Overview of the Study

The religious landscape of the United States has changed dramatically in the past few decades as the country has become more demographically diverse, more Americans than ever have disaffiliated with organized religion, and religious leaders have faced a cultural milieu increasingly polarized along racial and political lines. Churches are also transitioning back to in-person services following the COVID-19 pandemic and dealing with ongoing ripple effects from other major events, including national protests for racial justice, a divisive 2020 presidential election that resulted in a deadly insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, and renewed state legislative battles over reproductive and LGBTQ rights.

This new survey examines the religious behaviors of Americans amid this uncertain cultural and political landscape. In addition to highlighting religious affiliation trends, we consider the importance of religion to Americans and look at how often they attend church and engage in religious activities such as prayer. We also look at trends in religious “switching”—leaving one religion for another—and consider the reasons Americans do so.

We also analyze the political context that congregations face today. We ask regular churchgoers how often they discuss political and cultural issues in their churches, how well their churches address those issues, and the extent to which partisan divides are apparent in their congregations.

The Diversifying American Religious Landscape

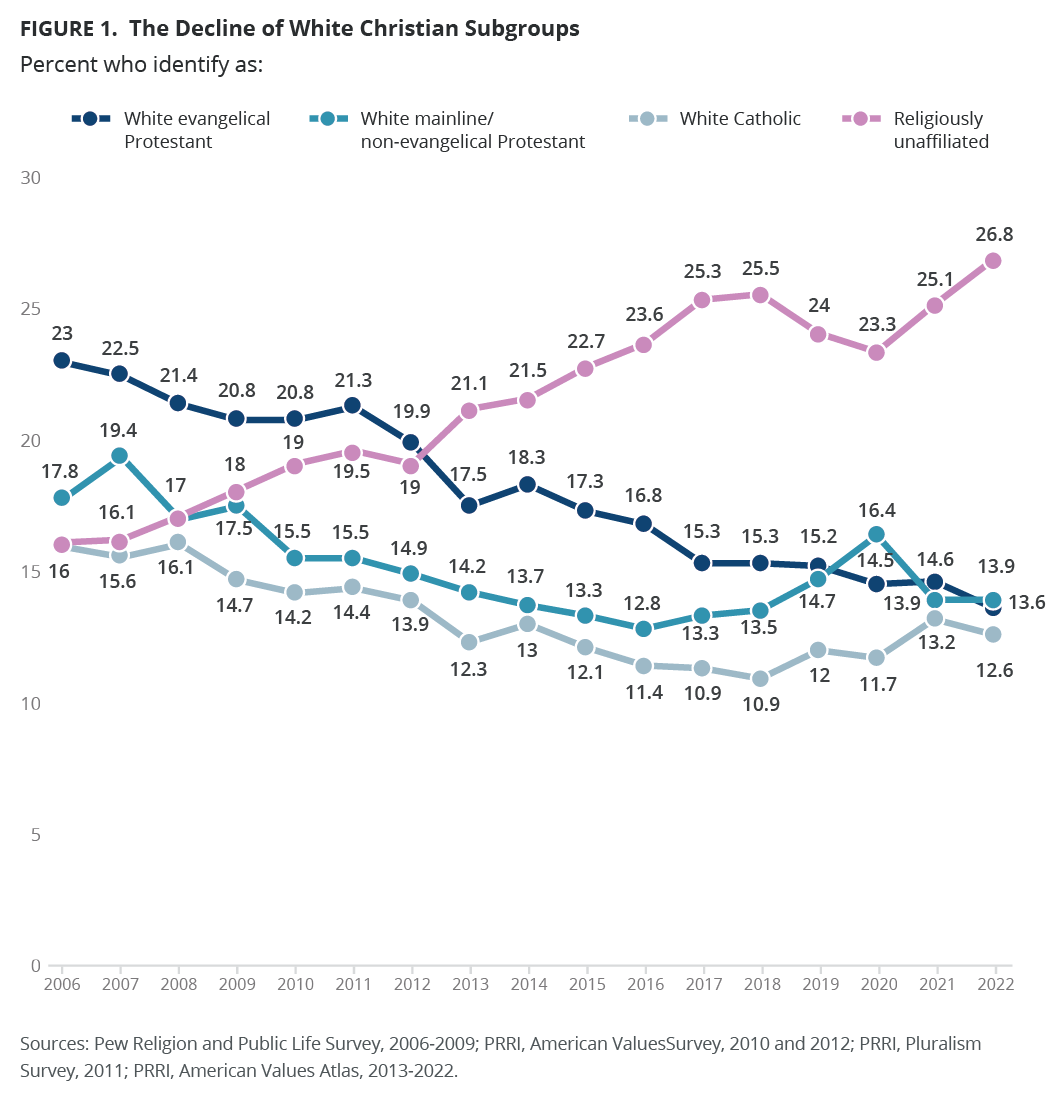

Despite a diversifying religious landscape, most Americans are still Christian. PRRI’s 2022 American Values Atlas shows that the proportion of white Christians in the country is 42% and has remained relatively constant since 2018 (42%) after a long decline from 72% in 1990 and 54% as recently as 2006. Included in the white Christian portion of the U.S. adult population are 14% of Americans who are white evangelical Protestant (down from 23% in 2006), 14% who are white mainline/non-evangelical Protestant (down from 18% in 2006), 13% who are white Catholic (down from 16% in 2006), and small proportions of white Latter-day Saints, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Orthodox Christians.

Christians of color make up 25% of the country. This group includes Christians who identify as Black, Hispanic, Asian American or Pacific Islander, Native American, multiracial, or any other race or ethnicity. The proportion of Christians of color as part of the United States’ population remains essentially unchanged from the preceding few years.

The proportion of those who are religiously unaffiliated has risen to 27% from 16% in 2006.

The remaining 6% of Americans belonging to other religions has remained steady over the past few years. This group includes those who are Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, or Unitarian Universalist, or belong to any other world religion.

A significant minority of Americans practice more than one religion. Nearly one in five Americans (19%) say they consider themselves “a follower of the teachings or practices of more than one religion.” Adherents of non-Christian religions (26%), Hispanic Catholics (24%), and white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (24%) are among those most likely to be multi-religious, while white evangelical Protestants (18%) and Protestants of color (16%) are the least likely to follow more than one religion’s teachings.

Importance of Religion

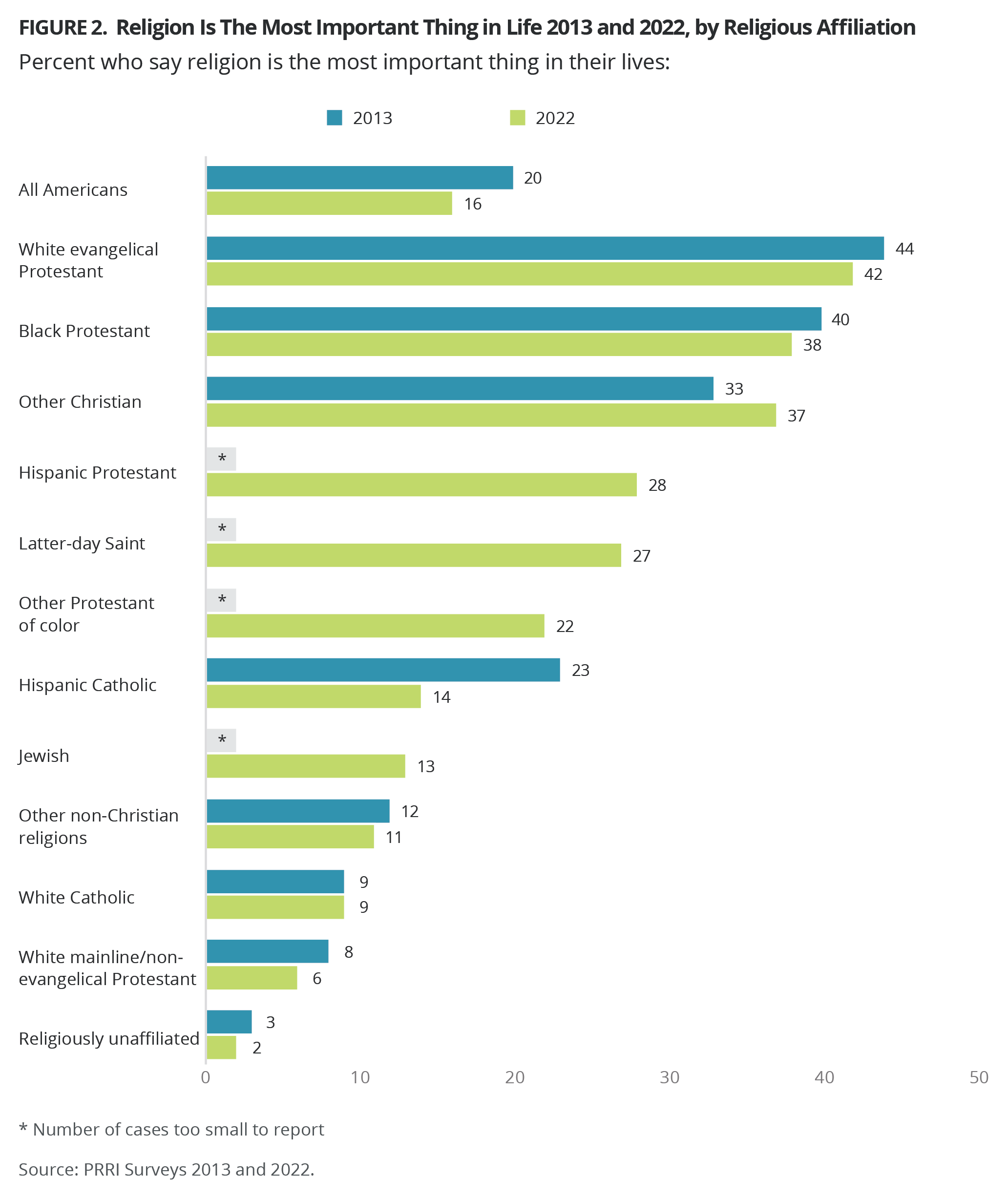

Religion is less important for Americans today than it was a decade ago. Today, 16% of Americans say that religion is the most important thing in their life, 36% say religion is one among many important things, 18% say religion is not as important as other things, and 29% say religion is not important to them. In 2013, Americans were more likely to say that religion was either the most important thing in their life (20%) or one among many important things (43%), while 15% said that religion was not as important as other things and 19% said religion was not important.

In the 2022 survey, white evangelical Protestants (42%), Black Protestants (38%), and other Christians (37%) are groups the most likely to say that religion is the most important thing in their lives, compared with 28% of Hispanic Protestants, 27% of Latter-day Saints, and 22% of other Protestants of color.[1] Lower proportions of Hispanic Catholics (14%), Jewish Americans (13%), other non-Christians (11%), white Catholics (9%), white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (6%), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (2%) say religion is the most important thing in their lives.[2] Catholics in particular have seen a significant shift in the number who say religion is not important in their lives. White Catholics (16%) are twice as likely in 2022 as they were in 2013 to say religion is not important (16% vs. 7%), and this gap is larger among Hispanic Catholics (13% vs. 2%). Not surprisingly, 78% of religiously unaffiliated Americans say that religion is not important in their lives, up from 73% in 2013.

Religious Attendance

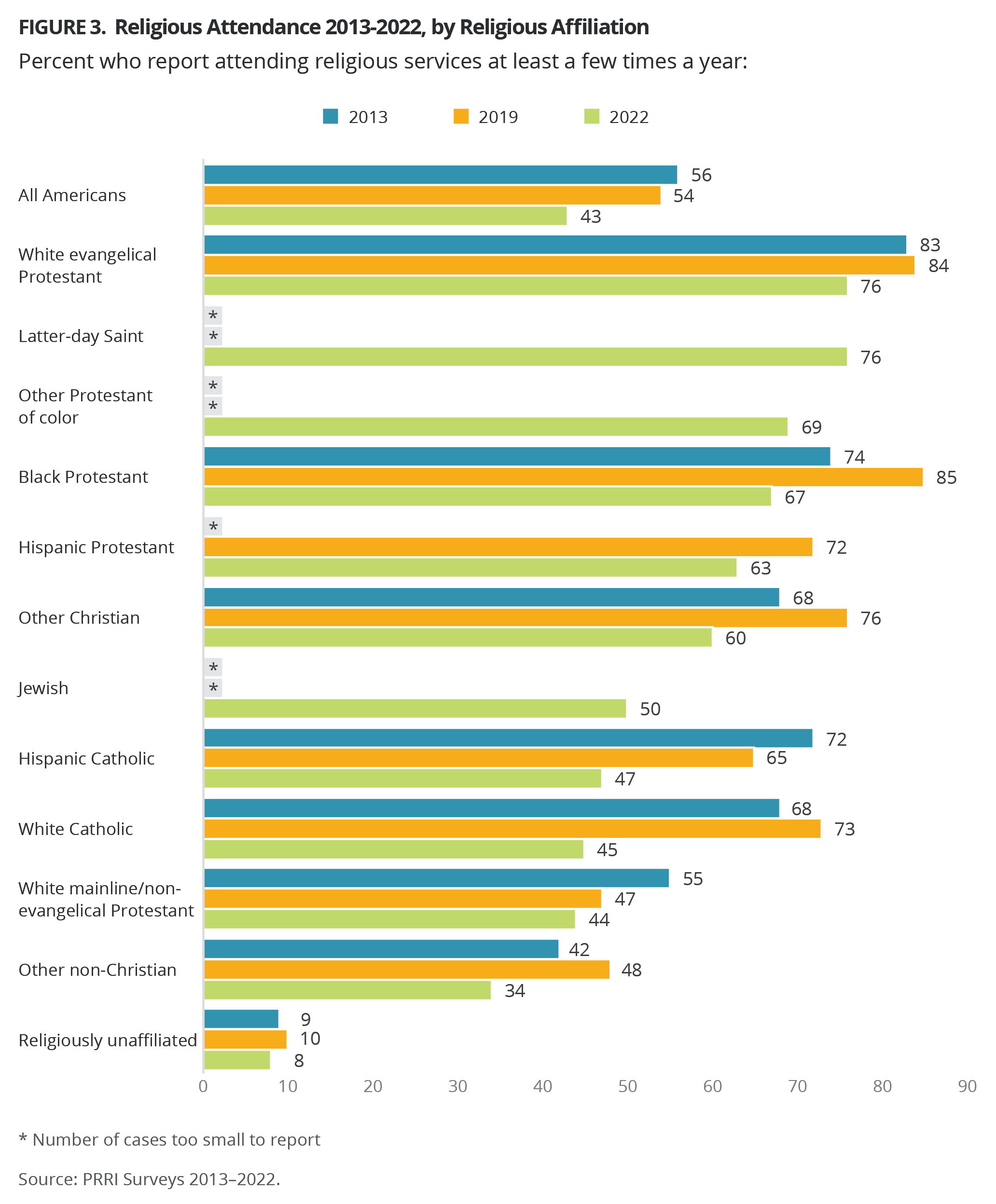

In 2022, more than four in ten Americans say they attend religious services, aside from weddings and funerals, at least a few times a year, including 7% who say they attend more than once a week, 16% who say they go once a week, 7% who go once or twice a month, and 13% who go a few times a year. Most Americans say they seldom (28%) or never (29%) attended religious services. These percentages are lower than those registered in both 2019 and in 2013, when most Americans said they attended religious services more than once a week (9% and 11%), once a week (19% and 20%), once or twice a month (both 9%) or a few times a year (17% and 16%), compared with about four in ten who said they attended seldom (21% and 22%) or never (24% and 21%). The COVID-19 pandemic is most likely a factor in these shifts.

