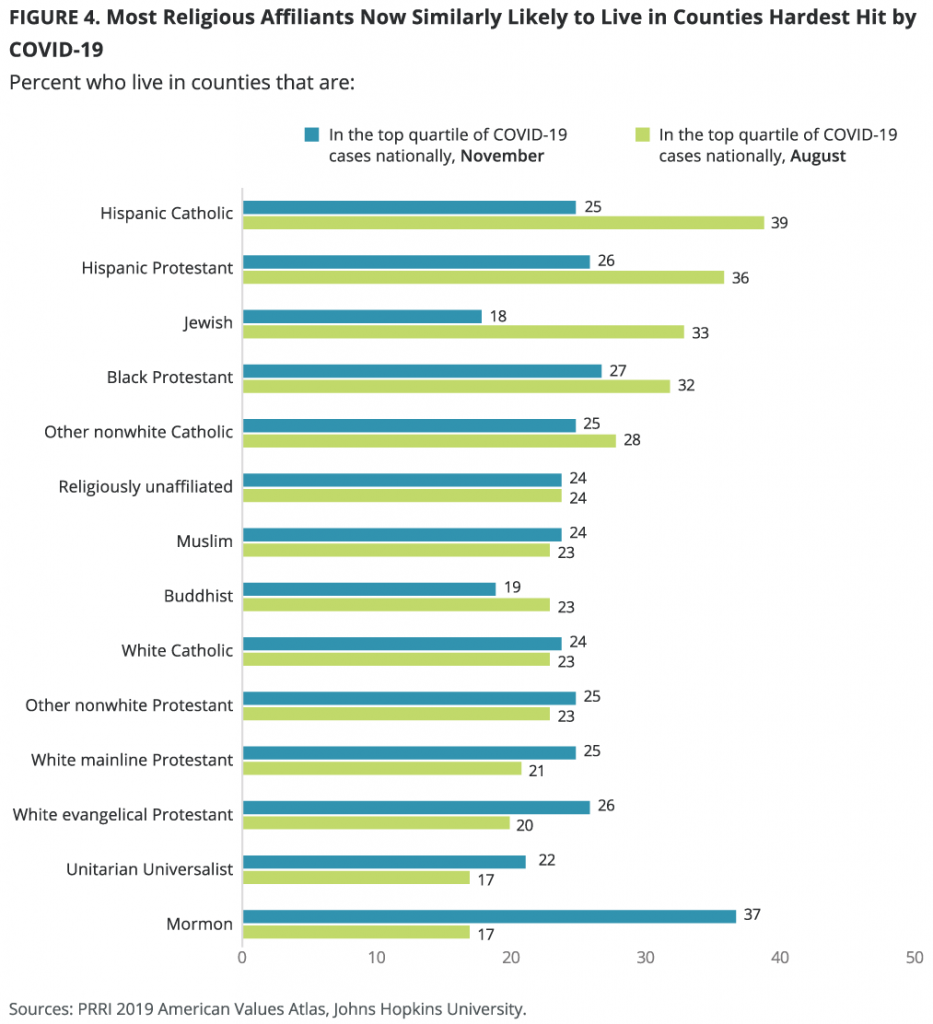

In August, PRRI estimated how the pandemic had affected religious communities based on where adherents live.[4]

At that time, the novel coronavirus and the illness it causes, COVID-19, had affected communities in the United States at vastly different rates and degrees of severity. Population density and differing state and local government actions to combat the spread of the pandemic were producing vastly uneven outcomes. Not all religious groups had been affected in the same way, because in the U.S., particular religious groups are clustered in specific regions of the country; some are more likely to serve rural communities while others are rooted in larger cities. In addition, religious denominations in the U.S. remain highly segregated by race and ethnicity, and the pandemic has disproportionately impacted African American and Hispanic communities and certain areas of the country.

Not surprisingly, the late summer analysis showed that Hispanic Christian, Black Christian, and non-Christian religious groups were more likely to live in areas hardest hit by COVID-19. This pattern was driven in part by the sizable portions of those groups living in urban areas of the country, which have been more heavily impacted by the pandemic. An update of this analysis, however, shows that those differences have leveled off as the pandemic has spread and rates of infection have increased across the country. As a result, most religious groups are now equally likely to live in the counties hardest hit by the pandemic. Figure 5 shows the proportion of each religious group that lives in counties in the top quartile (75th–100th percentiles) of cases per 100,000 residents in the U.S. in August and November. [5]

The largest shift has occurred among Mormons, who were among the least likely to live in highly affected counties in August (17%) but are now the most likely to live in counties in the top quartile of cases nationally (37%). In the other direction, areas, where Jewish Americans, Hispanic Catholics, and Hispanic Protestants live, have become substantially less likely to be in the top quartile of cases. More than one-third of Hispanic Catholics (39%) and Hispanic Protestants (36%) lived in counties that were hot spots in August, but now those areas are down to average levels nationally (25% and 26%, respectively). Similarly, one-third of Jewish Americans lived in counties that were in the top quartile of COVID-19 cases in August, compared to 18% in November. About one-quarter of white Christian groups live in counties that are in the top quartile of COVID-19 cases, up slightly from August.

Survey Methodology and Footnotes

[1]The survey was fielded in September 2020, before cases began rising in October and November.

[2]Because of a split sample on this question, other religious groups are too small to examine. This includes Black Protestants, Hispanic Protestants, Hispanic Catholics, and other Christians.

[3]Sample sizes are too small to report Asian, multiracial, or another race groups separately.

[4]https://www.prri.org/research/estimating-covid-19-exposure-for-religious-subgroups-in-the-united-states/

[5]Directly measuring how religious communities have been affected by the pandemic is virtually impossible, as there is no source of COVID-19 data by religious affiliation. However, the geographic location of U.S. residents who affiliate with different religious groups can serve as a proxy indicator of how much COVID-19 exposure on average members of a religious group have experienced. In this report, we draw on two primary data sources: PRRI’s 2019 American Values Atlas, which provides nationally representative data on the religious affiliation of more than 53,000 U.S. residents, including their county-level geographic location; and county-level case data from the COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University, as of November 22, 2020, which provides the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths each county in the U.S. has reported since February. To estimate COVID-19 exposure by religious affiliation, we merged these two data sets, aggregated religious affiliation and COVID-19 cases at the county level, and computed average exposure for each religious subgroup. Importantly, this means that COVID-19 exposure in these religious groups is inherently tied to their geographic location at the county level. It does not mean that each member of the religious group has an identical experience; rather, it creates an aggregate picture of the overall religious group’s experience based on where its adherents live.