At this point, there doesn’t seem to be much about Mitt Romney’s Mormon background that hasn’t been exhaustively picked over by the media. The same is true to a lesser extent of Rick Perry and Michele Bachmann; the two former Republican front-runners sparked controversy late in the summer for their alleged links to Dominionism, an extreme Christian theological movement. Bachmann was profiled in The New York Times and The New Yorker, while Perry continues to be embroiled in the commotion over evangelical pastor Robert Jeffress’ claims that Mormonism is not a Christian faith.

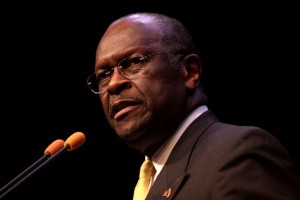

But with Herman Cain now making a legitimate claim for “front runner” status, what can we say about his religious beliefs and their impact on his political views? Given that a majority of Americans say they want a candidate with strong religious beliefs it would seem like an obvious question, but Cain seems to be the only one interested in discussing his Christian faith. Last week, he announced that he would challenge Perry for white evangelical primary voters, touting his own Christian conservative roots.

Religion figured more prominently early in Cain’s campaign. In a March interview with CBN’s David Brody, he said:

I’m a Baptist preacher. A lot of people don’t know that. My parents joined Antioch Baptist Church North in Atlanta in the mid 40s when they moved to Atlanta when I was 2 years old. That was the church I grew up in. That was the church I joined at 10 years of age. I’ve been in the church all my life. When I moved around in my corporate career, I always stayed involved in the church.

Antioch Baptist Church North is, according to John Blake, a former member, significantly more liberal than Cain. The church’s senior minister, the Rev. C.M. Alexander, says that he doesn’t talk politics with Cain. And Cain’s conservative philosophy – that “if you don’t have a job and you’re not rich, blame yourself” – does not exactly fall into line with the pastor’s views on social justice. Alexander doesn’t, according to a colleague, “talk about pulling yourself up by your bootstraps.” Rather, he emphasizes “providing bootstraps.”

Last April, a survey from Public Religion Research Institute found that minority Christians (a group comprised primarily of black and Latino Protestants) feel more strongly than other religious denominations that capitalism and the free market are at odds with Christian values (56% of minority Christians agree, compared to 43% of white mainline Protestants and Catholics). Similarly, minority Christians want their pastors to speak out about economic issues. Seventy-one percent of minority Christians said that it was important for their religious leaders to speak out about raising the minimum wage, compared to 41% of white evangelical Protestants and white mainline Protestants.

According to their friends, Rev. Alexander respects Cain despite their differences on fundamental political issues. And others who have seen Cain in action at Antioch say that he is comfortable and confident when talking about his faith, despite the fact that it hasn’t played much of a role in his campaign of late. This raises two important questions: Will Cain be successful in his attempt to compete with Rick Perry for evangelical Christian primary voters? And will black Protestants be as willing as his pastor to separate Cain’s faith from his political philosophy?