White evangelical Protestants (76%, down from 84% in 2019 and 83% in 2013) and Latter-day Saints (76%) are the most likely to say they attend religious services at least a few times a year, followed by other Protestants of color (69%), Black Protestants (67%, down from 85% in 2019 and 74% in 2013), Hispanic Protestants (63%, down from 72% in 2019), and other Christians (60%, down from 76% in 2019 and 68% in 2013).[3] Half or less than half of Jewish Americans (50%), Hispanic Catholics (47%, down from 65% in 2019 and 72% in 2013), white Catholics (45%, down from 73% in 2019 and 68% in 2013), and white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (44%, slightly down from 47% in 2019 and 55% in 2013), as well as one-third of other non-Christians (34%, down from 48% in 2019 and 42% in 2013), and 8% of religiously unaffiliated Americans (similar to 10% in 2019 and 9% in 2013) report the same.[4]

Religious Participation

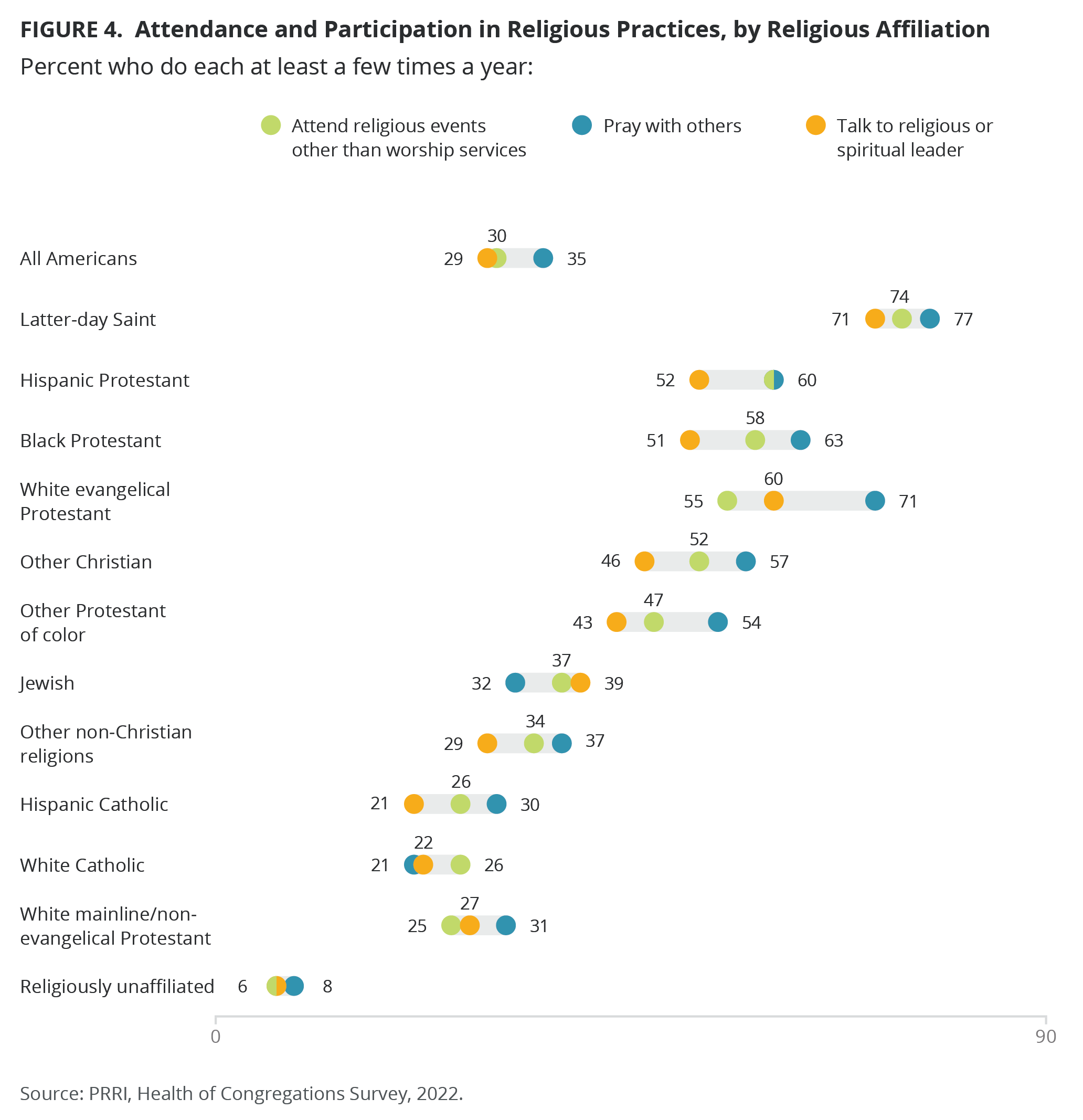

More than one-third of Americans (35%) say they pray with other people at least a few times a year, while three in ten say they attend religious events other than worship services at least a few times a year (30%) or talk to religious or spiritual leaders at least a few times a year (29%).

More than seven in ten Latter-day Saints say they pray with others (77%), attend non-worship religious events (74%), or talk to religious leaders (71%) at least a few times a year. Majorities of white evangelical Protestants (71%, 55%, 60%, respectively, for each activity), Black Protestants (63%, 58%, 51%, respectively), and Hispanic Protestants (60%, 60%, 52%) also report doing these three activities at least a few times a year.

Meanwhile, though majorities of other Christians and other Protestants of color say they pray with others (57% and 54%, respectively), only a slim majority of other Christians and less than half of other Protestants of color say they attend religious events other than worship services (52% and 47%, respectively). Fewer than half of those in each group say they talk to religious or spiritual leaders (46% and 43%, respectively).

Participation is lower among Jewish Americans, among whom 32% pray with others, 37% attend non-worship religious events, and 39% talk to religious leaders at least a few times per year. Other non-Christians report similarly low participation in these three activities (37%, 34%, 29%, respectively). And participation in these activities is below one-third among white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (31%, 25%, 27%, respectively for each activity), Hispanic Catholics (30%, 26%, 21%), and white Catholics (21%, 26%, 22%). Religiously unaffiliated Americans are far less likely to participate in any of these activities (8%, 6%, 6%, respectively).

Civic Participation

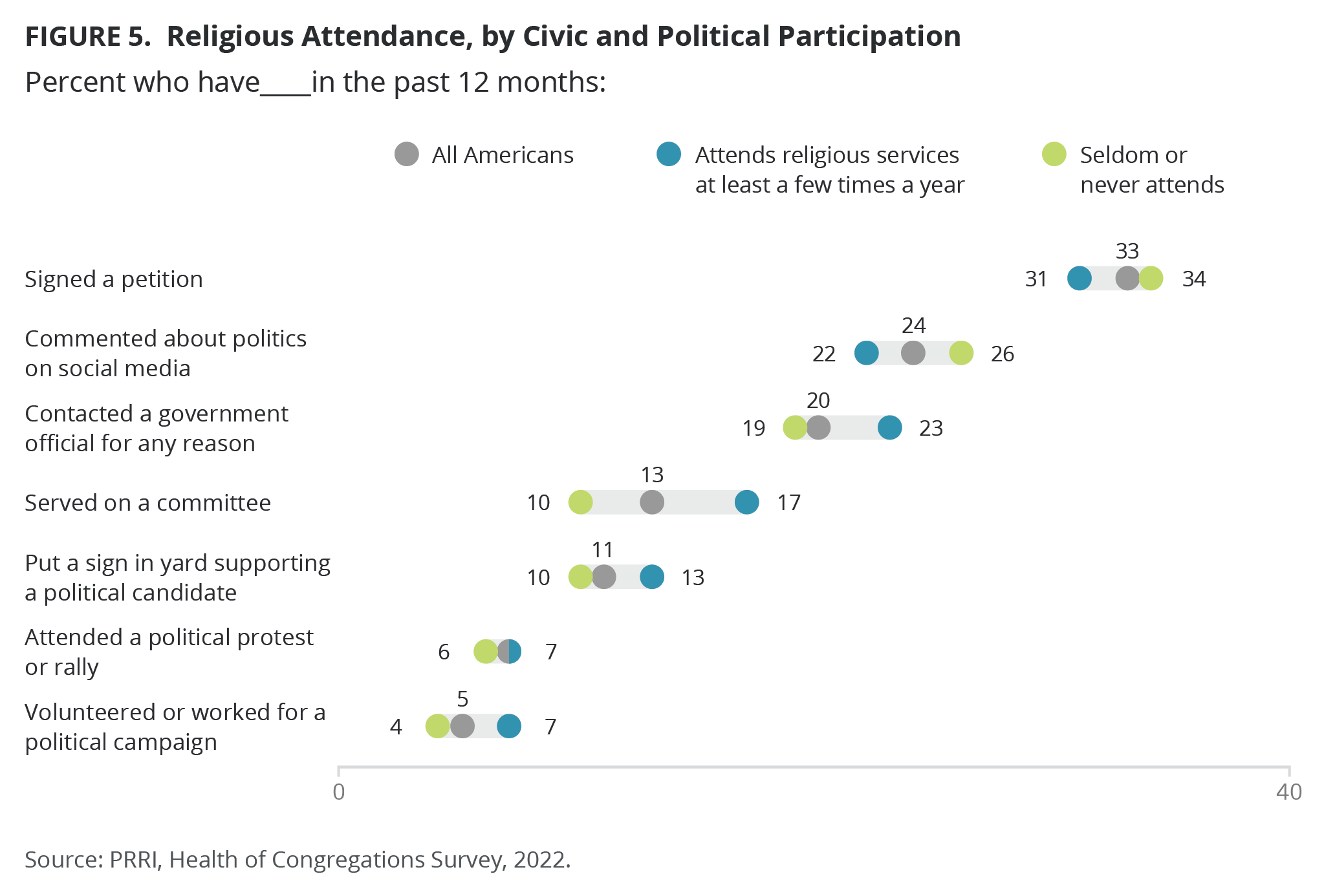

When asked about their civic and political participation in the past year, one-third of Americans (33%) said they signed a petition either in person or online; 24% said they commented about politics on a message board or internet site, including social media; 20% said they contacted a government official; 13% said they served on a committee for a civic, nonprofit, or community organization or event; 11% said they put a sign in their yard or a bumper sticker on their car supporting a candidate for political office; 7% said they attended a political protest or rally; and just 5% said they volunteered or worked for a political campaign.

Americans who attend church at least a few times a year are notably more likely than those who seldom or never attend church to have contacted a government official (23% vs. 19%), served on a committee (17% vs. 10%), put up a sign supporting a political candidate (13% vs. 10%), or volunteered for a political campaign (7% vs. 4%). By contrast, Americans who attend church more frequently are less likely than those who seldom or never attend to have commented about politics (22% vs. 26%).

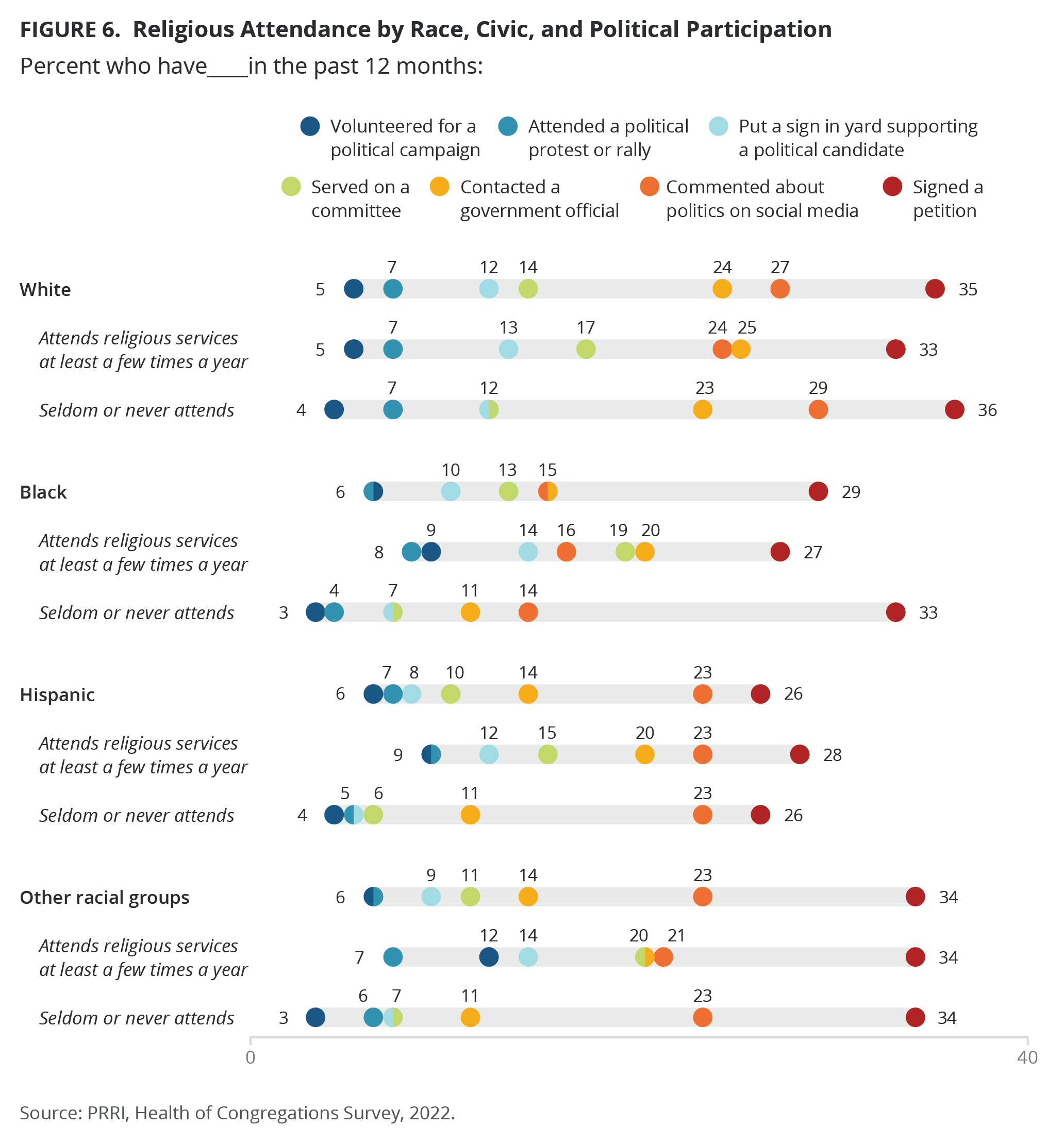

White Americans participate in civic and political activities more than nonwhite Americans do. For example, white Americans are more likely to have signed a petition (35%) or contacted a government official (24%) than both Black Americans (29% and 15%, respectively) and Hispanic Americans (26% and 14%, respectively). White Americans are also more likely than Black Americans to have commented about politics (27% vs. 15%) and are more likely than Hispanic Americans to have served on a committee (14% vs. 10%) or put a sign in their yard supporting a candidate (12% vs 8%).

When examining religious attendance together with race and civic and political participation, white churchgoers are notably more likely than white non-churchgoers to have served on a committee (17% vs. 12%), but are less likely to have commented about politics (24% vs. 29%). Black churchgoers are more likely than Black non-churchgoers to have contacted a government official (20% vs. 11%), served on a committee (19% vs. 7%), or volunteered for a political campaign (9% vs. 3%). Hispanic churchgoers are also more likely than Hispanic non-churchgoers to have contacted a government official (20% vs. 11%), served on a committee (15% vs. 6%), or put up a sign supporting a candidate (12% vs. 5%). Churchgoers of other racial groups are more likely than non-churchgoers of other races to have served on a committee (20% vs. 7%) or volunteered for a political campaign (12% vs. 3%).[5]

Fluidity in the American Religious Landscape

Religious Switching

In 2022, about one in four Americans (24%) say they were previously a follower or practitioner of a different religious tradition or denomination than the one they belong to now, up from 16% in 2021.[6]

People who are currently members of other non-Christian religions (38%) or religiously unaffiliated (37%) are the most likely to say that they were previously a follower or practitioner of a different religious tradition, followed by about one in four other Protestants of color (28%), white evangelical Protestants (25%), and Hispanic Protestants (24%). In addition, 22% each of other Christians, white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, and Latter-day Saints also say they were previously a practitioner or follower of a different religious tradition or denomination. Jewish Americans (15%), Black Protestants (15%), Hispanic Catholics (11%) and white Catholics (10%) are the least likely to say they were previously a follower or practitioner of a different religious tradition.

Religious Affiliation Movements

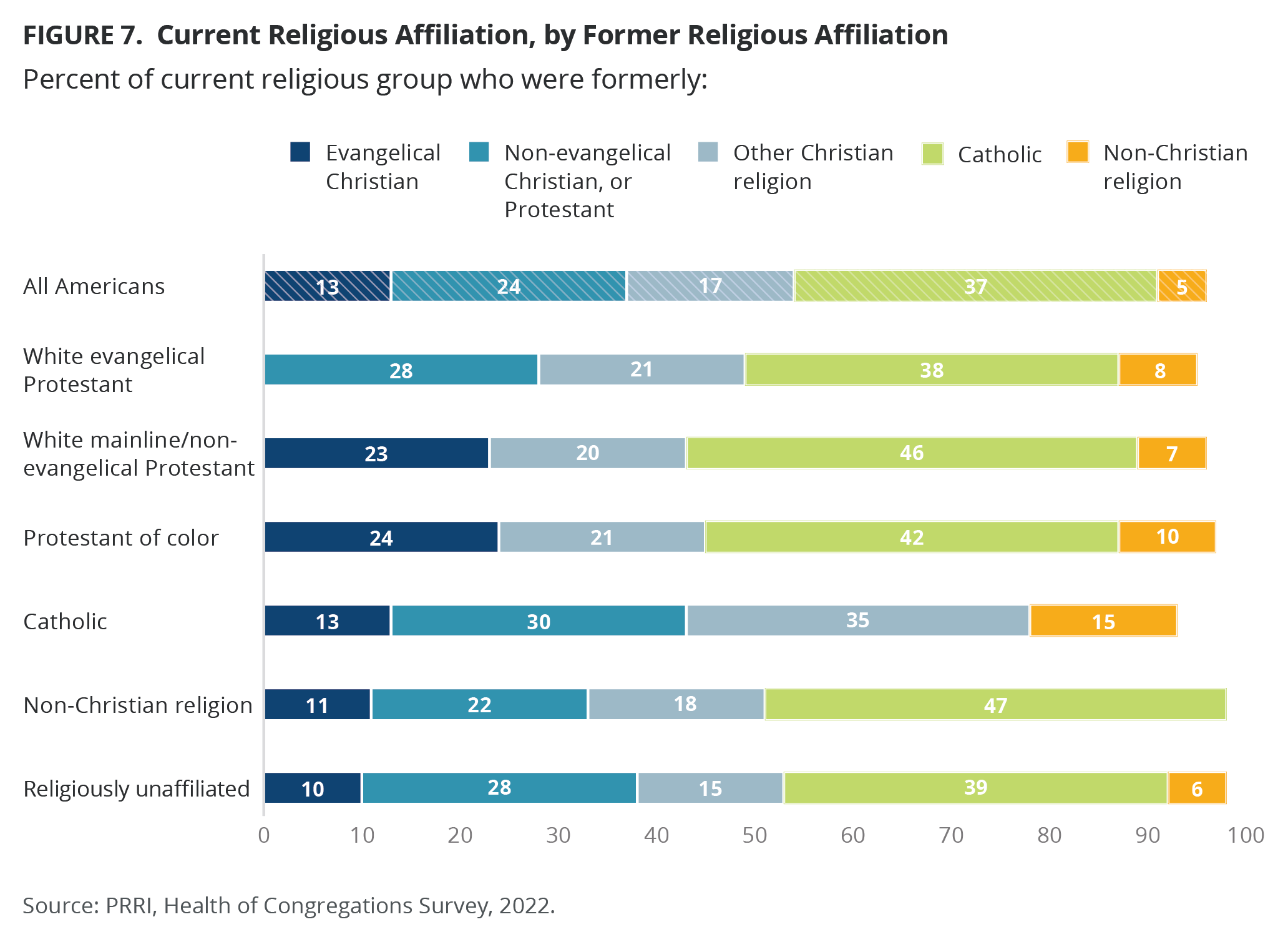

Among Americans who left a religious tradition, 37% say they were formerly Catholic, 24% were non-evangelical Christian or Protestant, 17% belonged to another Christian tradition, 13% were evangelical Christians, and 5% were members of non-Christian religions.[7]

Among those who currently identify as white evangelical Protestants and who said they had changed their religious affiliation, 38% were previously Catholic, 28% were non-evangelical Christians, 21% belonged to other Christian groups, and 8% were non-Christian.[8] Among those who currently identify as white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, 46% were previously Catholic, 23% were evangelical Christians, 20% were part of other Christian traditions, and 7% were non-Christians. Among those who currently identify as Protestants of color, 42% were Catholic, 24% were evangelical Christians, 21% belonged to other Christian groups, and 10% were non-Christians. Among those who currently are Catholic, 35% previously followed other Christian traditions, 30% were non-evangelical Protestants, 15% were non-Christians, and 13% were evangelical Christians.[9]

Among those who currently identify with a non-Christian religion, 47% were previously Catholic, 22% were non-evangelical Christians, 18% belonged to another Christian tradition, and 11% were evangelical Christians. Among those who currently are religiously unaffiliated, 39% were Catholic, 28% were non-evangelical Christians, 15% were another Christian religion, 10% were evangelical Christians, and 6% were non-Christians.

The vast majority of people who report changing religious tradition or denomination were young when they made the switch: 27% say they were younger than 18, 44% were between 18 and 29, 21% were between 30 and 49, and just 7% were age 50 or older.

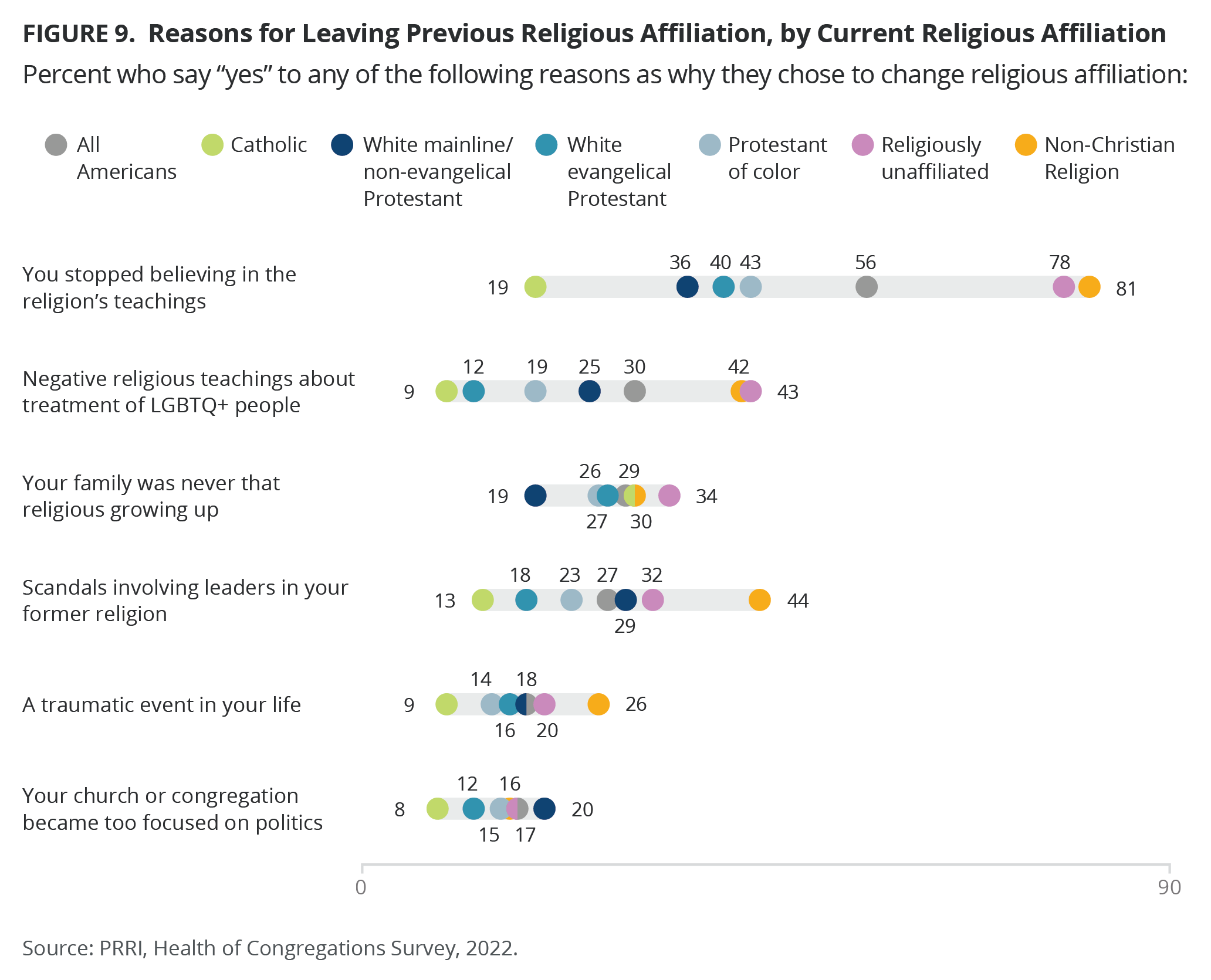

Reasons Switchers No longer Identify With Previous Religion

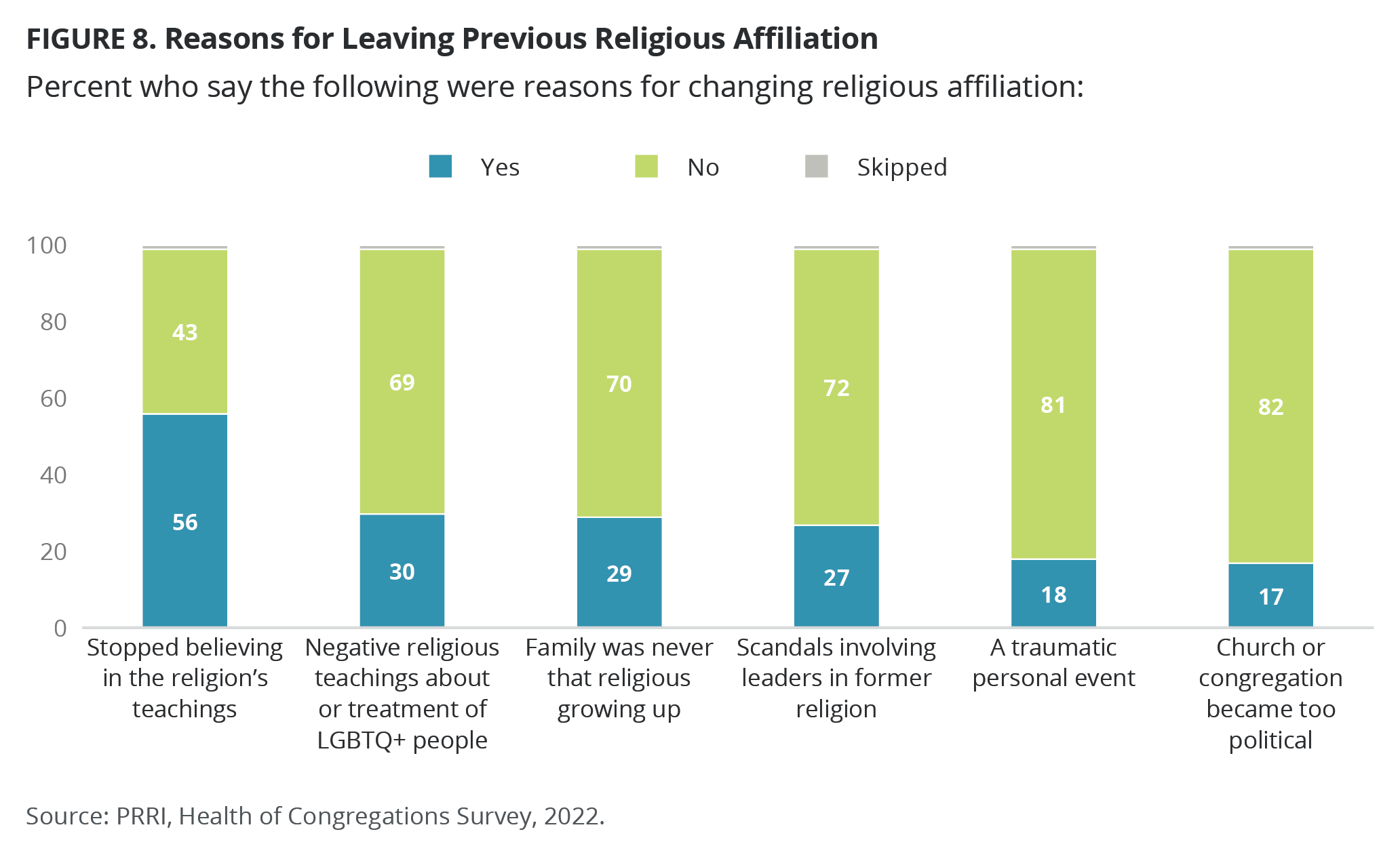

Reasons for switching religious tradition or denomination vary, but a majority of those who changed (56%) say they stopped believing in the religion’s teachings. Another 30% indicate they were turned off by the religion’s negative teachings about or treatment of LGBTQ people, 29% say their family was never that religious growing up, 27% say they were disillusioned by scandals involving leaders in their former religion, 18% point to a traumatic event in their lives, and 17% say their church became too focused on politics.[10] These reasons for leaving are largely consistent with the last time PRRI asked this question, in 2016.

Large majorities of religiously unaffiliated (78%) and non-Christian (81%) switchers say they no longer identify with their previous religion because they stopped believing in its teachings. Around four in ten Protestants of color (43%) who switched did so based on no longer believing, as did 40% of white evangelical Protestants, 36% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, and 19% of Catholics. Negative teachings about LGBTQ people were a reason to change religions or denominations for about four in ten religiously unaffiliated (43%) and non-Christian (42%) switchers.[11]

Thinking About Leaving Current Religion

Only 16% of Americans say they are thinking about leaving their current religious tradition or denomination. About two in ten Latter-day Saints (24%), other Protestants of color (20%), white Catholics (20%), white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (18%), and other Christians (17%) say they are thinking about leaving their religious tradition, compared with 15% of white evangelical Protestants, 14% of Hispanic Protestants, 13% of Hispanic Catholics, 11% of Black Protestants, and 10% of both Jewish Americans and members of other non-Christian religions.

Health of Congregations: A View from Christian Churchgoers

The remainder of this report focuses on Christians who attend church services at least a few times a year, in order to shed light on the issues facing churches and congregations in the wake of the pandemic and the past few years of social and political upheaval.

The Churches Americans Attend

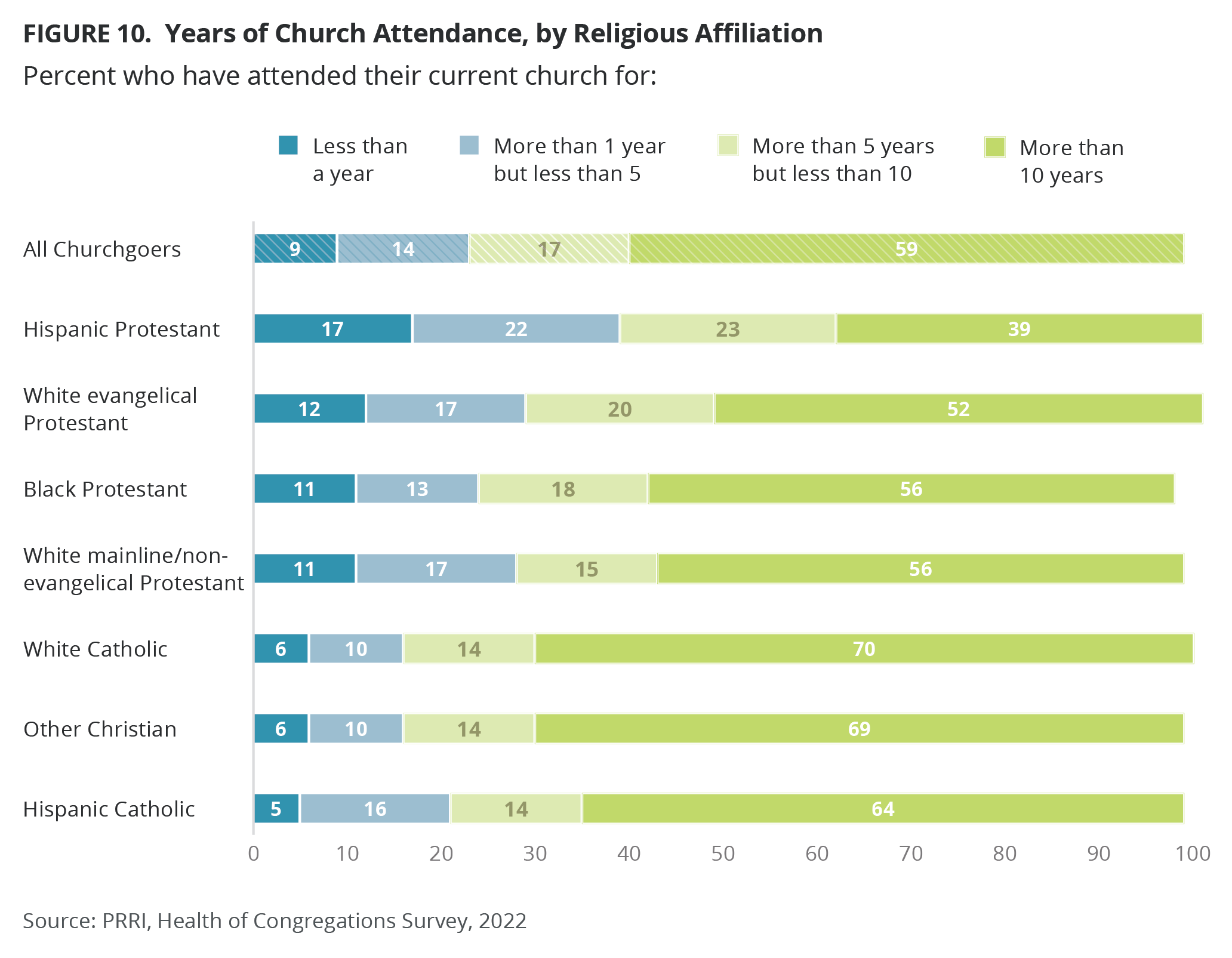

Years of attendance

Among those who attend services at least a few times a year, about one in ten churchgoers (9%) say that they have been attending their current church for less than a year, 14% say they have attended for more than one year but less than five, 17% have attended for more than five years but less than 10, and the majority (59%) say they have attended the same church for more than 10 years.

Most churchgoers across Christian traditions have attended their current church for more than 10 years. This includes 70% of white Catholics, 69% of other Christians, 64% of Hispanic Catholics, 56% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, 56% of Black Protestants, 52% of white evangelical Protestants. Among Hispanic Protestants, 39% have attended the same church for more than ten years.[12]

Senior churchgoers (71%) and those ages 50 to 64 (65%) are the most likely to say they have attended their current church more than 5 years or more than 10 years, compared with 50% of churchgoers ages 30 to 49 and 43% of young churchgoers ages 18–29.

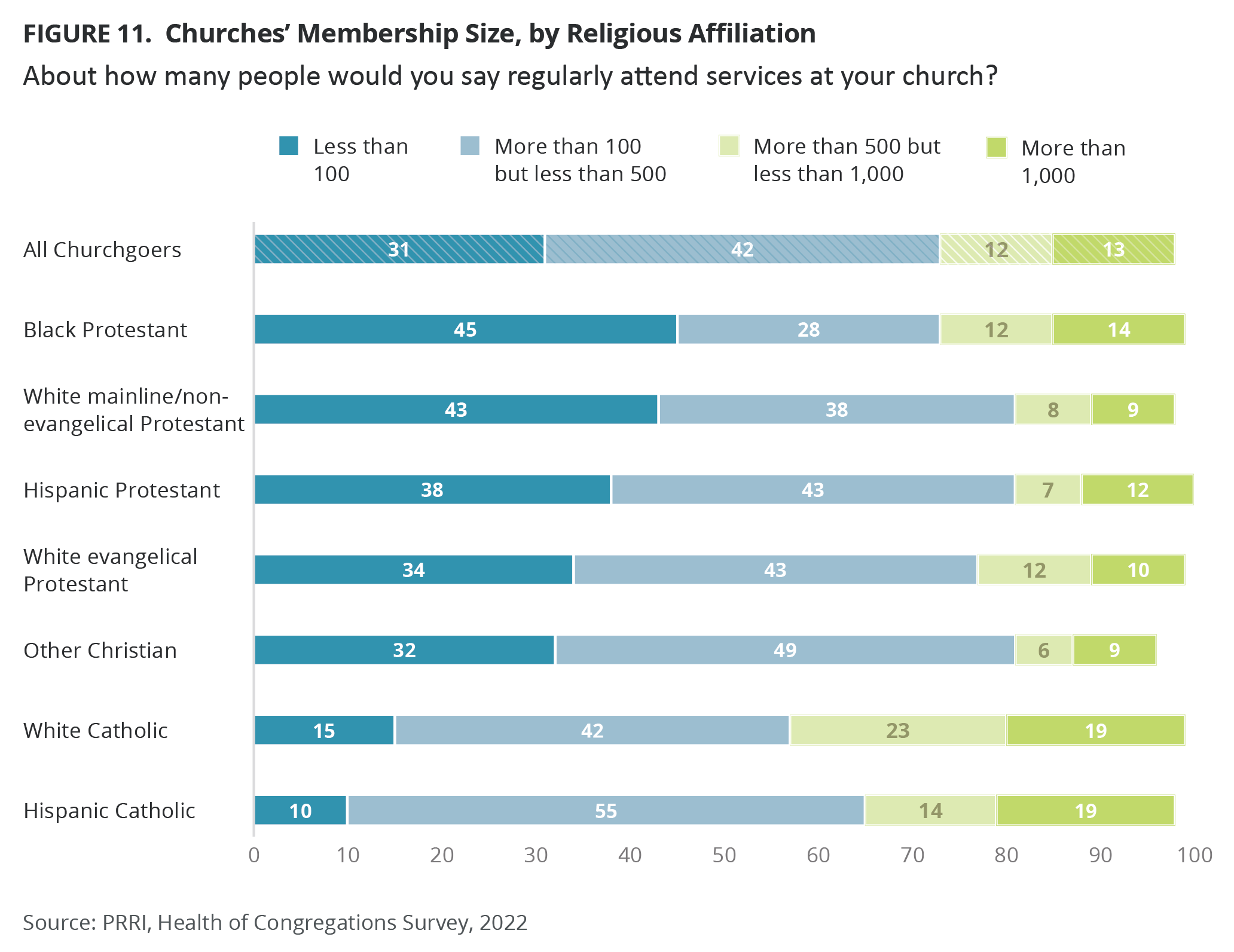

Membership size

Among those who attend religious services at least a few times a year, the vast majority belong to congregations of less than 500 people. About three in ten churchgoers (31%) say less than 100 people regularly attend services at their church, compared with 42% who say more than 100 but less than 500 attend. Only about a quarter of Americans attend churches with congregations of between 500 and 1,000 (12%) or more than 1,000 (13%).

Majorities across religious groups say less than 500 people regularly attend services at their church. This includes 81% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, 81% of Hispanic Protestants, 81% of other Christians, 77% of white evangelical Protestants, 73% of Black Protestants, 65% of Hispanic Catholics, and 57% of white Catholics. By contrast, only a plurality of Catholics as a whole (38%) say more than 500 or 1,000 people attend regularly services at their church, and less than three in ten say this is the case in all other religious groups, including Black Protestants (26%), white evangelical Protestants (22%), Hispanic Protestants (19%), white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (17%), and other Christians (15%).

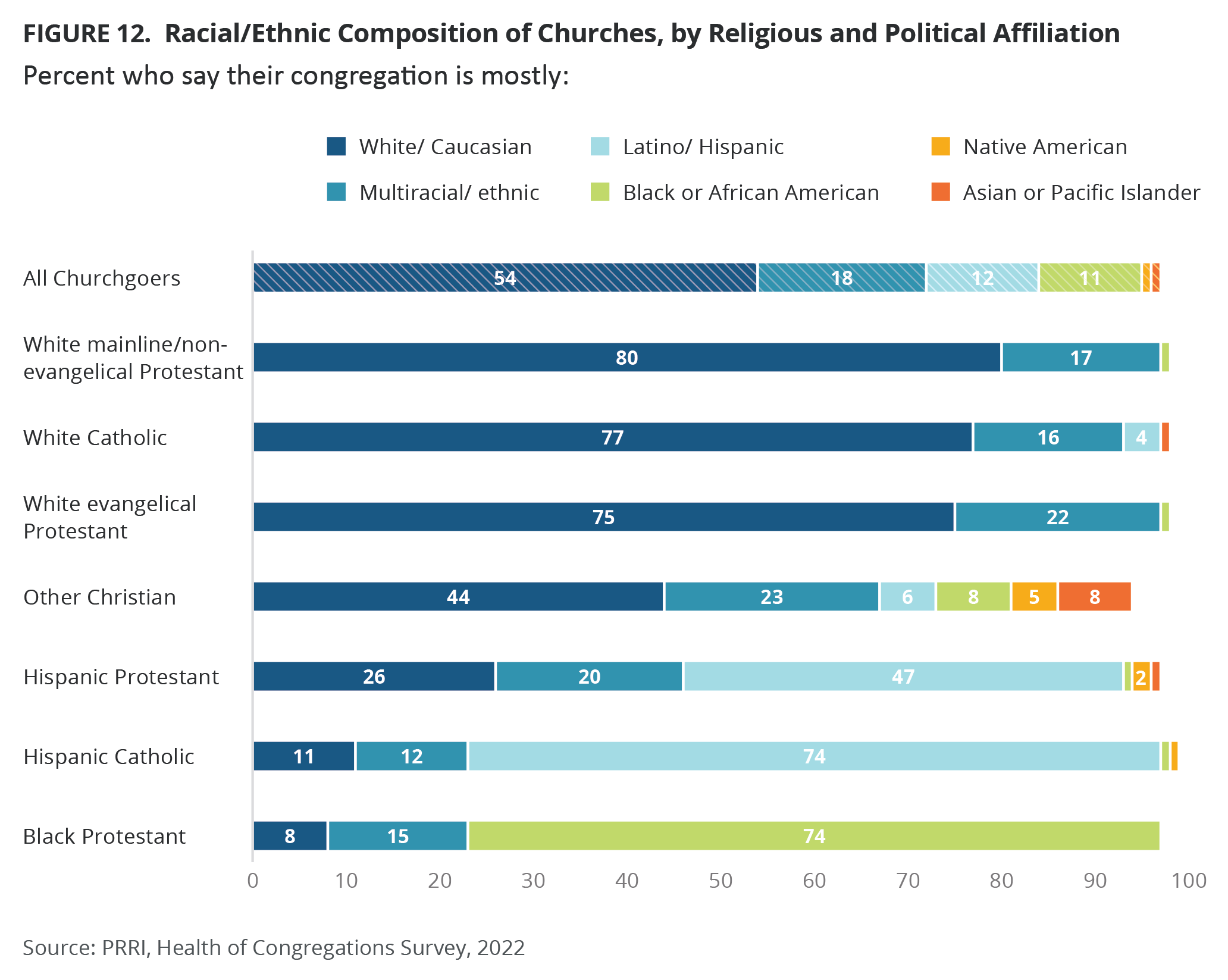

Racial/Ethnic composition of current church

Despite the increasing racial and ethnic diversity of the country, the vast majority of churchgoers report that their congregations are mostly monoracial.

At least three-quarters of white Christians say that their churches are mostly white, including 80% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, 77% of white Catholics, and 75% of white evangelical Protestants. Among these groups, about two in ten say their churches are multiracial (17%, 16%, and 22%, respectively), and 5% or less say their churches have mostly Hispanic, Black, or Asian or Pacific Islander (AAPI) members.

Among Protestants of color, nearly half of Hispanic Protestants (47%) say that their churches are composed mostly of Hispanics, 26% say their churches have mostly white members, 20% attended mostly multiracial congregations, and 4% go to churches with mostly Native American, Black, or APPI members. Among Black Protestants, the vast majority (74%) say their churches have mostly Black members, 15% attend multiracial congregations, and just 8% go to majority-white churches. Nearly three in four Hispanic Catholics (74%) say that their church is mostly Hispanic, 12% attend mostly multiracial churches, 11% go to mostly white churches, and just 2% attend churches that are mostly either Black or Native American.

Experiences at Their Churches

Topics of Discussion Among Clergy

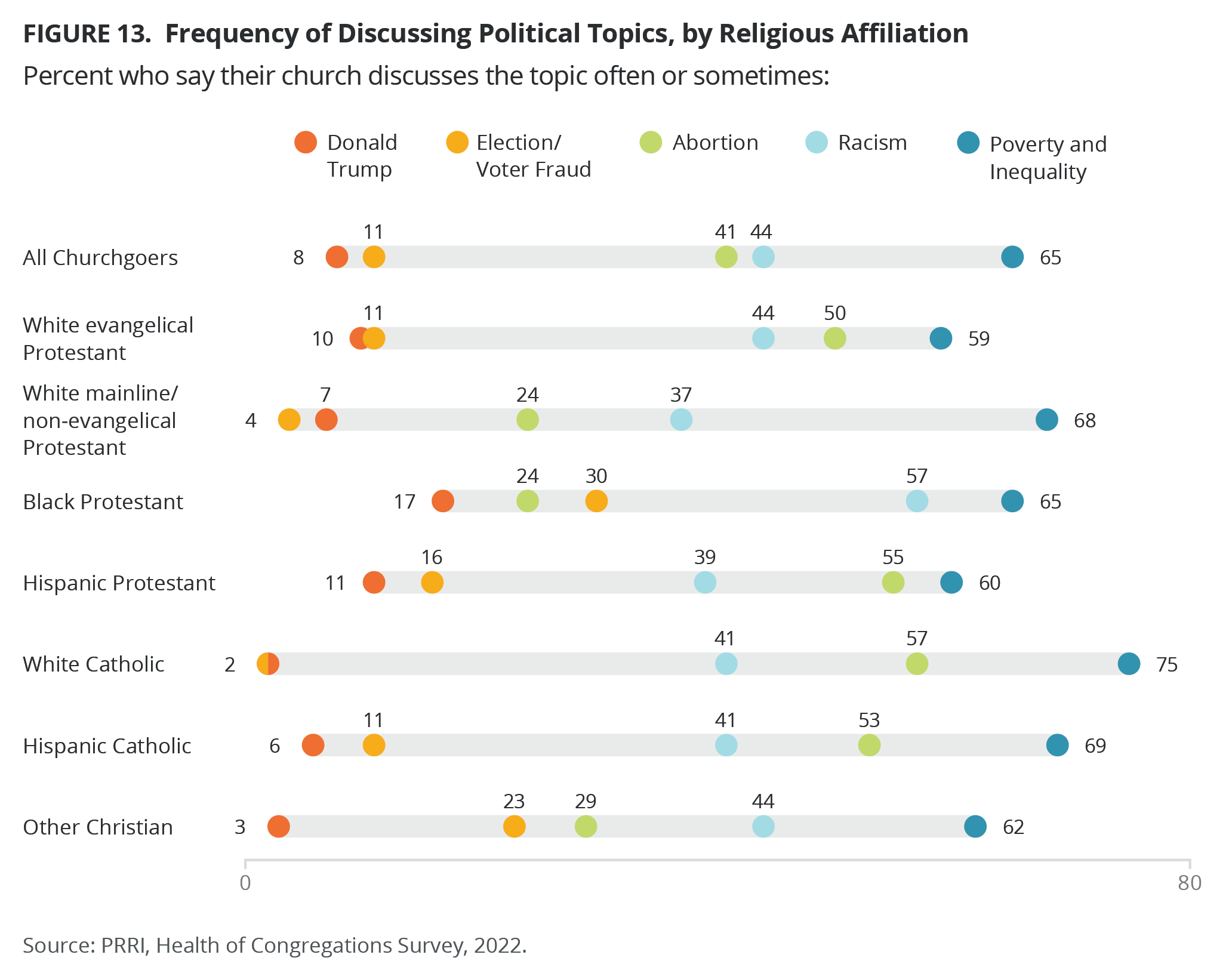

To better understand the dynamics of political conversations in churches, PRRI asked how frequently congregations discuss the following topics in their church: abortion, Donald Trump, election and voter fraud, racism, and poverty and inequality. Only around one in ten churchgoers say their church sometimes or often discusses Donald Trump or election and voter fraud (8% and 11%, respectively). By contrast, around four in ten churchgoers (41%) say abortion is sometimes or often talked about, and 44% say the same about racism. Nearly two-thirds of churchgoers (65%) say their clergy sometimes or often discuss poverty and inequality.

Abortion and poverty and inequality are the topics on which there are significant differences between Christian denominations. Majorities of white Catholics, Hispanic Protestants, and Hispanic Catholics say their clergy talk about abortion sometimes or often (57%, 55%, and 53%, respectively), and half of white evangelical Protestants (50%) say the same. Far fewer other Christians (29%), white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (24%), and Black Protestants (24%) say abortion is sometimes or often discussed in their church. Most churchgoers report having discussions about poverty and inequality in their congregations. This is the case for 59% of white evangelical Protestants, 60% of Hispanic Protestants, 62% of other Christians, 65% of Black Protestants, 68% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, 69% of Hispanic Catholics, and 75% of white Catholics.

Churchgoers from different Christian denominations similarly align on how frequently they hear their clergy discuss the other issues. Black Protestants are the most likely to indicate that their clergy sometimes or often discuss the topic of election and voter fraud (30%), which is higher than the percentage of Hispanic Protestants (16%). Around one in ten or less of the other denominations report their clergy mentioning this topic (11% of white evangelical Protestants and Hispanic Catholics, 4% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, and 2% of white Catholics). Less than two in ten of all groups say they sometimes or often hear their clergy talk about Donald Trump. This is the case for 17% of Black Protestants, 11% of Hispanic Protestants, 10% of white evangelical Protestants, 7% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, 6% of Hispanic Catholics, 3% of Other Christians, and 2% of white Catholics.

The majority of Black Protestants (57%) say their clergy sometimes or often discuss racism, compared with 44% each of white evangelical Protestants and other Christians. Around four in ten white Catholics (41%), Hispanic Catholics (41%), Hispanic Protestants (39%), and white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (37%) say their clergy discuss racism sometimes or often.

Discussions on Difficult Issues

PRRI asked how well American Christians feel their church discusses five difficult issues: racial justice, discrimination against LGBTQ people, hatred toward immigrants, white supremacy, and abortion. More than three-fourths of churchgoers say their church does somewhat or very well discussing racial justice and hatred toward immigrants (77% and 76%, respectively). Around two-thirds say their church talks somewhat or very well about abortion (71%), white supremacy (67%), and discrimination against LGBTQ people (65%).

The vast majority of Republican churchgoers say their church discusses all these issues well. Around three-fourths say their church discusses white supremacy and discrimination against LGBTQ people well (76% and 75%, respectively), and more than eight in ten say the same about abortion (83%), racial justice (81%), and hatred of immigrants (81%). Independent and Democratic churchgoers are both less likely than Republican churchgoers to say that these issues are discussed well in their churches. Among independent churchgoers, 61% say their church discusses discrimination against LGBTQ people well and 76% say their church discusses racial justice well. Two-thirds or more of independents believe their church does a good job talking about white supremacy (67%), abortion (66%), and hatred toward immigrants (77%). Aside from the issue of racial justice, where 73% say their church discusses it well, Democratic churchgoers are less likely than Republican and independent churchgoers to say their church does a good job discussing these difficult topics, including white supremacy (53%), discrimination against LGBTQ people (57%), abortion (60%), and hatred toward immigrants (70%).

White evangelical Protestants are more likely than both white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants and Protestants of color to say their church does well at discussing these different difficult issues. Three in four or more white evangelical Protestants believe their church does a good job of talking about discrimination against LGBTQ people (74%), white supremacy (75%), hatred toward immigrants and abortion (81%), and racial justice (82%). Between two-thirds and three-fourths of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants say their church does well discussing racial justice (77%), hatred toward immigrants (75%), white supremacy (68%), discrimination against LGBTQ people (66%), and abortion (66%) . Solid majorities of Protestants of color, including Black and Hispanic Protestants, say their church discusses hard topics well (62% and 64% for abortion, 63% and 67% for white supremacy, 64% and 71% for hatred toward immigrants, 65% and 59% for discrimination against LGBTQ people, and 75% and 70% for racial justice). For the majority of issues, white Catholics are more likely to think their church does well at discussions than Hispanic Catholics (81% vs. 70% on hatred of immigrants, 76% vs. 70% on racial justice, 71% vs. 67% on abortion, and 65% vs. 52% on white supremacy). Hispanic Catholics are similarly more likely than white Catholics to say their church does well discussing discrimination against LGBTQ people (59% vs. 56%, respectively). Among other Christians, two-thirds say the church discusses discrimination against LGBTQ people and white supremacy well (66%), more seven in ten say the same of abortion (72%), and eight in ten say their church does a good job discussing hatred toward immigrants (80%) and racial justice (80%).

Changes Within the Church

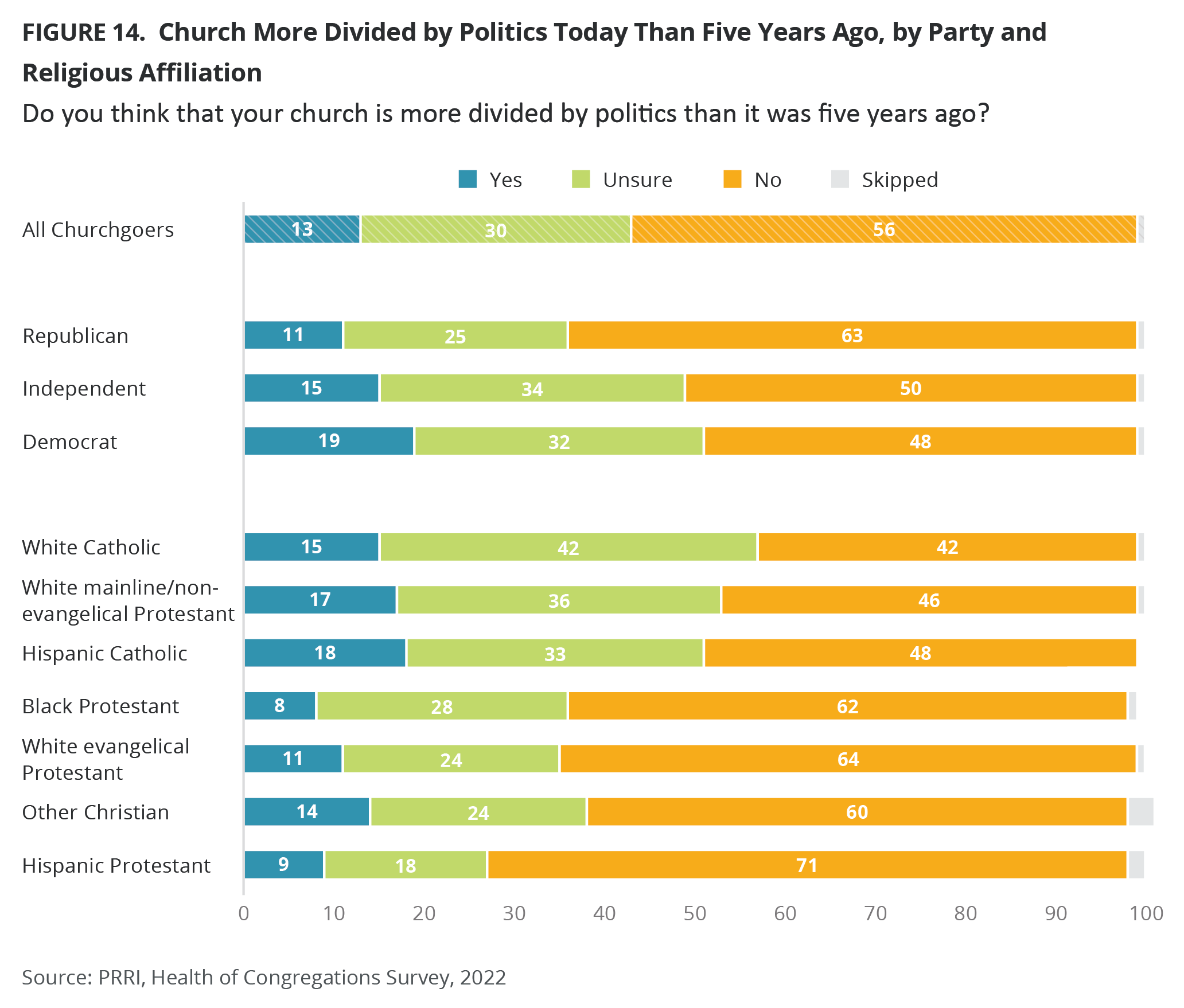

A majority of churchgoers (56%) do not believe their church is more divided by politics than it was five years ago. Only 13% say that their church is more politically divided than it was five years ago.

Republican churchgoers are more likely than independent and Democrat churchgoers to say their church is not more divided by politics than in the past (63% vs. 50% and 48%, respectively). Hispanic Protestants (71%), white evangelical Protestants (64%), Black Protestants (62%), and other Christians (60%) are the groups most likely to say that their church is not more politically divided than in the past. By contrast, less than half of Hispanic Catholics (48%), white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (46%), and white Catholics (42%) say that their church is not more politically divided than it was five years ago.

Churchgoers are more split on whether they believe their church is more racially diverse than it was ten years ago (36% say yes and 34% say no). Around four in ten Republican and independent churchgoers (40% and 42%, respectively) and three in ten Democrat churchgoers (29%) say their church is more racially diverse now than it was a decade ago. Across all Christian denominations, less than half of churchgoers believe their church is now more racially diverse (45% of white Catholics, 41% of other Christians, 37% of Hispanic Protestants, 36% of white evangelical Protestants, 31% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants and Hispanic Catholics, and 29% of Black Protestants).

Is Their Church Welcoming to All?

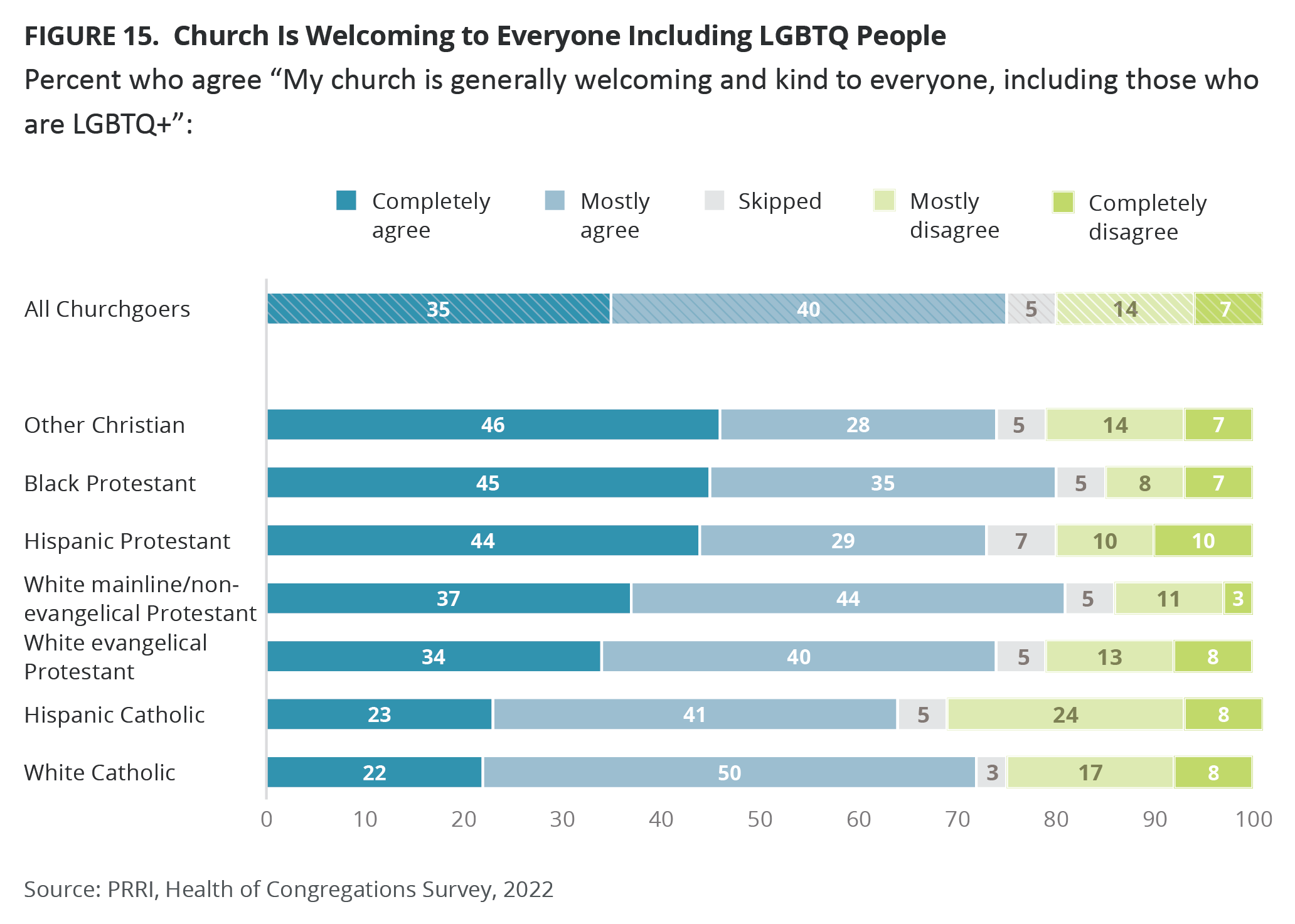

Three in four churchgoers (75%) agree that their church is welcoming to everyone, including LGBTQ people. Hispanic Catholics (64%) are the least likely to agree with this, while 72% of white Catholics, 73% of Hispanic Protestants, 74% of other Christians and of white evangelical Protestants, 80% of Black Protestants, and 81% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants agree. Churchgoers ages 18 to–29 are slightly less likely than churchgoers of other age groups to believe their church is welcoming to all (68% vs. 74% of churchgoers 30–49 and 50–64 and 79% of churchgoers 65 and over).

Slightly less than half of churchgoers (48%) agree with the statement “I would prefer to attend a church that does not discuss gender and sexuality issues.” More than half of white Catholics (59%), Hispanic Catholics (53%), and white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (52%) agree with this statement, as do 47% of other Christians, 45% of white evangelical Protestants, 37% of Black Protestants, and 33% of Hispanic Protestants.

The Church’s Role on Social Issues

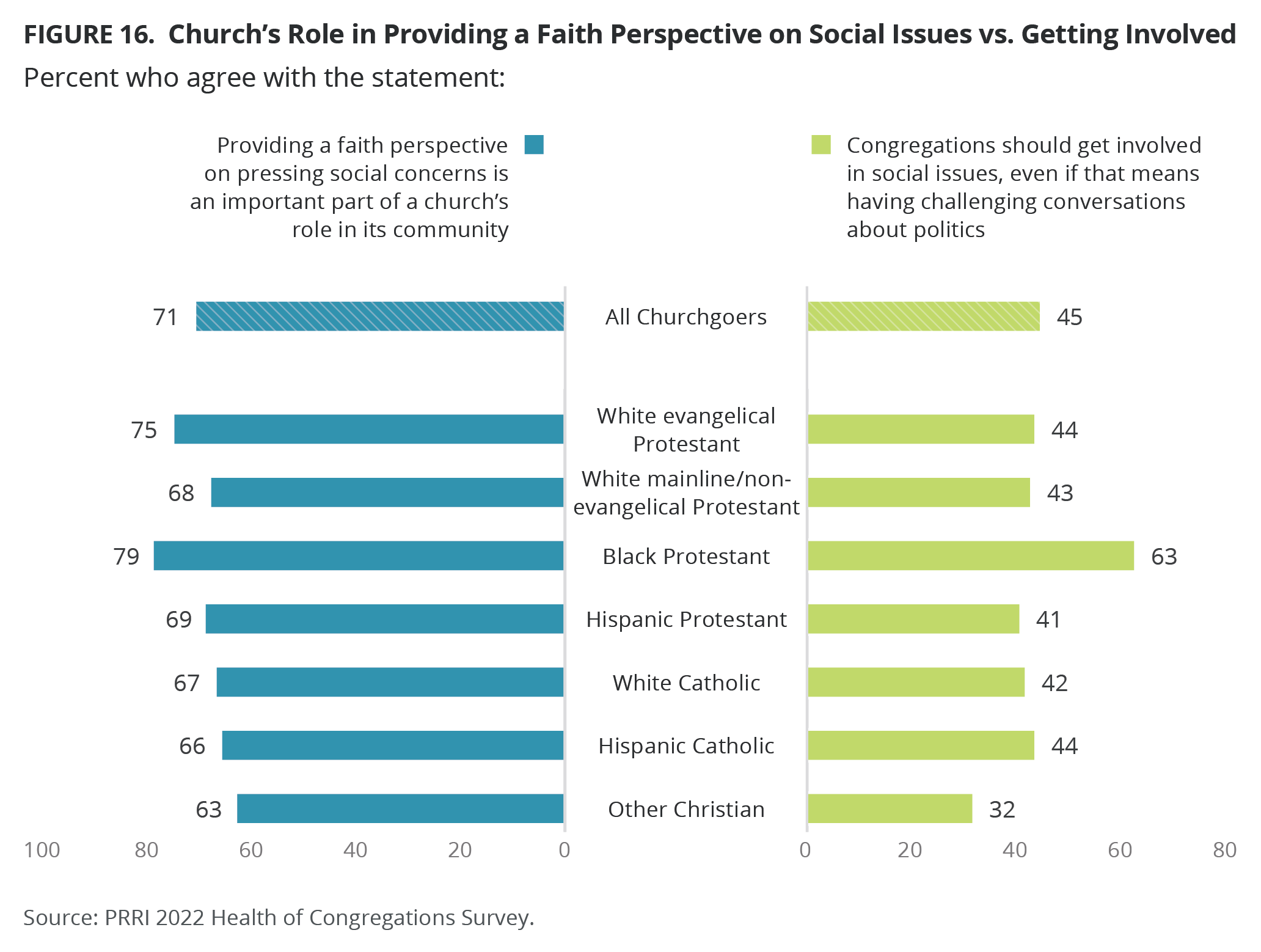

Around seven in ten churchgoers (71%) agree with the statement “Providing a faith perspective on pressing social concerns is an important part of a church’s role.” Churchgoers of all political affiliations have similar rates of agreement with this statement (74% among Democrats, 72% among Republicans, and 68% among independents).

Majorities of all Christian denominations believe that it’s important for churches to provide perspective on social issues, including 79% of Black Protestants, 75% of white evangelical Protestants, 69% of Hispanic Protestants, 68% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, 67% of white Catholics, 66% of Hispanic Catholics, and 63% of other Christians. Two-thirds or more of all age groups agree, but younger churchgoers are less likely than older ones to say this is important, with 66% of those 18–29 agreeing, compared to 74% of those 30–49, 69% of those 50–64, and 70% of those 65 and older.

Despite most churchgoers agreeing that the church should provide perspectives on social issues, less than half (45%) agree with the statement “Congregations should get involved in social issues, even if that means having challenging conversations about politics.” Democratic churchgoers (56%) are more likely than Republican (40%) and independent churchgoers (43%) to agree that churches should get involved in social issues. Black Protestants are the only Christian group in which a majority believe that congregations should get involved (63%). Among other groups, 44% of white evangelical Protestants and of Hispanic Catholics, 43% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, 42% of white Catholics, 41% of Hispanic Protestants, and 32% of other Christians agree with the statement.

The Financial Health of Their Church

One-third of churchgoers (34%) say that their church is better off financially than other churches. Republican churchgoers (38%) are notably more likely than Democratic (33%) and independent (33%) churchgoers to say their church is better off financially than other churches.

No Christian group reaches a majority who say that their church is better off financially than other churches, with 40% of other Christians, 38% of white Catholics, 36% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, 33% of white evangelical Protestants, 32% of Hispanic Protestants, 30% of Black Protestants, and 26% of Hispanic Catholics saying this is the case.

The Impact of the Pandemic on Their Church

Four in ten churchgoers (39%) believe that church relationships have been strained because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The same percentage of Republican and independent churchgoers (both 39%) and less than half of Democrats (46%) say that relationships in their church have been negatively affected by the pandemic.

Less than half of all Christian groups believe the pandemic has strained church relationships (48% of white Catholics, 43% of white mainline Protestants, 40% of Protestants of color, 38% of Hispanic Catholics, 37% of white evangelical Protestants, and 28% of other Christians).

Churchgoers in the 50–64 age range (44%) and 65 and up (44%) are more likely to say their relationships in church have been strained by the pandemic than churchgoers ages 18–29 (34%) and 30–49 (32%).

Optimism About the Future of Their Church

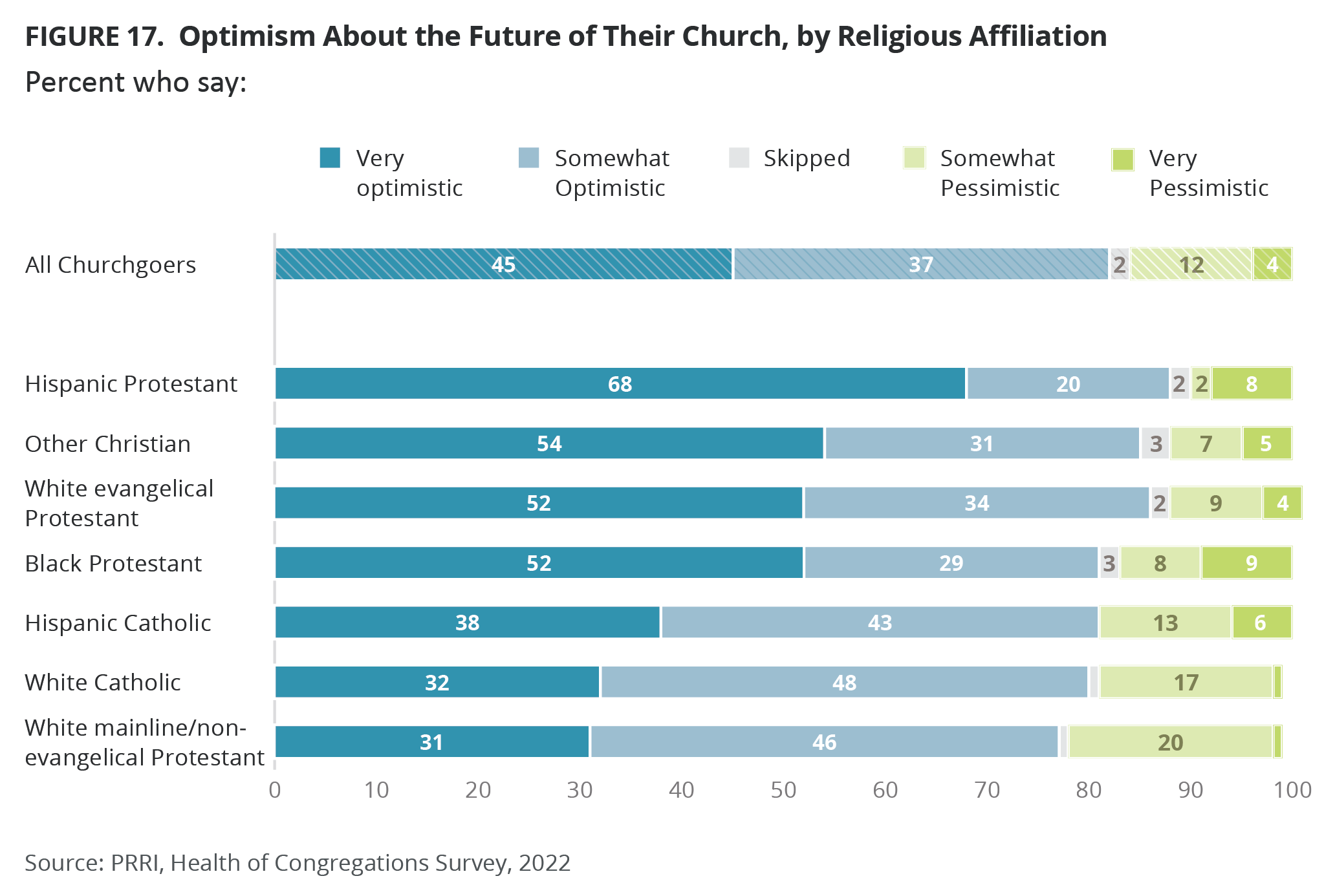

More than eight in ten churchgoers (82%) say they are optimistic about the future of their church. The rate of optimism is similar across the Christian denominations (88% among Hispanic Protestants, 86% among white evangelical Protestants, 85% among other Christians, 81% among Black Protestants, 81% among Hispanic Catholics, 80% among white Catholics, and 77% among white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants). However, majorities of Hispanic Protestants (68%), other Christians (54%), and both white evangelical Protestants and Black Protestants (52% each) say they are very optimistic about the future of their church, while around four in ten Hispanic Catholics (38%) and three in ten white Catholics and white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (32% and 31%, respectively) have the same sentiment.

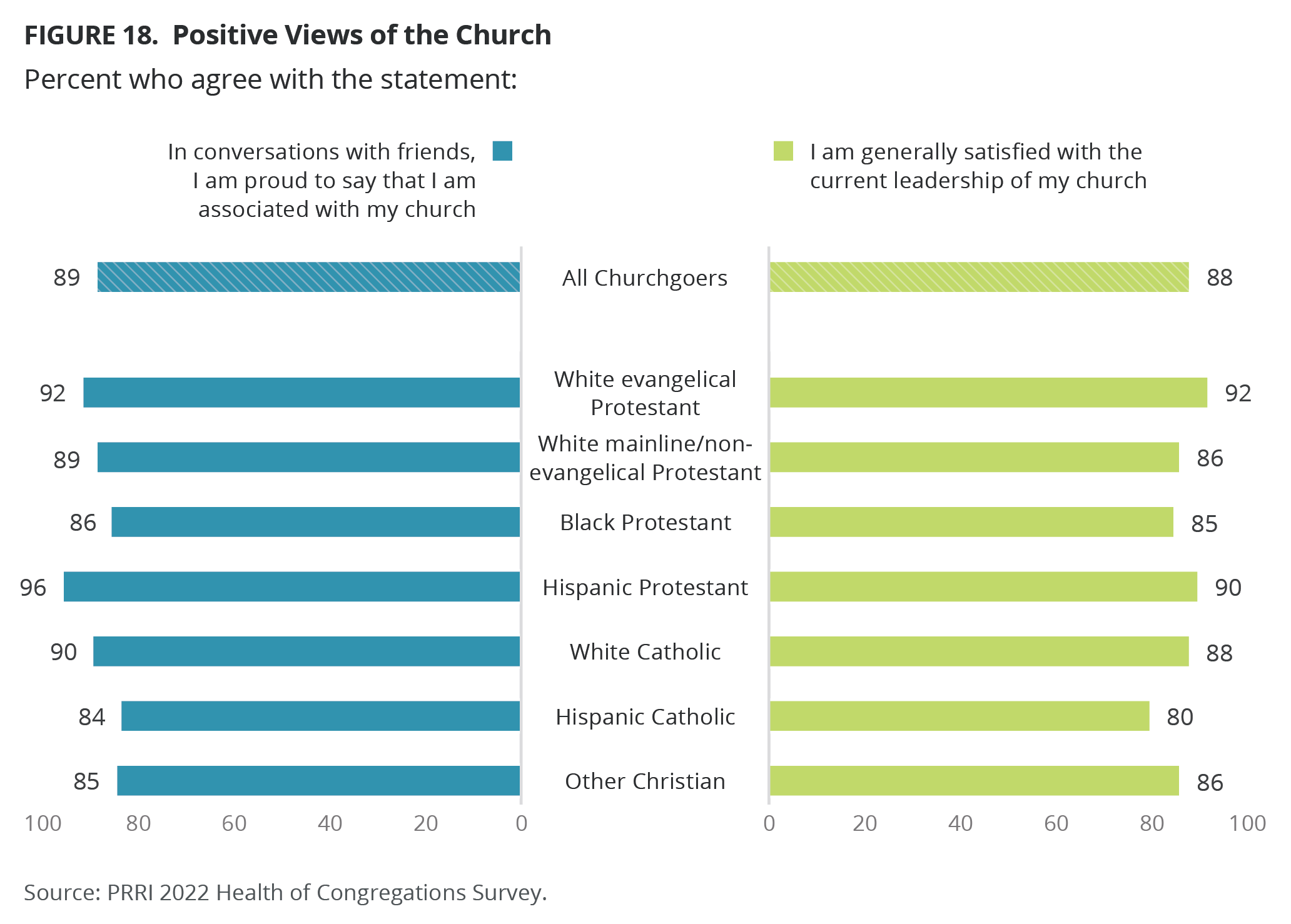

Nearly nine in ten churchgoers (89%) agree with the statement “In conversations with my friends, I am proud to say that I am associated with my church.” This includes more than half who say they completely agree (53%). The vast majority of churchgoers in all Christian religious traditions agree that they are proud to be associated to their church (96% of Hispanic Protestants, 92% of white evangelical Protestants, 90% of white Catholics, 89% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, 86% of Black Protestants, 85% of other Christians, and 84% of Hispanic Catholics). Majorities of Hispanic Protestants (66%), white evangelical Protestants (61%), Black Protestants (60%) and other Christians (55%) say they completely agree. The percentage of those who completely agree is somewhat lower among white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (46%), white Catholics (44%), and Hispanic Catholics (37%).

Similarly, around nine in ten churchgoers (88%) agree with the statement “I am generally satisfied with the current leadership of my church.” Large majorities of each denomination say this is true, including 92% of white evangelical Protestants, 90% of Hispanic Protestants, 88% of white Catholics, 86% of other Christians, 86% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, 85% of Black Protestants, and 80% of Hispanic Catholics. Majorities of Hispanic Protestants (58%), other Christians (54%), white evangelical Protestants (53%), and Black Protestants (53%) say they completely agree that they are satisfied with the leadership in their congregation, while minorities of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (42%), Hispanic Catholics (32%), and white Catholics (29%,) say the same.

Diversifying Churches and Congregations

Diversifying Church Leadership

People of Color in Leadership

Among white churchgoers, white evangelical Protestants (36%) are less likely than white Catholics (46%) or white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (48%) to express a desire to have more people of color in their church’s leadership. Hispanic Catholics are notably the only group in which a majority (56%) wish there were more people of color in church leadership.

A slight majority of young white churchgoers ages 18–29 (52%) say they wish their church had more people of color in leadership, compared with four in ten white churchgoers ages 30–49 (41%), ages 50–64 (39%), and over age 65 (40%).

Women in Leadership

Just under four in ten churchgoers (37%) say they wish their church had more women in positions of leadership, while 59% say they do not. White evangelical Protestants (25%) are the least likely to express a desire for more women in leadership, compared with 33% of other Christians, 35% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, 37% of Hispanic Protestants, 42% of Black Protestants, and 44% of white Catholics. Again, Hispanic Catholics stand out: 64% want more women in their church leadership.

Younger churchgoers ages 18–29 (43%) and ages 30–49 (42%) are slightly more likely than those ages 50–64 (35%) and over age 65 (32%) to wish there were more women in their church’s leadership.

LGBTQ People in Leadership

Roughly one in five churchgoers (21%) agree that they wish there were more LGBTQ people in their church’s leadership, while 72% disagree. Religious groups are particularly divided over the issue of LGBTQ leadership in their church. Roughly one in ten white evangelical Protestants (10%) and Hispanic Protestants (13%) wish their church had more LGBTQ people in leadership. Higher percentages of other Christians (21%), Black Protestants (23%), white Catholics (25%), white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (30%), and Hispanic Catholics (39%) wish their church had more LGBTQ leaders.

Churchgoers are politically divided over wanting more LGBTQ people in their church’s leadership. Less than one in ten Republican churchgoers (9%) want more LGBTQ church leaders, compared to 23% of independent churchgoers and 39% of Democratic churchgoers.

Young churchgoers ages 18–29 are the age group most likely to express a desire for more LGBTQ church leaders (33%), compared to 22% of churchgoers ages 30–49, 21% of churchgoers ages 50–64, and 17% of churchgoers age 65 and over.

What Can the Church Talk More About?

Addressing Political Divisions

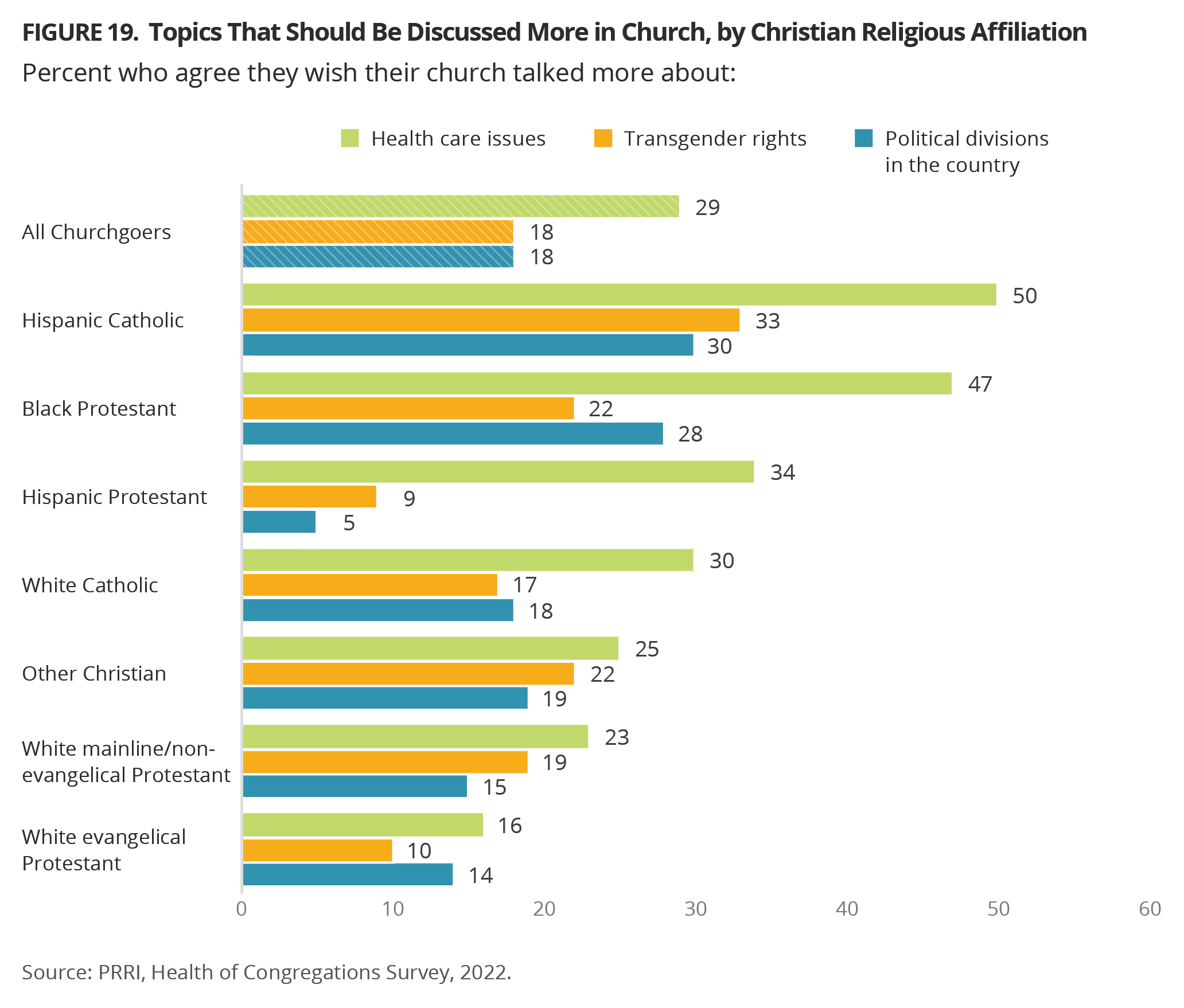

Fewer than two in ten churchgoers (18%) agree that they wish their church talked more about political divisions in the country, while 77% disagree. Christians of color (24%) are slightly more likely than white Christians (16%) to say that they wish their church addressed political divisions more.

About three in ten Black Protestants (28%) and Hispanic Catholics (30%) say they wish their church talked more about political divisions. A smaller percentage other Christians (19%), white Catholics (18%), white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (15%), white evangelical Protestants (14%), and Hispanic Protestants (5%) say the same.

Republican (13%) and independent (17%) churchgoers are somewhat less likely than Democratic churchgoers (29%) to say they wish their church talked more about political divisions.

Young churchgoers ages 18–29 (28%) are the most likely to say they wish their church talked more about political divisions, compared with 19% of churchgoers ages 30–49, 17% of churchgoers ages 50–64, and 15% of churchgoers over age 65.

Addressing Health Care Issues

Around one in three churchgoers (29%) agree that they wished their church talked more about health care–related issues, while 67% disagree. Christians of color (42%) are almost twice as likely as white Christians (22%) to wish their church talked more about health care.

Around half of Hispanic Catholics (50%) and Black Protestants (47%) say they wish their church talked more about health care issues, compared with around a third of Hispanic Protestants (34%) and white Catholics (30%). About one in four white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (23%) and other Christians (25%), and less than two in ten white evangelical Protestants (16%), agree.

There are only minimal differences across age groups in the desire for churches to talk about health care issues. Young churchgoers ages 18–29 (34%) are slightly more likely than those ages 30–49 (29%), 50–64 (29%), and 65 and over (27%) to say they wish their church talked more about health care issues.

Addressing Transgender Rights

Fewer than two in ten churchgoers (18%) agree that they wish their church talked more about transgender rights, while 78% disagree. White Christians (14%) are about half as likely as Christians of color (26%) to say they wish their church talked more about transgender rights.

One-third of Hispanic Catholics (33%) wish their church had more discussion of transgender rights. Around two in ten Black Protestants (22%), other Christians (22%), white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (19%), and white Catholics (17%) say the same, as do one in ten white evangelical Protestants (10%) and Hispanic Protestants (9%).

Young churchgoers ages 18–29 (30%) are more likely than those ages 30–49 (18%), 50–64 (15%), and 65 and over (14%) to say they wish their church talked more about transgender rights.

Working with Other Churches

Around half of churchgoers (48%) agree that they wish their church worked more with other churches, while another 48% disagree. Just over four in ten white Christians (43%) agree, compared to nearly six in ten Christians of color (58%).

Hispanic Protestants (62%), Hispanic Catholics (61%), and Black Protestants (58%) are the most likely to agree that they wish their church worked more with other churches, compared to half of white Catholics (49%) and about four in ten other Christians (43%), white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (43%), and white evangelical Protestants (40%).

Differences between age groups on this measure are small. Among churchgoers ages 18–29, 43% wish their church worked more with other churches, compared to a majority of churchgoers ages 30–49 (52%), half of those ages 50–64 (49%), and 46% of those over age 65.

Better Programming for Children

Around four in ten churchgoers (41%) agree that they wish their church had better children’s programming, while a majority disagree (55%). Three in ten regular churchgoers have children under the age of 18, and around half of Christian parents (47%), compared to a somewhat smaller share of churchgoers who do not currently have children (38%) wish for better church programming for children. A majority of Christians of color (52%), compared to 35% of white Christians, wish their church had better children’s programming.

Hispanic Catholics (63%), Hispanic Protestants (54%), and Black Protestants (50%) are the most likely to agree they want better children’s programming in their church. About four in ten white Catholics (45%) and white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (39%) agree, compared to around three in ten other Christians (29%) and white evangelical Protestants (31%).

Among churchgoers ages 30–49 (who are the age group most likely to have children under age 18), 46% wish for better children’s programming, as do 41% of those ages 50–64. The numbers are slightly lower among those ages 18–29 and those 65 and over (38% for both groups).

Religious Pluralism vs. Christian Nationalism

America Losing Identity

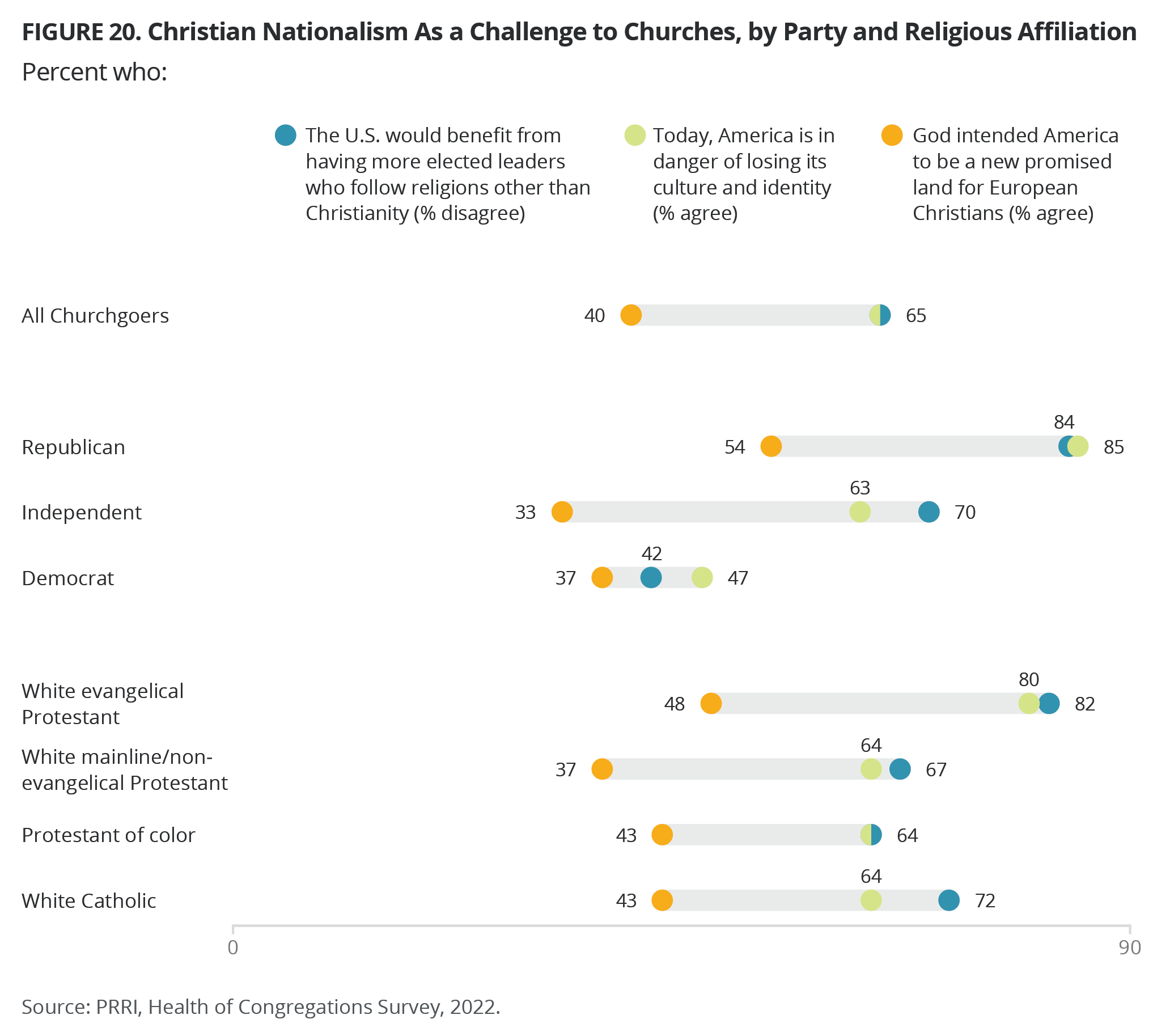

Two-thirds of churchgoers (65%) agree with the statement “Today, America is in danger of losing its culture and identity,” compared with 34% who disagree. Republican churchgoers (85%) are nearly twice as likely as Democratic churchgoers (47%) to agree with this statement. Independent churchgoers (63%) fall in between.

While majorities of churchgoers agree that America is in danger of losing its culture and identity, white evangelical Protestants are more likely to agree (80%) than white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, Protestants of color, and white Catholics (64% each).[13]

Young churchgoers are slightly less likely to agree with the idea that America is in danger of losing its culture and identity, with 57% of churchgoers ages 18–29 saying this is the case, compared with 65% of both churchgoers ages 30–49 and ages 50–64, and 68% of senior churchgoers ages 65 and over.[14]

God Intended America to Be a New Promised Land

Four in ten churchgoers (40%) agree with the statement “God intended America to be a new promised land where European Christians could create a society that could be an example to the rest of the world,” and 55% disagree. A majority of Republican churchgoers (54%) agree with this statement, compared with about one-third of independent (33%) and Democrat (37%) churchgoers.

Nearly half of white evangelical Protestants (48%) completely or mostly agree that God intended America to be a new promised land for European Christians, compared with 43% of both Protestants of color and white Catholics and 37% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants.

About four in ten churchgoers ages 30–49 (38%), 43% of churchgoers ages 50–64, and 45% of senior churchgoers ages 65 and over also agree that God intended America to be a new promised land.[15]

U.S. Would Benefit From Having More Elected Leaders Who Follow Religions Other Than Christianity

About three in ten churchgoers (32%) agree with the statement “The U.S. would benefit from having more elected leaders who follow religions other than Christianity or are not religious at all,” and two-thirds (65%) disagree. Republican churchgoers (84%) are twice as likely as Democratic churchgoers (42%) to disagree with this idea. The majority of independent churchgoers (70%) also disagree.

Among the different groups of Christian churchgoers, unsurprisingly, white evangelical Protestants (82%) are the most likely to disagree with the idea that the U.S. would benefit from having elected leaders who follow other religions or are nonreligious, while 72% of white Catholics, and about two-thirds each of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (67%) and Protestants of color (64%) also disagree.

Disagreement with the idea that the U.S. would benefit from having more elected leaders who follow religions other than Christianity increases with age: nearly half of young churchgoers ages 18–29 (48%) disagree, compared with 61% of churchgoers ages 30–49, 67% of churchgoers ages 50–64, and 76% of senior churchgoers ages 65 and over.[16]

Survey Methodology

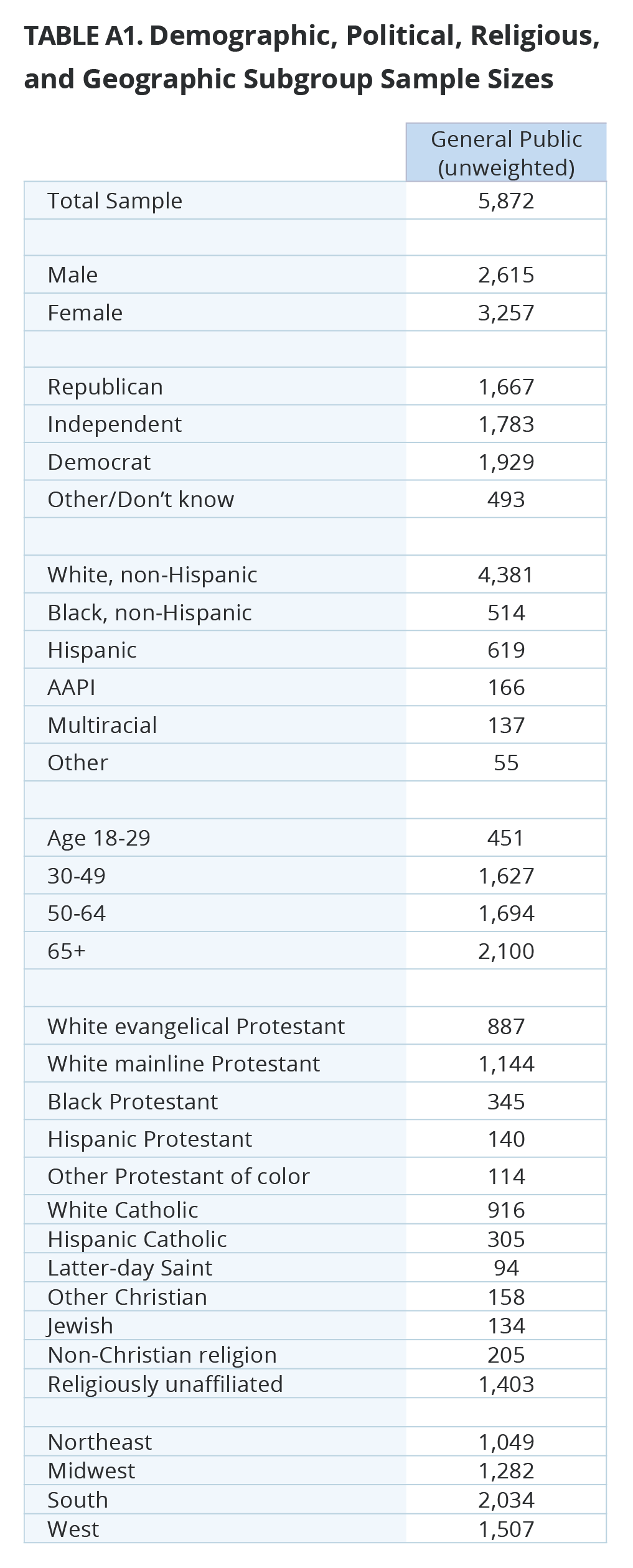

The survey was designed and conducted by PRRI. The survey was made possible through the generous support of the Duke Endowment. The survey was conducted among a representative sample of 5,872 adults (age 18 and up) living in all 50 states in the United States, who are part of Ipsos’s Knowledge Panel and an additional 536 who were recruited by Ipsos using opt-in survey panels to increase the sample sizes in smaller states. Additionally, this survey includes 212 additional respondents recruited by Ipsos using opt-in survey panels to increase the number of white mainline Protestants in the data. Interviews were conducted online between August 9 and August 30, 2022.

The survey was designed and conducted by PRRI. The survey was made possible through the generous support of the Duke Endowment. The survey was conducted among a representative sample of 5,872 adults (age 18 and up) living in all 50 states in the United States, who are part of Ipsos’s Knowledge Panel and an additional 536 who were recruited by Ipsos using opt-in survey panels to increase the sample sizes in smaller states. Additionally, this survey includes 212 additional respondents recruited by Ipsos using opt-in survey panels to increase the number of white mainline Protestants in the data. Interviews were conducted online between August 9 and August 30, 2022.

Respondents are recruited to the KnowledgePanel using an addressed-based sampling methodology from the Delivery Sequence File of the USPS – a database with full coverage of all delivery addresses in the U.S. As such, it covers all households regardless of their phone status, providing a representative online sample. Unlike opt-in panels, households are not permitted to “self-select” into the panel; and are generally limited to how many surveys they can take within a given time period.

The initial sample drawn from the KnowledgePanel was adjusted using pre-stratification weights so that it approximates the adult U.S. population defined by the latest March supplement of the Current Population Survey. Next, a probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling scheme was used to select a representative sample.

To reduce the effects of any non-response bias, a post-stratification adjustment was applied based on demographic distributions from the most recent American Community Survey (ACS). The post-stratification weight rebalanced the sample based on the following benchmarks: age, race and ethnicity, gender, Census division, metro area, education, and income. The sample weighting was accomplished using an iterative proportional fitting (IFP) process that simultaneously balances the distributions of all variables. Weights were trimmed to prevent individual interviews from having too much influence on the final results. In addition to an overall national weight, separate weights were computed for each state to ensure that the demographic characteristics of the sample closely approximate the demographic characteristics of the target populations. The state-level post-stratification weights rebalanced the sample based on the following benchmarks: age, race and ethnicity, gender, education, and income.

The margin of error for the national survey is +/- 1.86 percentage points at the 95% level of confidence, including the design effect for the survey of 1.96. In addition to sampling error, surveys may also be subject to error or bias due to question wording, context, and order effects. Additional details about the KnowledgePanel can be found on the Ipsos website: https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/solution/knowledgepanel

Endnotes

[1] Because the number of cases for Latter-day Saints is 94, results need to be interpreted with caution; the group identified as “other Christians” includes other Catholics of color, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Orthodox Christians.

[2] The other non-Christians group includes Muslim, Buddhist, Hindus, Unitarian Universalists, and those who belong to any other world religion.

[3] The number of cases for Hispanic Protestants in 2013 is too small to report (N=76).

[4] Current lower religious attendance numbers are likely due, in part, to the COVID-19 pandemic. https://news.gallup.com/poll/350462/person-religious-service-attendance-rebounding.aspx

[5] Other racial groups include Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, and multiracial Americans.

[6] This includes people who moved between similar denominations within the same religious tradition category.

[7] The category “other Christians” includes Latter-Day Saints, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Greek or Russian Orthodox Christians. Non-Christian religions include Judaism, Buddhism, Unitarianism, Hinduism, and Islam. This survey didn’t ask if respondents previously identified as religiously unaffiliated.

[8] Percentages exclude those who previously identified with their current religion.

[9] Catholics of all races are combined as the number for white and Hispanic Catholics is too small to report on these groups separately, as is the number of Protestant of color.

[10] In 2016, the wording of the question was “Negative religious teachings about or treatment of gay and lesbian people.”

[11] Catholics of all races are combined as the number of cases for white and Hispanic Catholics is too small to report on these groups separately, as is the number of cases for other Christians.

[12] Because the sample size is restricted to Christians who attend services at least a few times a year, the number of cases across some groups was notably reduced. These sections, therefore, combine other Christians as follows: other Protestants of color, other Catholics of color, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Latter-day Saints, and Orthodox Christians. The number of cases for Hispanic Protestants is 97.

[13] Protestants of color include Black Protestants, Hispanic Protestants, and other Protestants of color. The numbers of cases among churchgoers for all other religious groups are too small to report.

[14] Because this question was asked of only half the sample, the number of cases for young churchgoers was reduced to 97.

[15] Because this question was asked of half the sample, the number of cases for young churchgoers is 82, which is too small to report here.

[16] Because this question was asked of half the sample, the number of cases for young churchgoers was reduced to 97.

Recommended Citation

“Religion and Congregations in a Time of Social and Political Upheaval.” PRRI (May 16, 2023). https://www.prri.org/research/religion-and-congregations-in-a-time-of-social-and-political-upheaval/